In 1964, the Seattle municipal elections helped establish a regrettable precedent for the treatment of the city’s African-American citizens. On the ballot was Proposition 1, the Open Housing Ordinance, which would have banned racial discrimination in real estate sales and rentals. The ballot measure was the culmination of years of struggle by civil rights organizations, political leaders, and individual citizens of all races. But the election ended in an overwhelming defeat. Seattle voters rejected the open housing measure by a margin of almost two to one. 55,448 voters supported the anti-discrimination law, while 115,627 said no. Four years would pass before City Council finally passed a law prohibiting discrimination in the sale and rental of housing.

Seattle’s mass media had an important and surprising impact on this election. This essay examines the newspaper articles, editorials, and paid advertisements in local newspapers, both the mainstream daily newspaper and several neighborhood and community weeklies.

What is surprising about this coverage is that at first glance it did not closely match the voter sentiments registered in the election results. Through much of the campaign open housing advocates seemed to be getting positive press coverage. Although coverage was not plentiful, newspapers did not openly take a stand against open housing legislation. In fact, the coverage seemed relatively good. If we judge voter sentiment on the basis of newspaper coverage, it might have appeared that Proposition 1 was going to pass, making the landslide defeat of the ordinance a surprise for its supporters. However, reading more closely, we see ambiguity and equivocation. And that ambiguity holds clues to why so many voters rejected open housing legislation.

Overall, it seemed that the common denominator among the newspapers was a reluctance to focus attention on the issue of open housing. Although most newspapers had articles that were relatively supportive of Proposition 1, they were not positive enough to sway people. Also, newspaper editors were not willing to take a stand either for or against the open housing legislation. It seems as though these editors were nervous or hesitant to touch upon the issue of open housing. This reluctance left Proposition 1 wide open for an aggressive attack that came in the form of anti-open housing paid advertisements.

Background

Before 1968 it was more or less legal to discriminate openly against Seattle’s minority population in housing. This included discrimination against prospective renters as well as homebuyers. One method, which was widely used to maintain this discrimination, was the enforcement of restrictive covenants. These covenants were written into the deeds of houses and legally forced the seller to discriminate against prospective homebuyers. Another method that was used was redlining, in which banks refused to loan money to African-Americans. These factors, coupled with generations of inequality, largely confined Seattle’s African-American community to the Central District neighborhood.1

Seattle’s open housing legislation was created in response to the open discrimination that was occurring in the city. Essentially, open housing legislation was a drive to make it illegal to discriminate against prospective homebuyers or renters based on race, religion, or gender. In order to determine whether open housing legislation was necessary, Mayor Gordon Clinton established the Mayor’s Advisory Committee on Open Housing in July 1962. Although the committee majority established that open housing legislation was necessary, the mayor and city council seemed to side with the minority report that disagreed with the majority’s decision. Many months passed without action for open housing legislation.

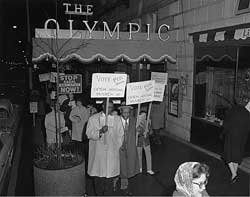

In July 1963 Reverend Samuel McKinney, an African-American civil rights leader, led a protest march designed to focus attention on the mayor and city council’s inaction on open housing policies. During the march, a small group of students broke off from the main protest and staged Seattle’s first sit-in. This sit-in took place in the mayor’s office and lasted for 24 hours. Eventually the students left without any arrests being made.

In response to this sit-in, subsequent protests, and the accusation that the mayor and city council were dragging their feet on the issue of open housing, Mayor Clinton created the Seattle Human Rights Commission. Within a year, this commission drafted the open housing ordinance. Written into the ordinance was an emergency clause that would allow passage of the ordinance immediately, avoiding a public vote.2 Although the commission highly recommended passage of the ordinance immediately and in its entirety, the city council declined to pass the ordinance as written. Pushed by councilman Dorm Braman, a city council member vocally opposed to open housing legislation, the city council removed the emergency clause and placed the ordinance on the ballot for March 10, 1964. The opposition to the ordinance included the Seattle Real Estate Board and the Seattle Apartment Operators Association. Supporters included the NAACP, the Human Rights Commission, and Mayor Gordon Clinton himself.

Seattle area newspapers played an important and surprising role in covering the March election. These papers include three dailies: the Seattle Times, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and the University of Washington’s campus newspaper, The Daily, plus several weeklies including The Facts, Ballard News Tribune, and the West Seattle Herald. Also examined are two monthly newspapers, the Washington State Labor News, and the Filipino Forum. The editorials, articles, and advertisements of these newspapers fall into two distinct categories, with some papers openly supporting and discussing open housing, and others either opposing or simply ignoring the referendum altogether.

The Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer

The Seattle Times was Seattle’s largest and most influential paper. Published by W.K. Blethen, the Times declined to take a clear editorial position on Proposition 1. This was unusual because Blethen would often make recommendations on the eve of major elections. For instance, just four days before the 1964 election, Blethen ran an editorial titled “Vote Against the Seattle Charter Amendment.”3 The Seattle Charter Amendment required Seattle’s transit system to increase electric trolley service in Seattle. As is made obvious by the title of the editorial, Blethen opposed the amendment and made his position brutally clear. However, when discussing open housing, Blethen did not take any clear position. This was an unusual approach for Blethen, because in another editorial (one of the few which even mentions open housing) he openly states that the open housing proposition was “of such import that it should draw every voter to his precinct polling place.”4 Regardless of the importance Blethen seemed to place on the issue, he refused to make a clear argument either for or against open housing. Blethen’s example illustrates a reluctance to openly editorialize on the subject of open housing legislation.

Readers would have seen numerous articles about the campaign in the weeks leading up to the election appearing in both the front page of the newspaper and in the local section. Without directly expressing opinions, most of this news coverage offered information that seemed to support the initiative.

One example of an article that provided support for the open housing campaign was titled “No Trouble Noted in Blacks’ move to White Neighborhood.” This article addressed and debunked many of the myths and negative stereotypes associated with residential desegregation. The article addressed the “top fears” of white homeowners concerning residential desegregation, namely decreased property value and the issue of “white flight.” The article cites the work of University of Washington associate professor of social work Lawrence K. Northwood, describing Northwood’s study of fifteen previously all-caucasian neighborhoods and how they changed after the introduction of an African-American family. As the article explained, 80% of the caucasian families did not experience a drop in property values. Of the remaining 20%, few could cite specific examples of proof of a value change. Furthermore, the study also found no cases of “white flight.” In the few cases where the most vocal objectors moved out of the neighborhood, other caucasians always bought their houses.5 This article was important because it demonstrated that white homeowners’ greatest fears about desegregation were factually baseless, and helped further the open housing campaign by alleviating commonly held misconceptions .

The Seattle Times also helped support the open housing campaign by publishing commentary by Alfred J. Westberg, an attorney, former state senator, and chairman of the Human Rights Commission. Westberg argued for the passage of Proposition 1 by claiming that freedom from racial discrimination was guaranteed by the federal and state constitutions. Westberg furthered his argument by stating, “no other group in American history had been so ‘kept down’ by discrimination and hampered in development than the Negro.”6 This article gave the citizens of Seattle a legal and ethical interpretation of open housing legislation. Westberg’s argument could easily have been influential in swaying some voters’ opinions of open housing.

Another Times article that supported the campaign was titled “Pacific Northwest Could Solve Race Problems, Say Experts.” The article reported the findings of Dr. Ernest Barth, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Washington. Barth claimed that the racial tension in Seattle had not yet become an insurmountable problem, but argued that Seattle must grasp its present opportunities to alleviate unrest, obviously referring to the open housing initiative. Included in the article is a brief excerpt from city councilman Wing Luke. Luke claimed that “the main weakness of the rights movement lay with the decent right thinking people who recognize the problems but do nothing about them.”7 In essence, Luke was attempting to mobilize people in support of the campaign for open housing. These two examples illustrate the kind of articles and arguments that helped promote the open housing campaign in the weeks before the election.

A fourth article supportive of Proposition 1 provided a detailed account of the opinion of West Seattle realtor, vocal supporter of open housing, and member of the Human Rights Commission Elliott Couden. Couden argued for the passage of open housing by emphasizing how the legislation would lead to the emancipation of non-white people, allowing them the same freedom to search for housing that caucasians have. He also argumed that fair housing legislation would free realtors from being forced to discriminate based on race for fear of reprisals from fellow white real estate agents.8 Couden’s insight as both a real estate agent and supporter of open housing created a bold line of defense in support of the legislation.

Although there were many articles that supported open housing, the Seattle Times also published articles by the legislation’s opposition. Located just to the right of Couden’s article was one by Donald C. Haas, president of the Apartment Operators Association. Haas argued that the serious economic losses apartment operators would face due to “white flight” outweighed the benefits of open housing. He went on to contend that open housing legislation as written failed to defend an apartment operator wrongly accused of discrimination by the would-be renter. Haas held that open housing legislation needed to consider defending homeowners from unfair charges of discrimination.9Although articles such as these opposed the open housing campaign, they were few and far between; the vast majority of articles published in the weeks leading up to the election were either outright or indirectly supportive of open housing legislation.

Another way the Seattle Times helped the open housing campaign was to run numerous articles listing the individuals and organizations that supported, or were urged to support, open housing. These organizations included Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish religious groups10 as well as the Junior Chamber of Commerce and the Teamsters Union of King County.11 Some of the individuals who were listed as endorsers included Mayor Gordon Clinton and Seattle city councilman Wing Luke. Articles such as these helped stir up support for open housing by showing the myriad of groups, institutions, and individuals that supported the open housing initiative.

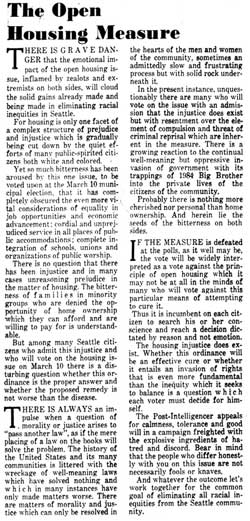

In respect to editorial content and the direct and indirect manner writers seemed to support the open housing campaign, the Times and the Seattle P-I were remarkably similar. The P-I was Seattle’s second largest newspaper, edited by Edward T. Stone, and the P-I habitually printed editorials before elections. Often, these editorials made the _P-I_editorial board’s position crystal clear: one month before the election for open housing was set to take place, Stone published multiple editorials pushing for the passage of a school levy.12 On the day the vote for the levy was set to take place, Stone printed a banner across the top of the front page reading “Vote Today—Don’t Forget the School Levy.”13 However, regarding the campaign for open housing, the _P-I_published only a single editorial. Furthermore, when compared to Stone’s earlier endorsements, this editorial took a rather indirect and muddled position toward open housing legislation. In the editorial, Stone’s official stance is that individual voters must make up their own minds on the subject of open housing. Stone agreed that housing injustice existed in Seattle, but claimed uncertainty as to whether Proposition 1 would act as a significant means of disabling discrimination or whether it would “create an invasion of rights that is even more fundamental than the inequality which it seeks to balance.”14 It seems that although the P-I addressed the issue of open housing and indicated that discrimination was occurring in Seattle, it chose to skirt the issue and was reluctant to take a clear stand on Proposition 1.

The fact that Stone directly mentioned the campaign for open housing in an editorial was one clear difference between the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and the Seattle Times. Another difference lies in the number of articles published by both these papers: although both papers subtly support open housing, the number of articles published in the P-I is far fewer than those in the Times. This is significant because the articles published by the Times covering the open housing campaign were not plentiful, indicating how little coverage the campaign was receiving. However supportive the publicity garnered by these major newspapers may have been, it remained true that the campaign for open housing was receiving very little exposure.

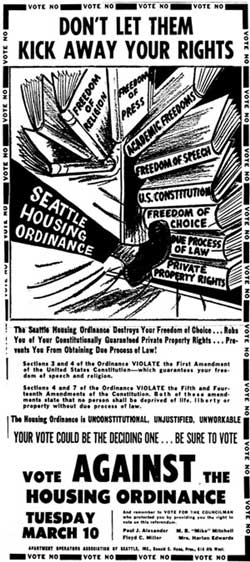

Despite the supportive, if infrequent, editorials and articles, both the Seattle Times and the Seattle P-I ran paid advertisements that brutally slandered the open housing campaign and helped defeat Proposition 1, allowing their papers to host an anti-open housing paid advertising campaign by Seattle’s real estate industry and the Seattle Renters Association. Opponents of the the Proposition waited until the final week preceding the March election before they hit Seattle voters with a blitzkrieg of advertisements designed to discredit the open housing ordinance.15 Many of these advertisements used the term “forced housing” rather than “open housing.” The ad campaign purposely overlooked the issue of housing discrimination, focusing instead on homeowner and property rights, trying to instill fear among homeowners and prospective owners. In one such advertisement published by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the concept of “forced housing” is emphasized: the advertisement is title, “On the Subject of Forced Housing.” The piece then asks the reader, “Are you willing?” Following this question is a list of twelve theoretical questions: for example, “1. Are you willing…to vote away your personal decisions as to whom you will sell, rent, or lease your home?” and “8. Are you willing…to empower the city to FORCE the choice of one individual over the right of another individual…maybe you?”16 Another example of an ad used in the forced housing campaign featured the words “INTEGRATION FIASCO” in bold lettering, in reference to open housing legislation.17 These types of paid advertisements were designed to instill confusion on the issue and frighten them into voting against open housing legislation.

Some of the most effective ads used cartoon images that relayed potent slogans. One published in both the _Seattle Post-Intelligencer_and the Seattle Times shows a leg marked “Seattle Housing Ordinance” kicking down a stack of books, titled “Freedom of Religion,” “Freedom of Press,” “Freedom of Choice,” “Private Property Rights,” and “Due Process of Law.” Above the comic it reads, “Don’t let them kick away your rights.”18 Another cartoon-based paid advertisement printed in both papers showed a man marked with the word “commission” standing upon the stomach of a defenseless man. In his hand, the “commission” man is holding a club marked “$500” which he swings above his head. Above the graphic image the advertisement reads, “Conciliation by Coercion…$500 fine (with a jail sentence if not paid).”19 This advertisement is clearly an attack on the Human Rights Commission that created the original draft of the open housing ordinance, highlighting the $500 fine and the possibility (however unlikely) of jail time for those disobeying the ordinance. Graphic images such as these were used to attack open housing supporters in the final week before the election, likely contributing to its downfall.

The Times and the Post-Intelligencer were the largest and most widely read papers in Seattle. Although their coverage of the open housing campaign and Proposition 1 was meager, it seems that the article coverage they did provide was indirectly supportive of the open housing campaign. Although neither editor took a direct stand either for or against open housing, the editor of the Post-Intelligencer did mention that Seattle had a housing problem and pushed individuals to decide the issue for themselves. The editors’ ambiguity, equivocation, and overall neglect of the open housing issue ceded ground to the hugely successful paid advertising campaign of the opposition, which helped crush the campaign for open housing, and insured failure of Proposition 1.

Washington State Labor News

Washington State Labor News was a monthly newspaper published by Clyde Dunn and edited by Stan Craft. As the official voice of the AFL-CIO of King County, Washington State Labor News reported on issues that affected unions and working-class individuals. Because the paper predominantly emphasized local politics, it was highly unusual that the open housing ordinance was mentioned in its pages only rarely.

The paper’s neglect of the issue was made clear in a list of political endorsements found on the front page of the paper one month before the election was about to take place. The list was made to resemble a voting pamphlet, with certain boxes already checked off, indicating who and what the King County Labor Council Board endorsed and wanted its supporters to vote for. The pamphlet contained mayoral candidate John Cherberg, four city council members, a candidate for corporate council, and a “yes” vote for the school levy. Surprisingly, the only issue that the pamphlet seems to leave off is open housing.20 In fact, open housing was not mentioned at all by this newspaper in the weeks and months leading up to the March 1964 election.

Although the campaign for open housing legislation was an issue that at the very least warranted mentioning for most of Seattle’s newspapers, it seems to have completely bypassed the Washington State Labor News. The controversy behind Proposition 1 seems to have made the editor of this paper too nervous to take a solid editorial position, or even mention it.

The Filipino Forum

The Filipino Forum was a monthly publication edited by Victorio Acosta Velasco. The Filipino Forum took a rather ethnocentric stance regarding many local issues at this time, and dealt primarily with issues pertaining to Seattle’s Filipino community, with topics ranging from fashion and local beauty queens to political events in the Philippines. Although the Filipino Forum did discuss politics, it did so only in the context of events directly relating to the Filipino community. One editorial, titled “The Way It Looks to Me” by William H. Jordan (a guest editor), focused on getting the Filipino vote organized. The final emphasis of the article stressed, “If you believe in democracy then keep informed. Go to your party meetings, give a dollar to your party and then vote!”21 This was one of the only articles in the months leading up to the election that emphasized any kind of involvement in Seattle-area politics. Because the paper took such a narrow view, its official stance on open housing remains a mystery. Whether the paper stood for or against open housing is unknown, it seems that the Filipino Forum simply stayed out of this political battle all together. It was no different in the weeks before the election. Although other area newspapers, even the ones that ignored Proposition 1, were editorializing and publishing articles discussing local elections and the mayoral race, the Filipino Forum failed to take an editorial stance on any issues relating to the election, except for a few paid advertisements for the Cherberg campaign.22

The Facts

The fledgling African-American run newspaper The Facts was the only Seattle-area newspaper that strongly supported open housing legislation. Edited by Fitzgerald Beaver, and based out of the predominantly African-American neighborhood of the Central District,The Facts focused on news that related to African-Americans living in Seattle and throughout the United States. The Facts was specifically dedicated to furthering the civil rights campaign and building strong black communities. This paper’s editorials and letters to the editor are extremely significant because the Central Area was on the front line of this campaign: many of the paper’s articles and editorials provide insight into the civil rights and housing struggles taking place within the neighborhood at this time.

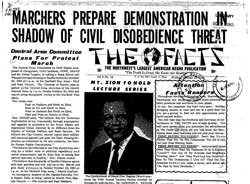

In a front-page article entitled “Central Area Committee Plans for Protest March,” The Facts made its position on the open housing campaign clear. Calling for civilian involvement, this article provides the reader with dates, times, and travel routes through the city that protest marchers would take in a demonstration of support for open housing legislation. The language used in the article also reflects the newspaper’s support for open housing: quoting Reverend Adams, a well-known Seattle civic leader, the article argues that the Central District’s African-American population was being exploited economically. Adams compared the prejudice of Seattle’s real estate board and apartment owners’ interests to the bigotry of Alabama Governor George Wallace and Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, and went on to attack Seattle’s mayor and city officials by claiming that “officials of our city should stop serving as a buffer zone of political expediency and moral compromise and do their duty in seeing that justice operates in Seattle.”23 The Facts is the only Seattle-area newspaper that used such straightforward language in regards to the issue, made more forceful by printing their articles on the front page of the paper. This illustrates a strong desire to increase public support for open housing legislation.

The Facts was also used as a forum to organize African-American voters and increase black voter turnout and participation in Seattle politics. To this end, the paper emphasized organizations like the Voter Action Committee, the NAACP, the Urban League, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the League of Women Voters and their Votes-wagon. As an editorial explained, the League of Women Voters’ Votes-wagon increased the number of African-American voters by creating a mobile force of volunteers to register potential voters in the Central District. 24 A later article praises the work done by these organizations and declares that they have registered some 1,200 voters, a number previously unprecedented before a city election. The article describes the increased voter turnout as a very real sign of the growing electoral strength of Seattle’s Central District.25

The Facts also hoped to inspire people to vote through its editorials. One such piece, written by Fitzgerald Beaver, argued for an increase in African-American voter turnout, reading “At no time in the history of Seattle has your vote meant as much as it does now. As a neighbor and friend, I beg of you to go to the polls and vote…If citizens in the Central Area would stop sitting on their _____ and get out and vote, then we could elect to the City Council responsible people.”26 Not only does this passage exemplify the types of editorials written to influence citizens to vote, but it also conveys a sense of political community throughout the Central District. In the editorial, Beaver gives the sense that he is discussing local issues with his neighbors and trying to convince them to do their civic duty.

The sense of local political community on the pages of the paper was largely due to the fact that its editor, Fitzgerald Beaver, lived and worked in the Central District, as did most of the paper’s staff. This close proximity to the battlegrounds of the open housing campaign provided Beaver with firsthand knowledge of the Central District, the issues of open housing, and a personal investment in the outcome of the election. Openly proud of his neighborhood, Beaver defended the Central District in an editorial in response to his associates’ questioning of his continued residence in the Central District, rather than more affluent neighborhoods like Mercer Island. Beaver responded by arguing that any neighborhood is what you make of it and that African-Americans in the Central Area needed to get involved in community organizations that could work toward building a better community. “Let’s all pull with others who are trying to make the Central Area (District) a better place to live, then we can never see or hear that Seattle has a ghetto.”27 Beaver’s comments indicate that he was trying to rally the people living in the Central Area to improve their lives and place within society, and also makes evident that the paper—run by African-Americans and with close ties to the Central District—would be directly affected by the outcome of the open housing vote.

_The Facts_’ attempts to increase African-American voter turnout in the Central District was not only designed to increase African-American involvement in local government but was also in response to a campaign within the African-American community to boycott the open housing referendum. The issue of open housing legislation and the drive to boycott this vote divided Seattle’s African-American community. As one letter to the editor reads, “It is also our contention that the rights of individuals…should not be determined by the majority via the ballot…we urge all citizens to register to vote, vote for the candidate of their choice, and to boycott the Fair Housing Referendum.”28 There were many African-Americans in the Central District who felt that it was absurd that basic human rights, such as open housing, should be put up for a vote. Out of frustration, these individuals responded by calling for a boycott of Proposition 1. This letter serves not only to help us understand one possible reason for the overwhelming defeat of open housing during the election but provides us with some idea of how divided Seattle’s African-American community was over Proposition 1.

The Facts also ran letters to the editor from white Seattleites’ attempts to integrate their communities without the use (or need) of legislation. As indicated in an open letter written by a Mrs. D.L. Shoenfeld, there were white citizens who were for integration and proactively striving for racial equality in housing. “We would regard any new neighbors equally, with a little plus on the side of justice for the deprived.”29 To be sure, The Facts is the only paper in Seattle that printed letters of invitation such as this. This passage shows that not all of white Seattle was against the concept of open housing, and that The Facts was open to showing this part of white Seattle.

The Ballard News Tribune

Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood also had a local newspaper, the Ballard News Tribune, which was a conservative, bi-monthly publication. Its focus was on local politics that related to the predominantly white enclave of Ballard and occasionally the greater Seattle area. Designed to support and build a strong community in Ballard, the _News Tribune_often editorialized their support for specific political issues, city officials, and campaigns.

Although the newspaper was abuzz with political commentary in the weeks before the March 10 election, the editor made no mention of open housing, yet did publish his opinion on a proposed transit bill in the same election, arguing that it would be a backwards step designed to restore an obsolete trolley system.30 In another editorial, the News Tribune openly endorsed the campaigns of J. Dorm Braman for mayor and city council incumbents Paul Alexander and M.B. “Mike” Mitchell. All of these candidates were running conservative campaigns that openly opposed open housing legislation. In fact, what is missing from both of these editorials (and indeed all editorials throughout this paper) is any mention of the open housing campaign at all. It would appear that the Ballard News Tribune attempted to oppose open housing legislation, not openly, but by supporting the campaigns of open housing’s political opponents.

To prove this further, the Ballard News Tribune published an article on unconstitutionality roughly one month before the vote for open housing took place. The article was designed to enlighten readers on laws that are deemed unconstitutional and provided them with the necessary congressional steps that could be followed in opposition to laws that attacked the constitutional rights of individuals.31 The emphasis on individual rights, and the argument for the constitutional rights of homeowners to sell to whomever they choose, coincides with the real estate boards’ “forced housing” terminology. The _Ballard News Tribune_’s article on unconstitutionality reflects this supposed concern among white homeowners. It should be noted, however, that there is no mention of the “forced housing” campaign throughout the article on unconstitutionality.32

West Seattle Herald

The West Seattle Herald was another neighborhood paper, a weekly publication edited by Stan Craft based in the neighborhood of West Seattle. Although this newspaper did not have a long history of liberalism, it endorsed mayoral candidate John Cherberg, who was a supporter of open housing legislation. The paper also made efforts to discuss and publish information regarding the open housing campaign while other Seattle-area papers did not, which made it unusual among Seattle’s print media.

At times, the West Seattle Herald printed editorials and articles that seemed to offer support for the open housing campaign. For instance, one article illustrated West Seattle’s involvement in the campaign for open housing. The article described how West Seattle voted to give full support to the citywide open housing demonstrations, and provided readers with the time and place to meet if they wished to participate in the pro-open housing demonstration.

The West Seattle Herald also published discussions of the campaign, creating a forum for lively debates. One such discussion began at the West Seattle Commercial Club, where Mayor Gordon Clinton spoke on behalf of the open housing ordinance. In his speech, Clinton expressed his desire to make housing available in Seattle on a financial, not a racial basis, arguing that open housing legislation would make this possible. Clinton also argued for the importance of the emergency clause that would have immediately enacted the legislation without a public vote, arguing that it would provide Seattle with a trial period to more fully understand open housing legislation before voting on it. In opposition to Mayor Clinton was Orville Robertson of the Seattle Real Estate Board. Robertson spoke out against the open housing ordinance, maintaining that the law “represents governmental control.” Robertson also argued that Seattle was moving “peacefully and quietly towards integration,” but that this ordinance would destroy this progress. Robertson ended his speech by asking, “If this experiment is forced on us and it fails, how do you restore your rights once they have been taken from you?”33 This article illustrates that the West Seattle Herald was willing to publish both sides of the issues concerning open housing.

Another discussion began with an article introducing the Seattle Voting Rights Committee (SVRC). Based in West Seattle, the SVRC objected to the passage of the open housing ordinance with an emergency clause, which would have bypassed the March 10 election. The SVRC argued that “The right to freely hold and dispose of private property is a basic human right,” and held that open housing legislation was unconstitutional on the grounds that it attacked these basic human rights. SVRC ended their argument by proclaiming that “it is neither logical nor just to pass this law without first submitting it to the vote of the people.“34 In response to this article, the _West Seattle Herald_published a letter from an allied group of ministers who supported fair housing in West Seattle. In their letter, these ministers argued against the SVRC’s interpretation of the open housing legislation; while they agreed with SVRC’s defense of human rights, they contended that the right to freely hold and dispose of private property did not give the seller the right to “hurt or humiliate other human beings.” The ministers further clarified their case by stating that the ordinance did not take away sellers’ rights to “exercise judgment and discretion in the sale or rental of property” but only kept them from discriminating on the basis of race. These ministers ended their response by urging readers to become “thoroughly familiar” with the open housing ordinance.35 The fact that the West Seattle Herald was willing to publish the points and counterpoints surrounding the debate for open housing indicates a willingness that many other Seattle-area newspapers did not demonstrate.

The West Seattle Herald also printed many letters to the editor that offered support for open housing. One letter written by Alfred J. Westberg, chairman of the Seattle Human Rights Commission, openly supported the ordinance. Westberg’s objectives were to educate the readers of the West Seattle Herald on the true objectives of the ordinance and attempt to garner community support for the emergency clause. The clause, Westberg argued, would give Seattle’s citizens several months of experience with open housing legislation, “showing them that the law is reasonable and fairly administered,” and arguing that justice delayed is justice denied, claiming that there is no excuse for further delays on passage of Proposition 1.36 Letters such as this were not found in most other Seattle-area newspapers at this time, adding to the _West Seattle Herald_’s unique approach to issues of open housing.

Although the West Seattle Herald was unusual in that it printed articles and letters discussing open housing where others did not, and at times it seemed to take a balanced view of open housing, the paper itself remained divided on this issue. Stan Craft, the editor, seemed to support the issue of open housing. In his editorials entitled, “Better Left Unsaid…” Craft’s generally supportive attitude toward open housing emerges. In one instance, Craft compared the seemingly contradictory position of Seattle’s clergy toward emergency clauses as they relate to the open housing ordinance and the city’s recently defeated gambling laws. The editorial pointed out that Seattle’s clergy, who want a trial period for open housing, were adamantly opposed to a trial period for the gambling law. Craft’s argument provides insight into his personal views on open housing. For instance, Craft agreed with Seattle’s clergy on the importance of passing open housing legislation with an emergency clause so that the city may try the ordinance out before they vote on it. Craft’s emphasis of a trial period indicates that he supported the basic principles of open housing and believed that, if given the opportunity to try it out, Seattle’s white community would be more inclined to accept it.37

Although Craft seemed to support open housing legislation, there were other members of the paper’s staff who stood against the issue. In one editorial, Craft comments that he plans to vote for the ordinance, but indicates that other people he knows will vote against it. As divided as this paper was, Craft’s stance shows that the West Seattle Herald was progressive enough to openly debate the issues of open housing within articles and editorials. The West Seattle Herald was unique among Seattle’s newspapers because rather than neglecting or only directly or indirectly voicing support for open housing, the _Herald_allowed open debates about the measure to appear in its pages.

The Daily

The University of Washington’s newspaper, The Daily, was a student-run newspaper edited by Ruth Pumphrey. This newspaper reported on Seattle-area politics and issues of relevance to students. _The Daily_’s articles were generally supportive of open housing; however, like other mainstream dailies such as the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, these articles were few and far between. However, The Daily was different from these larger dailies in that the editorial section did not avoid the issue of open housing. Overall, The Daily approached the issue of open housing in a fair manner, often referencing and discussing the issue, albeit on a fairly small scale. In this respect, _The Daily_’s approach to open housing seems strikingly similar to the approach taken by larger dailies in the Seattle area.

_The Daily_’s editorials differed from the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in that it did editorialize on the open housing campaign. One interesting editorial addressed an aspect of the campaign for open housing that had not been mentioned previously by any media outlets. Pumphrey’s editorial addressed the “widespread” belief that Proposition 1 had no chance of passing and the notion that “everyone feels so sure it will lose and the number feeling this way is overwhelming.” The editorial goes on to give credit to those who are promoting the ordinance, arguing that the energy that these proponents of open housing displayed was honorable, even if they secretly believe that the proposition will not pass. The editorial ends with a description of the ordinance as “so weakly worded, it will neither infringe on the rights of property owners nor protect Negroes from discrimination. It is only a token and Seattle doesn’t even think it can swallow that.”38 This editorial was one of the few suggesting that supporters knew the open housing campaign was in trouble, yet it also indicates that the issues behind the ordinance are relevant and that the supporters of the ordinance are doing good work. This demonstrates that The Daily was free to editorialize about the issue of open housing and that there was a certain level of support for Seattle’s African-American community that was lacking in most of Seattle’s larger newspapers.

One place where the debate for open housing did play out was in newspaper’s letters to the editor section. So heavy was the flow of letters discussing open housing that the editor published these letters under headlines such as: “Letters: Readers Have Lots To Say On…You Guessed It,” and, “Letters: More on Open Housing.”39 These titles indicate that The Daily was receiving large amounts of letters every day from students eager to discuss open housing. This illustrates a level of interest and a profound desire to discuss the subject of open housing that was not found—or encouraged—in many other Seattle-area newspapers.

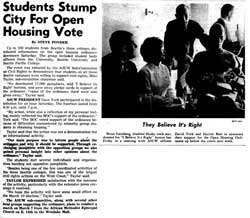

The Daily was similar to other Seattle-area dailies in that the articles it published were subtly supportive of the campaign for open housing. One way that _The Daily_’s articles subtly supported Proposition 1 was by providing students with information regarding events that supported the open housing campaign. For instance, one article, titled “Students Stump City for Open Housing Vote,” focused on students, one of them the student body president, from three Seattle-area universities who took an active role in support of open housing by distributing informational pamphlets. The article ends with a call for a march in support of open housing, including dates and meeting times. Articles such as these influenced students by illustrating how their peers were getting involved. They also acted as a catalyst for the open housing campaign by providing students with information on how to get involved.

Although The Daily did provide its readers with a level of information regarding Proposition 1 that they would not find anywhere else, it published relatively little about the campaign. In this way, _The Daily_was similar to larger daily newspapers such as the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. However, The Daily was a rare newspaper because it did not avoid the issue of open housing in the way that most other Seattle-area newspapers did, publishing letters to the editor discussing open housing and editorializing on the campaign.

Conclusion

The Seattle-area newspapers’ coverage of the open housing campaign varied to a huge degree. There were some newspapers that clearly supported and believed in Proposition 1, yet the majority of Seattle-area newspapers seemed reluctant to endorse, or even report on, the open housing campaign. Surprisingly, this included other Seattle-area ethnic newspapers such as the Filipino Forum. This overall reluctance to openly address the issues surrounding Proposition 1 set up the ordinance for a crushing defeat in the March elections by a margin of two to one. Seattle-area newspapers’ lack of content concerning Proposition 1, and the editors’ skirting of the issue of open housing was instrumental in this defeat. Despite a Seattle Times editorial published shortly after the campaign which emphasized the need for renewed efforts to decrease racial segregation,40 it was not until 1968 that Seattle’s African-American community was finally allowed a degree of legal protection against open racial discrimination in the housing market.

Copyright © 2008 Trevor Goodloe

HSTAA 498 Fall 2007

1 Housing Segregation and Open Housing Segregation. Anne Frantilla, Seattle Municipal Archives Online. July 2, 2008. http://clerk.ci.seattle.wa.us/~public/doclibrary/OHousing/narrative.shtml

2 Frantilla, Seattle Municipal Archives Online. July 2, 2008. http://clerk.ci.seattle.wa.us/~public/doclibrary/OHousing/narrative.shtml

3 The Seattle Times, March 6, 1964, p. 8.

4 The Seattle Times, March 8, 1964, p. 8.

5 “No Trouble Noted in Blacks’ Move to White Neighborhood,” The Seattle Times, October 20, 1963, p. 24.

6 “Attorney Envisages Chance for Racial Harmony in Ruling,” The Seattle Times, October 20, 1963, p.24.

7 “Pacific Northwest Could Solve Race Problems Say Experts,” The Seattle Times, March 8, 1964, p. 9.

8 “Realtor, Member of Rights Group, Backs Open-Housing Plan,” The Seattle Times, October 20, 1963, p. 23.

9 “Head of Apartment Operators, Opposes Open-Housing Law,” The Seattle Times, October 20, 1963, p. 23.

10 “City’s Clergy Strongly Support Open-Housing,” The Seattle Times, March 8, 1964, p. 50.

11 “Teamsters Tell Stand on Candidates,” The Seattle Times, February 27, 1964, p. 6.

12 “Vote!” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 5, 1964, p.12; “Vote For Levy,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 10, 1964, p. 14.

13 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 11, 1964, p. 1.

14 “The Open Housing Measure,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 28, 1964, p. 38.

15 “Housing Debate to Grow Warmer This Week,” The Seattle Times, March 1, 1964, p. 14.

16 “Are You Willing?” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 2, 1964, p. 9.

17 “Integration Fiasco,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 8, 1964, p. 21 and 70.

18 “Don’t Let Them Kick Away Your Rights,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 9, 1964; “Don’t Let Them Kick Away Your Rights,” The Seattle Times, March 8, 1964, p. 50.

19 “Conciliation By Coercion,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 7, 1964, p. 18; “Conciliation by Coercion,” The Seattle Times, March 6, 1964, p. 24.

20 “King County Labor Council Endorsements,” Washington State Labor News, February 1964, p. 1.

21 “The Way It Looks to Me,” The Filipino Forum, September 6, 1963, p. 4.

22 “Vote Cherberg,” Filipino Forum, March 2, 1964.

23 “Central Area Committee Plans for Protest March,” The Facts, October 18, 1963, p. 1.

24 “Vast Turnout for Voter Registration In Central Area,” The Facts, January 15, 1964.

25 Editorial, The Facts, December 5, 1963.

26 “From the Publisher’s Pen,” The Facts, March 5–11, 1964, p. 2.

27 Editorial, The Facts, February 13–19, 1964, p. 2.

28 Letter to the editor, The Facts, February 13, 1964, p. 2.

29 Open letter, The Facts, November 21, 1963, p. 2.

30 The Ballard News Tribune, March 4, 1964, p. 1.

31 “Unconstitutionality,” The Ballard News Tribune,. February 19, 1964, p. 4.

32 The Ballard News Tribune, February 19, 1964, p. 4.

33 “Speakers Take Opposite Views Before Local Club,” West Seattle Herald, October 10, 1963, p. 1 and 13.

34 “Local Group Fights Open Housing Law,” West Seattle Herald, October 3, 1963, p. 1.

35 “Letters to the Editor,” West Seattle Herald, October 10, 1963, p. 2.

36 “Letters to the Editor,” West Seattle Herald, September 6, 1963, p. 2.

37 “Better Left Unsaid,” West Seattle Herald, September 26, 1963, p. 2.

38 “They Can Win,” The Daily, March 6, 1964, p. 2.

39 “Readers Have Lots To Say On…You Guessed It,” The Daily, March 5, 1964, p. 3; “More on Open Housing,” The Daily, March 4, 1964, p. 3.

40 “Aftermath of the Election,” The Seattle Times, March 12, 1964, p. 8.