African Americans in Seattle faced segregation in housing, employment practices, commercial and social establishments, hospitals, schools, and restaurants that was almost as rigid as that of the Jim Crow South. Although Washington State had laws against racial discrimination, they were inadequately enforced. Civil rights activists in Seattle, then, needed to prove the extent of institutionalized discrimination, as well as struggle to change it.

Housing segregation, officially instituted in the early 1900s, confined the majority of Seattle’s African-American community to the neighborhood known as the Central District, located between downtown Seattle and Lake Washington. By the 1960s, the Central District had developed into the heart of civil rights struggle in Seattle, and several organizations were founded in the neighborhood to combat the institutionalized segregation and lack of services.

Earlier civil rights groups, like the municipal Civic Unity Committee, drew together city officials and African-American elites to lobby for small changes. By the early 1960s, however, the civil rights community in Seattle began to combine these lobbying and legislative tactics with large-scale campaigns that involved grassroots organizing and the direct action tactics being popularized in the south. The Central Area Civil Rights Committee (CACRC), founded in 1961, drew together the Seattle-area leadership of longstanding organizations like the NAACP, the Urban League, and the newly-formed Seattle Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chapter into a united force that could mobilize around specific campaigns.

The leaders of CACRC were drawn from the elite of Seattle’s African-American community, and its most prominent members were First AME Church minister Reverend John H. Adams; Seattle NAACP President Charles V. Johnson; CORE Director Walter Hundley; and the Urban League’s Executive Director, Edwin Pratt. The combined membership of CACRC’s groups reached almost 3,000, and pulled many more supporters into their orbit.

One of the most active groups within Seattle’s CACRC was the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, a local chapter of the national organization founded in 1942 to employ non-violent direct action tactics to combat segregation in the South. Inspired by CORE’s freedom rides in the South, a CORE chapter was formed in Seattle in 1961. Seattle’s CORE chapter brought the national political strategy to bear in their campaigns for open housing, against employer discrimination, and for education reform in Seattle.

In October 1961, CORE launched a campaign, in conjunction with other CACRC groups, against employment discrimination in the downtown area. Activists alternated formal negotiations with boycotts, pickets, and direct action techniques like the “shoe-in” or “shop-in,” where protesters filled grocery carts or tried on numerous pairs of shoes and left without buying or taking any items, tying up the stores’ business. Seattle CORE achieved its first boycott victory in 1962, any by 1964 had won more than 250 new jobs for African-Americans in downtown stores. [CORE’s Campaign Against Employment Discrimination in 1960s Seattle]

CORE’s focus on hiring practices culminated in the 1964 Drive for Equal Employment in Downtown Stores, or DEEDS, campaign, intended to use the previous campaign’s victories in individual stores to win policies that would benefit larger layers of black workers. CORE formed research teams to poll downtown businesses to determine the extent of job discrimination, and then used the results to request business owners to change their practices. When their polite queries went unanswered, CORE, in conjunction with CACRC, the NAACP, the Greater Seattle Council of Churches, and other organizations initiated a boycott from October 1964–January 1965. The boycott, however, was not a success, for it had little impact on the downtown Christmas season and garnered scant citywide attention. The failure of the DEEDS campaign, despite initial successes, nearly bankrupted and demoralized the cadre of activists in CORE. [CORE’s Drive for Equal Employment in Downtown Seattle, 1964]

Much of the chapter’s momentum during the period came from their involvement in the open housing campaign. Beginning in the 1950s, Seattle’s civil rights community had advocated for fair, non-discriminatory housing, and by 1962, African-American community leaders led small protests for open housing. In 1963, CORE initiated “Operation Windowshop,” encouraging African-American families to visit open houses and realtors outside of the Central District. When these earlier protests met huge resistance from white neighborhoods and realtors, CORE and much of Seattle’s civil rights movement focused their energies on changing city legislation. Open housing advocates won the creation of the Seattle Human Rights Commission to draft a citywide open housing ordinance, and successfully lobbied the City Council to put it on the ballot for March 10, 1964. The prospect of the ordinance generated a vicious backlash against anti-discrimination activists, who used bombs and cross burnings to harass open housing advocates. [The 1964 Housing Election: How the Press Influenced the Campaign]

Despite a vigorous campaign by CORE and other activists in the city, the measure was defeated. Convinced that legislation and lobbying was not enough, in March 1964, the Seattle chapter launched a picketing campaign against Picture Floor Plans, a large realtor who refused to sell to black buyers. The Picture Floor pickets revealed a shift in CORE’s strategy. Employing more aggressive tactics, activists sang, chanted, heckled, and tried to force their way into the building. When a Picture Floor Plans employee struck a protester, the chapter suspended the pickets altogether. Though this was a minor incident, it revealed a new wave of activists within Seattle CORE and CORE nationally who were becoming frustrated with an adherence to nonviolence and non-retaliation, and moving toward other methods of activism.

President Johnson’s War on Poverty legislation, announced in January of 1964, provided a concrete organizing center for activists frustrated with the losses of the employment and housing campaigns. In anticipation of this legislation, informal discussions between members of the Urban League and the Central Area Community Council led to the formation of the Central Area Citizen’s Committee. When the Economic Opportunity Act was passed that summer, the new organization became the first organization in the country to receive federal funding for anti-poverty initiatives. Renaming themselves CAMP—Central Area Motivation Project—the new community agency focused their work on implementing the federal initiative within the Central District. [Documents from CAMP and the War on Poverty]

The turn toward community organizing and neighborhood empowerment fit with the frustrations of some in CORE and the CACRC who wanted to change not just city laws, but the patterns of unemployment, neighborhood blight, and disempowerment that affected Seattle’s African-American community. Though CAMP often functioned as a city service agency, their ambitions went much further. CAMP sought to be a “motivating” force to bring community members themselves into the struggle against poverty and injustice. One of the most successful programs was the Action Education Center, where staff members and community activists practiced a philosophy of “demythologizing, re-education, and motivation to social action” to bring programs to area schools and stage events to change attitudes around racism and poverty.

By 1967, CAMP was considered the “service arm” of Seattle’s civil rights movement, with a monthly newspaper, The Trumpet , and dozens of service programs. Though CAMP had a paid staff and received federal funds, it also involved many of the Central District’s grassroots activists in its programs, including those who would go on to form the Seattle Black Panther Party. Though CAMP’s funding was cut in the mid-1960s, they were able to form numerous successful campaigns, including the extension of bus service to the Central District, family planning and day care centers, performing arts and tutoring programs, and job services. CAMP is still involved in the same anti-poverty work in Seattle today, and is the oldest surviving agency launched during the era. [Official website of the Central Area Motivation Project]

Meanwhile, CORE and CACRC continued their work. In 1965, the orgranizations publicized police brutality and launched citizens’ “Freedom Patrols” to monitor police activity in the Central District. The following year, they documented school segregation in Seattle and staged a three-day school boycott, opening alternative “freedom schools” that served more than 3,000 boycotting students. [The 1965 Freedom Patrols and the Origins of Seattle’s Police Accountability Movement] [The Seattle School Boycott of 1966]

But by 1968, younger, more militant activists were abandoning the weakened CORE in favor of newly formed organizations like the Black Students’ Union and the Black Panther Party. The CACRC, too, which had presented itself as the voice of Seattle’s African-American community in the early 1960s, realized that they could no longer hold together a coalition of groups that were beginning to develop divergent aims. The differences came to a head in 1968 when the conservative leadership of the CACRC took a stance against black control of schools in the Central District in favor of closing the schools and “forcing integration” by busing black students into other parts of the city. To many residents of the Central District and a new wave of activists, this would disadvantage Central District children and was a single-minded focus on integration as a principle, rather than an emphasis on development and empowerment within Seattle’s black community.

The emphasis on community control in the Central District, realized in different ways by CAMP and the Black Panther Party, inspired the development of new movements in Seattle’s other racially confined communities. Following the examples of the Central District, these group worked to reclaim and revitalize their own neighborhoods. In March of 1970, Native Americans occupied Fort Lawton Army Base in Seattle and claimed it for all “urban Indians.” In the International District, Asian-American activists worked to preserve the ID and expand affordable housing and social services in Seattle’s traditionally Asian community. In 1972, Chicano/a activists reclaimed an abandoned school in the Beacon Hill neighborhood to found El Centro de la Raza community center. Tyree Scott founded the United Construction Workers of America and combined a campaign for racial and economic justice within the previously all-white building trades. Emphasis on community control and empowerment would continue to inform the next chapter of Seattle’s civil rights activism.

Copyright © 2008 Jessie Kindig

Sources:

Central Area Motivation Project website, history description, www.campseattle.org.

Congress of Racial Equality, Seattle Chapter, Records, 1961–1970, Suzzallo Library, University of Washington, Seattle, Manuscript 1563-001.

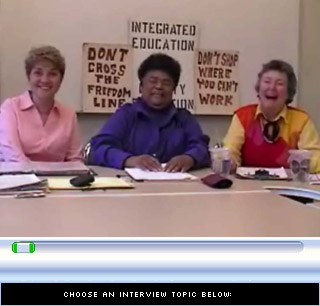

CORE oral history, Jean “Maid” Adams, Joan Singler, Bettylou Valentine, interview with Trevor Griffey and James Gregory, Seattle Civil Rights Project, CORE.htm.

Ivan King, interview with Trevor Griffey, Seattle Civil Rights Project, king.htm.

Quintard Taylor, Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era(Seattle: University of Washington, 1994).

Jeffrey G. Zane, America, Only Less So? Seattle’s Central Area, 1968–1996, Ph.D. dissertation (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame, 2001).