What do we want? Integration. When do we want it? Now! This familiar chant from the civil rights movement reflected the desires of Seattle parents of school age children in 1966. That year, for two days, K-12 students poured out of Seattle ’s public schools and attended “freedom schools” to protest racial segregation in the Seattleschool system. Excitement was in the air as the students learned about African America history that was not taught in the public school system. All organizers and participants were striving for an end to segregation, and for two days, the students attended integrated schools, and used an innovative kind of direct action to turn their schoolwork into activism for social change. This essay tells the story of that boycott—from its origins to its effect on Seattle’s students and politicians.

IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

The problem of segregation in Seattle was very easy to identify, as it was across the entire country. But the solution was very complex. De facto segregation—in which public spaces were supposedly integrated but housing and employment discrimination still confined African Americans to certain poor neighborhoods—was the problem in the north. This kind of segregation—different from the explicit prohibitions in the South— proved difficult for supposedly liberal Seattleites to acknowledge or take action to remedy. When interviewed by the Seattle Times, one black Seattle resident commented that, “The biggest fault most Negroes find with the Seattle white-power structure is that it doesn’t seem to recognize the problem even exists.”1

In Seattle , as in other major cities, blacks were concentrated in one area. The Central District—also called the Central Area—was home to a majority of blacks and thus resulted in many schools being mainly black. According to Seattle ’s major civil rights groups, this concentration had a negative impact on the quality of African Americans’ public education.

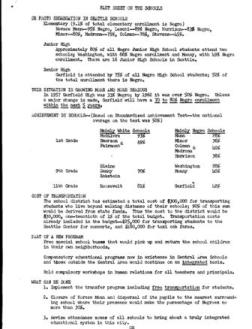

In a flyer put out by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), and the Central Area Civil Rights Committee (CACRC), they state that Seattle had thirteen predominately “black” schools and over 100 “white” schools. In the Seattle schools, blacks accounted for 9.1 percent of total enrollment. However, the black students were heavily concentrated in a small number of schools. In elementary schools, black students made up 95 percent of Horace Mann; 89 percent of Leschi; 83 percent of Harrison ; 80 percent of TT Minor; 79 percent of Madrona; 76 percent of Colman, and 45 percent of Stevens. About 80 percent of all black students attended two junior high schools, which made Washington 66 percent black and Meany 49 percent. Garfield High School was home to 75 percent of all black high school students, who made up 52 percent of the entire school’s student body…2

Segregated schooling was part of a much larger cycle of segregation, and it perpetuated segregation in employment, housing, and every day of these students’ daily lives. These schools had less funding, less parent involvement, less experienced teachers, lower test scores, and lower graduation rates.

But African American parents were not passive. They fought both to improve the quality of their schools while challenging the system that concentrated African Americans disproportionately in a few under-funded schools. The problem they had was getting residents and officials in the city of Seattle to take their concerns seriously.

UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPTS AT DESEGREGATING THE SEATTLE PUBLIC SCHOOLS

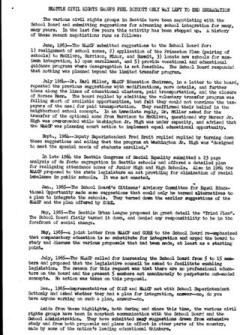

Throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, various civil rights groups in Seattle unsuccessfully tried to persuade a predominately white school board to address the issues of desegregation of the Seattle Public Schools. The school district’s representatives argued that the neighborhood school was the best, and that all children should be able to live near and walk to their school.

Dr. Ronald J. Rousseve, Associate Professor of Education at Seattle University , explained why he and much of the civil rights movement disagreed with the school board’s response. For him, the “neighborhood school concept” served an unacceptable status quo. The de facto segregated schools were perpetuated through residential stratification and adherence to the neighborhood school concept. He argued that “Stereotypes, racial epithets, unconscious prejudices, and both subtle and overt discrimination are still so pervasive in our society (and this includes the Pacific Northwest), that children from different social backgrounds cannot possibly learn to relate to one another as individuals if they are kept separated most of their childhood years.”.3

Civil rights groups in Seattle tried for years to open up the Seattle school system. They were in constant communication with the School Board; the NAACP submitted suggestions and letters; CORE submitted a 23 page analysis of school segregation which included a plan to eliminate it.4 And in May, 1965, the Urban League submitted a different plan-the Triad Plan— which came to dominate early school desegregation battles.

The Triad Plan would have desegregated all tiers of the school system by matching white schools with those that were predominately black. 5 The elementary schools would be divided into two year institutions and the city would be divided intozones. The students from neighborhoods that fell within the paired zones would go to one school for grades 1-2, another for grades 3-4, and yet another for grades 5-6. Each one of these schools would be located in a different area, which would provide multiethnic education for all students.6 The basic philosophy was “the need to provide every child, especially the disadvantaged child, with an enriched, expanded community with which to identify.”7 There were many who supported this proposal as a solution to the problem of segregation, but those supporters did not include the school board.

PLANNING FOR THE BOYCOTT

Cold response to the Triad Plan, along with years of fruitless negotiations, began to convince Seattle’s civil rights leaders that more dramatic actions were necessary to push the Seattle School Board to take action to remedy the effects of de facto segregation in Seattle’s schools.

One observer summarized the School Board’s stand in 1965 by commenting that “compensatory education would be offered in the Central Area, that the voluntary transfer program would be maintained, and that the schools weren’t all that bad anyway—that everyone had equal access to education.”8 But this did not satisfy Seattle ’s civil rights leaders. Rev. John Adams of First AME Church remarked that “I consider the whole compensatory education program a deception and a fraud. The very name defeats its purpose. It says to the Negro children that they have learned less than they should. They accept it, believe it, and do as little as possible.”9 An article in Seattle CORE’s newsletter, The Corelator, added that “compensatory education is like rain on sand. It leaves a mark for a while, but soon disappears.10

As early as 1965, the president of the Seattle NAACP, E. June Smith, warned that “if the Seattle School Board does not devise a long-range school integration program and begin implementing it next fall, we will have to dramatize our concern.”11 She went on to state that the action would be direct and might include a boycott, sit-in, or other methods of direct action. She concluded that the voluntary transfer program was only a minor concession and had not been successful in any other city that it had been tried out.

The President of the School Board, Phillip B. Swain, responded to Smith by saying that “the only person ultimately hurt [by a boycott] is the child himself, who is deprived of educational experience.”12 He claimed that school board policy stated explicitly that “it has a responsibility to promote racial understanding within the broad application to promote racial understanding within its broad obligation to provide high-quality education programs for all pupils.”13He also noted that “forced racial segregation was contrary to the basic principles of our society; that equal educational opportunity must be provided for all children with special programs to assure that cultural deficiencies are overcome”; that each child “must be accepted and treated by every member of the school staff without prejudice or bias.”14

In early February of 1966, the rest of Seattle ’s civil rights leaders came to a similar conclusion as Smith. Walter Hundley, chair of CORE and member of the CACRC, got together some fellow CACRC members; John H. Adams, Minister of First A.M.E church, Edwin Pratt, Executive Director of the Seattle Urban League and Charles V. Johnson from the NAACP for lunch to lay out the need for action in the schools from his CORE perspective and suggested that a boycott was necessary. Hundley recalled:

I told them, you know the schools…the CORE committee wasn’t able to get anywhere with the School District —there were just a lot of games being played. I said, “We’ve got to do something…we’ve really got to move this thing—and its got to be dramatic.” And I suggested that we have a school boycott, but that we must do it in the most responsible manner possible… it’s going to be a lot of work for everybody. The organizational logistical kind of thing would…be tremendous—but I think we could pull it off.” And we kicked it around—and Adams said, “You’re right! Right on!” And then the others fell in line.15

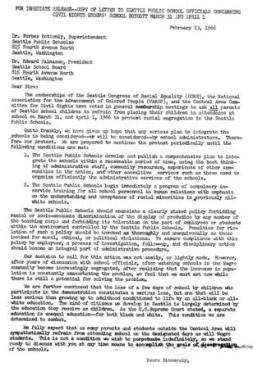

On February 23, 1966, the NAACP, CORE, and CACRC, released their letter to the superintendent to the press which spelled out their intention to launch a boycott of the Seattle public schools. They requested that all parents in Seattle keep their children out of school for two days. They had given up hope that any serious plan to integrate the schools would be considered. This was why they felt so driven to protest and vowed to continue their protest until the Seattle Public Schools met two conditions:

- Develop and publish a comprehensive plan to integrate the schools within a reasonable period of time…

- Begin immediately a program of compulsory in-service training for all school personnel in human relations with an emphasis on the understanding and acceptance of racial minorities in previously all-white schools.16

This decision to boycott was not made on a whim; there had been years of fruitless discussion with school officials.

Their goal was not to protest indefinitely, and they were “ready to discuss…at any time means to accomplish the goals of desegregation of the schools.”17 John Cornethan, Chairman of CORE, said that “This boycott is not necessary; it is the last thing we want to do…But the school board has not been at all receptive to our suggestions.”18 He thought the boycott should never have had to happen, but nothing else was working. Rabbi Levine said, “This is the real reason for the threatened boycott. It is not to intimidate the school authorities and force them to action. It is rather an act of desperation on the part of the civil rights leaders to shock the community into an awareness of the problem and acceptance of our responsibilities.”19E. June Smith of the NAACP said she thought the boycott would be called off if there was something done, but a plan would need to be spelled out. A promise that something would be done would be unacceptable, and would be willing to meet with official at any time but never heard from them.

The Superintendent thought the boycott was unnecessary since they already knew about the situation. He thought it would have little or no effect on the plans to end segregation and that “there are certainly more constructive ways for these people to accomplish their ends,…[the boycott] would have no adverse effect on any desegregation plans…[nor] affect the board’s desire and ability to move ahead…[but] the board will not and cannot operate under pressure.’”20

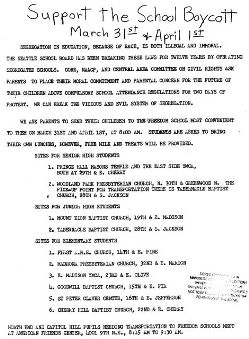

The boycott was publicized through city-wide and leafleting, but the biggest planning problem was what to do with the children who were participating in the boycott. The organizers didn’t want to take students out of school entirely and saw the need for some type of substitute program which would stress the importance of school during the two days of protest. This concern led to the formation of a “freedom school” planning committee within the general leadership group.

The term “freedom school” was first used during Freedom Summer in 1964, during which CORE established 30 freedom schools throughout Mississippi to dramatize the racial inequalities in the state’s educational system. These schools were staffed by white college students who tried to overcome poor funding and outdated textbooks by teaching them black history and leadership skills.21

On March 6, Rev. John Adams announced the Seattle freedom school plans to the public. There would be a committee of educators arranging for a staff to teach the students participating in the boycott black history, life and culture. He reassured that the boycott was not “meant to be a holiday; it would be an educational experience as well as a protest of the…failure to end racial segregation in the schools here.”22 And he stressed that a “substantial number of white people…[would join the] protest and participate in operating the freedom schools.”23

The eight freedom schools were to be staffed by 100 teachers with two principals at each site. The sites for elementary schools were planned for First A.M.E. Church , Madrona Presbyterian Church, East Madison YMCA, Goodwill Baptist Church , St. Peter Claver Center, and Cherry Hill Baptist Church . The junior high centers were planned for Mt. Zion Baptist Church , and Tabernacle Baptist Church , while the senior high school sites consisted of Prince Hall Masonic Temple , East Side YMCA, and Woodland Park Presbyterian Church.24 Volunteers served as doctors on call, resource people and general assistants. The schools’ main focus was black history and civil rights. One of the principle planners, Nancy Norton, said they wanted to use “’good solid material that all children can do well together,” and their aim was “’to promote a good integrated experience for the children who came to the schools.’”25 There was much speculation about how many students would participate in the freedom schools and boycott. John Adams was sure that the freedom schools could handle as many as 5,000 students, while others felt that 500-700 in attendance would be a success.

SUPPORT AND OPPOSITION FOR THE BOYCOTT

The decision by parents, churches and organizations to either support or oppose the boycott was often complex. The boycott highlighted tensions within the community: some were neutral, some were vehemently opposed, and some were all for it. And much of the debate was centered on whether a boycott was legal, and what kind of citizenship students would learn through freedom schools.

Many organizations issued their full support for the boycott and freedom schools. The New Conference of Women’s Auxiliaries of the International Longshoremen’s Union endorsed it as well as the Seattle Local 200 American Federation of Teachers. Local AFT president Jim Sullivan said, “We think it is unfortunate to have to us such things as boycotts, but historically the Negro has not achieved any breakthrough without some form of direct action.” The Madrona PTA would not state whether or not they would support the boycott. Churches provided a major source of both support and opposition. Father John Lynch was very involved in CORE planning movements which was an early indicator of Catholic support for the boycott. The executive board of the Catholic Interracial Council issued a statement in March which supported the boycott.26 The Archbishop of Seattle, the Most Reverend Thomas A. Connolly, was also a firm backer of the protest. Unitarians for Social Justice also passed a resolution supporting the boycott. The Reverend Peter Raible, minister of the UniversityUnitarian Church , supported the boycott and was scheduled to be involved in the freedom schools.

The Presbytery of Seattle supported the freedom schools but did not endorse the boycott. The Seattle Association of Evangelicals opposed the boycott as an illegal action. They felt that the students were the ones who would suffer and the end result was not justified by the means. Rev. Dr. Robert B. Munger of University Presbyterian Church argued that “dramatic steps” must be taken to awaken the community to growing segregation, but he disagreed that “the ends justified the means.”27 One clergyman stated, “I support the cause wholeheartedly, but not the method.”28

The local mainstream newspapers did not endorse the upcoming boycott. The P-I labeled it as a “crisis of conscience.” The Seattle Times called the boycott “ill-advised” and said the schools’ “primary function is education, not social reform.” It added that “no major public agency in the state has shown more concern about racial problems than the Seattle Public Schools.” The Times worried that the boycott would teach children to defy public authority. It supported the school board in “refusing to be stampeded into making concessions”, and hoped “that the boycott will find mighty few participants.”

ACLU attorney Michael Rosen countered such arguments by saying that it was the school board, and not protesting students, who were violating the law. Since the Supreme Court ruled segregation illegal, and the schools in Seattle are overwhelmingly segregated, he reasoned that “ Washington compulsory educational law is unconstitutional and the boycott should not be considered illegal.”29

Dr. Earl Miller added to this argument when he claimed that rather than suffer because of the boycott, students would receive “leadership training to [become] a new generation of civil rights leaders.” He thought the efforts that the board had taken to date could be classified as tokenism, and that the boycott was just the beginning of a long term struggle with the school board. Rev. Adams also stated that the boycott was only the beginning.30

The school board, however, continued to virtually ignore the threats of boycott, and the Superintendent’s final word was that the boycott was an “illegal thing:” students participating would receive no disciplinary action but would be given unexcused absences, and “teachers also will be expected to fulfill their teaching contracts on the boycott days.”31 Opposition didn’t end there; Governor Dan Evans did not support the boycott because he saw it offering no solution: “I’d much rather see the talents of civil rights leaders and of the community as a whole working out a solution, rather than protesting a problem.”32 Grace Meur, a citizen of Seattle who submitted her opinion to a Catholic newspaper, took this kind of thinking further by framing her opposition to the boycott as a fear of the kind of direct action that had made southern segregationists so infamous: “The intelligent approach is through the courts. No people like to be ruled by mob-rule, neither here nor in the South.”33

The movement moved to the next step on March 18 when the NAACP filed a suit on behalf of thirty black students. Even though the school board had partially recognized the issue of segregation in the schools, the main issue was whether or not the board had done enough to eradicate it. The suit sought to obtain a court order which would require the school district to submit a plan for the elimination of racial segregation in the schools and specifically asked that Washington Junior High and Mann Junior High—along with. Leschi, Harrison, Colman, and Minor elementary schools— be closed. The suit also sought to put an end to the alleged practices of the districts of drawing school boundaries that caused racial segregation, assigned black teachers on the basis of race, and failed to promote qualified black and other non-white teachers to become principals.34 Earl Miller, NAACP Education Chairman, stated that the boycott could have been avoided if the school board had been receptive to any of the four suggestions they had made: “The only thing we wanted was some tangible proof that the school board was sincerely interested in eliminating segregation in the school system.”35 Miller justified the coming boycott by saying that “We cannot afford to allow the school board to succeed in its policy of containment and isolation of the Negro children on a residential school reservation outside the mainstream of American education.”36

THE BOYCOTT

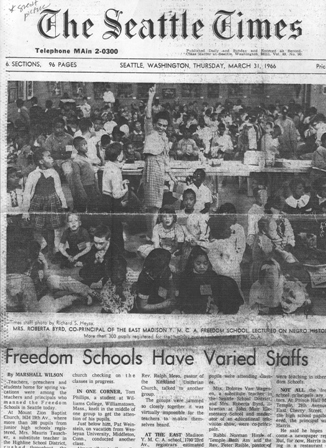

The school boycott was held on March 31 and extended to April 1, 1966. The chairman of the Boycott Committee, Rev. Dr. John Adams, estimated that 3,000 students participated in the freedom schools that were held in lieu of attending regularly scheduled class. The students attending these freedom schools put in a full day from 8am to 3pm; once they were there, they were not allowed to leave.

The overall rates of city-wide school absence were at 10.2 percent. The previous day, the rate was around 6.3 percent. On March 30, the day before the boycott there had been 824 students from school. On March 31, the first day of the boycott there were 3,185 students absent from school. On April 1, there were 3, 918 absent from school. The rates of central area schools were as high as fifty percent. Overall, the increases in the absentee rate over the two days were 58.5 percent.37

Dr. Adams stated that around 30 percent of the students attending the freedom schools were white. This number shows that there were a substantial number of whites who were sympathetic to the plight of blacks in Seattle . For some white students that attended the freedom schools, it was the first time they had gone to schools with blacks.

The teacher absence rates were the lowest they had been since February 14th of that year. Only three district certified teachers participated in the boycott due in part to the district policy on contractual obligations. Dick Warner, a history and economics teacher at Ballard H.S., was one of the three who chose to teach at the MountZion freedom school. He said: “One cannot be an active and responsible citizen without taking action—that’s what I teach my pupils in school. I strongly believe in integrated schools. It is my duty to participate.”38 Participation in the boycott had been much higher than anyone expected.

The turnout at the freedom schools was so overwhelming that crowding became a problem. When a site filled up, the children were sent to another location nearby. Reverend Samuel McKinney of MountZion Baptist Church accommodated 500 children, and noted that “All the facilities we utilized were taxed to capacity. We had to find some auxiliary sites.”39 New freedom schools were needed due to overcrowding and were opened at Temple de Hirsch and St. Clements Episcopal Church. When dropping off their children at the freedom schools, some parents ended up staying because the sites were so crowded. A prime example is Carol Richman, who stayed at the freedom school at Madrona Presbyterian School which was 320 children above capacity.40 As Walter Hundley said, they wanted the entire operation to be carried out “in a manner that really seemed responsible so that the public…would understand that we are serious, and that we are responsible;…and that we were willing to pay our dues for a better system.”41

The students in Seattle had strong opinions regarding the boycott. Barbara Crocker, a sophomore at Garfield , said that “the only way for anything to be done is for us kids to take action.” Kevin Castle, said that “it doesn’t seem like the best plan—this boycott. But it’s the best step taken so far.” Tom Torrance, an eighth grader at Meany J.H. said “We see the problems at school with our colored classmates, probably even more and better than our parents do.” Wendy Peterson, 17, who attended the freedom school because she couldn’t live with herself if she hadn’t, said “I’ve always thought and said I am for integration. I felt if I couldn’t come I couldn’t say I’m unprejudiced.”42

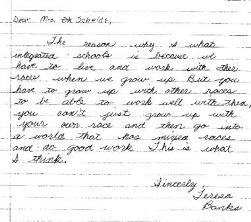

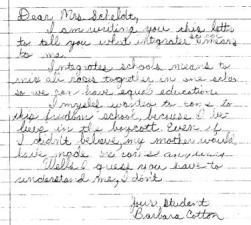

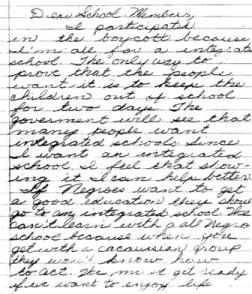

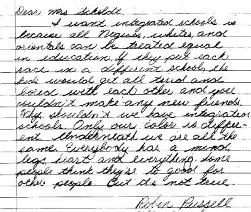

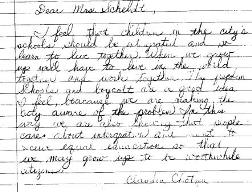

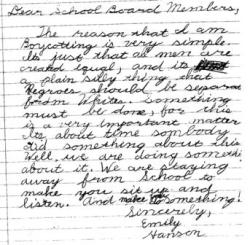

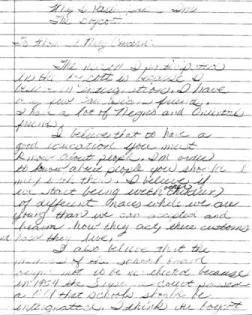

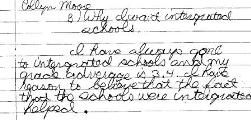

A source that can shed light onto what drove young students to participate in the freedom schools were some letters written by students to members of the school board. There were a limited number of letters, so they are not in any way representative of the feelings of all students who participated. But they do provide a unique lens to look at the experience. One student, Teresa Banks, wrote that she wanted integrated schools because “you have to grow up with other races to be able to work well with them, you can’t just grow up with your own race and then go into a world that has mixed races and do good work.” Deborah Tate wrote that “the only way to prove that the people want it is to keep the children out of school for two days. We can’t learn with an all Negro school because when your get with a Caucasian group they won’t know how to act.” Robin Russell wrote: “Why shouldn’t we have integrated schools? Only our color is different. Underneath we are all the same. Everybody has a mind, legs, heart and everything.” Claudia Chotzen wrote: “The freedom schools and boycott are a good idea. I feel, because we are making the city aware of the problem. In this way we are also showing that people care. About integration and want to receive equal education as that we may grow up to be worthwhile citizens.” Emily Hanson wrote, “It’s about time somebody did something about this. Well, we are doing something about it. We are staying away from school to make you sit up and listen. And make you do something!” Clearly, these students not only expressed their desire to attend integrated schools. They showed the power of certain kinds of protest to engage youth in civil rights movement organizing and even leadership.

THE AFTERMATH

All the sponsors of the boycott considered it a huge success. The School District , in denial, stated that the increase in absenteeism was attributed to the next week’s spring vacation. They maintained that the boycott was not a success and that, based on its total effect on the school system, the response to the event was moderate.

The civil rights leaders thought this was the administration’s attempt to neutralize the effects of the boycott and knew for themselves that it had been “a clear cut success.”43At a news conference on April 1, John Adams called the boycott a “solid success,” and observed that it had “generated the first full-scale discussion of de facto segregation in our community.” He connected the widespread participation in areas inside as well as outside the central area as being large support for integration. Looking back at the initial goal of the boycott, Adams said “…we are now hopeful that the Seattle School Board will develop a master plan to integrate the schools within a reasonable time, perhaps over the course of several years. This has been our objective from the start.”44 A realistic evaluation raises the point that there were practical problems beyond the School Board’s power to overcome. The underlying message in the boycott was for everyone to think about, not just those on the board.

In an unpublished CORE paper, the author of Impressions from a Vice-Principal of one of the freedom schools recounted a phone call from a mother whose children had attended the freedom school. She told him over the phone how overjoyed she was because after coming home her children had a “new sense of pride in being Negro and a new knowledge of the part that Negroes have played in America—obviously something happened that neither she nor her children would ever forget.”45 These African American children experienced something that was truly life changing: they began to understand the important role that African Americans have played in America and learned about their culture. Mineo Katagiri, the Methodist pastor who would later found the Asian Coalition for Equality (ACE), was the parent of one of the freedom school students, and felt the boycott would be a turning point after which the School Board would have to take the civil rights leader’s demands seriously.46

Others did not see the boycott as such a success. Some critics thought that most whites were left unaffected by the boycott and that there was token support from some white families who participated in the freedom schools. Hundley, who had been pleased with the immediate success of the boycott, thought that “the long run result of it wasn’t productive because despite that huge effort, the District really still let us down.”47

But the boycott was not the end of the fight for integration of Seattle ’s public schools. The NAACP’s Dr. Miller announced that several events were planned to follow the boycott. The NAACP tentatively scheduled another boycott for May; planned to file charges with the State Board against Discrimination alleging discrimination in hiring of Seattle school personnel, and asked “to have supervision of the Federal Head Start program given to some other agency because the school has failed to integrate the program.”48 Though the second boycott never took place, the struggle continued.

CONCLUSION

The Seattle Boycott shows the complex and diverse nature of the civil rights movement as a whole. Juan Williams asserted that over ten years, the civil rights movement had transformed that nation as well as a race. After 300 years of oppression, blacks were now given a sense of dignity, power, and citizenship. Whites were changed as well, instead of accepting a segregated society; many began to question how they treated blacks with whom they came into contact with. It would take more than legislation to change the hearts and minds of whites. “After the Selma march, the assassination of Malcolm X, and the signing of the Voting Rights Act, a new sense of injustice began to burn in northern cities.”49 This injustice is what fueled the necessity for a boycott to secure equal education for the children in Seattle . This boycott in Seattle came after those in the South. But it was the fight in these Southern cities that made this boycott in the North possible.

This event highlights the determination and strength of people in Seattle who believed in justice and equality of education. The civil rights movement which had been brewing in places like Selma , and Memphis gave strength and hope to the civil rights leaders in Washington . Their children’s access to a brighter future, without having to be treated as second class citizens, was their ultimate goal. The immense effort in time and planning that went into the boycott was enormous. There should be no question of whether the boycott was successful or not. To organize over three thousand children, in ten freedom schools without a glitch was a success in and of itself. The legacy it has left for the city has been invaluable. It has empowered future generations to strive for change and realize the agency available to them to realize that change. All it takes is the desire and the need to recognize that change is necessary. When Walter Hundley called that meeting in early February of 1966, he was uneasy about the reaction he would receive. But in his heart, he knew something drastic and peaceful needed to be done to bring everyone attention to the gross inequality that was taking place. The boycott could not have been accomplished without the help of the hundred of planners, teachers, acting principals, parents, and students involved. The whole community really pulled together to make it happen.

The boycott that took place in Seattle was much like the boycotts that have taken place in other parts of the country and around the world. Segregation and unequal treatment have not only affected African Americans. This paper has focused on the unique history of African Americans in this country, but people of color and immigrants have been subject to second class treatment since before this nation even was called America . The hope for equal education still has yet to be realized, as integration rates today are decreasing and segregation is becoming more common. The gains that blacks made as a result of the civil rights movement are slowly being taken away. We are seeing a quiet, slow reversal of the Brown v. Board Supreme Court ruling. The end of mandatory bussing and the attacks from the right wing on voluntary affirmative action programs in some states have been big setbacks in the quest for achieving equal educational opportunity for blacks comparable to their white cohorts. Looking into the past should give this and future generations the hope and the desire to see change come to pass. The Seattle Public School boycott is just one example of a method of direct action to make the people in power listen and act accordingly.

**© Brooke Clark 2005

**HSTAA 498 Fall 2004

This paper won the UW History Department’s York-Mason prize in 2005. It was republished in the Feburary, 2006 issue of ColorsNW Magazine.

1 Seattle Times, August 15, 1965

2 “Fact Sheets on the Schools,” CORE papers

3 STA NEWS February 1966 p. 5

4 UW CORE. “ Seattle Civil Rights Groups Feel Boycott Only Way to End Segregation”

5 The Urban League, A Proposal for Reorganizing the Elementary Division of the Seattle Public Schools. Autumn, 1964, p.1 Mimeographed pamphlet, Seattle Urban League as quoted in Larry S. Richardson, “Civil Rights in Seattle : A Rhetorical Analysis of a Social Movement” Ph.D dissertation, Washington State University , 1975) p.158

6 Jeffrey Gregory Zane, “ America , Only Less So? Seattle ’s Central Area, 1968-1996” (Ph.D dissertation, April 2001) p. 90

7 Richardson , “Civil Rights in Seattle ,”p. 159

8 Seattle Times, May 13, 1965 p. 53

9 “Freedom Schools Planned for the Boycott” by Lane Smith, newspaper unknown

10 The Corelator February 20, 1966 p1

11 Seattle Times, May 5, 1965, p. 19

12 Seattle Times, May 5, 1965, p. 19

13 Seattle Times, May 6, 1965, p. 41

14 Seattle Times, March 18, 1966

15 Hundley interview, February 13, 1975 as quoted in Pieroth, Dorothy Hinson. Desegregating the Public Schools Seattle , Washington 1954-1968. UW PhD Dissertation-History, 1979. p. 252

16 UW. Copy of Letter to Seattle Public School Officials Concerning Civil Rights groups School Boycott March 31 and April 1, February 23, 1996

17 UW. CSCC 7-Seattle Public Schools: “Copy of Letter to Seattle Public School Officials Concerning Civil Rights Groups’ Boycott March 31 and April 1,” February 23, 1966 as quoted in Pieroth p. 254

18 Seattle P-I, February 23, 1966, p. 25

19 Seattle Times, March 25, 1966

20 Seattle P-I, February 23, 1966, p. 25

21 http://www.core-online.org/history/freedom_summer.htm

22 “Freedom Schools Planned for Boycott” by Lane Smith

23 UW CORE; 2 Minutes, 1963-66: Minutes of general meeting, March 24, 1966 as quoted in Pieroth

p. 256, Seattle Times, March 6, 1966.

24 Seattle Times, March 25, 1966.

25 Seattle P-I, March 27, 1966 p. B

26 Seattle Times, May 5, 1965, p. 19

27 Seattle Times, March 20, 1966

28 Seattle P-I, March 27, 1966

29 Seattle Times, March 31, 1966

30 Seattle Times, March 30, 1966

31 Seattle Times, March 30, 1966 p. 8

32 Unknown newspaper March 22, 1966

33 _The Progress,_ March 25, 1966 p5

34 Seattle P-I, March 19, 1966 p. 4

35 Seattle Times, March 2, 1966 p. 8

36 Seattle Times, March 31, 1966, p. 1

37 The Facts, April 7-14, 1966 p. 4

38 Seattle Times, April 1, 1966

39 The Facts, April 7-14, 1966 p. 4

40 The Facts, April 7, 1966, p.6

41 Hundley interview, February 8, 1978 as quoted in Pieroth p.276

42 Seattle Times, April 1, 1966 p. 1

43 Seattle P-I, April 1, 1966, p. 1

44 Seattle P-I, April 3, 1966, p. A

45 UW CSCC: CORE papers-Unpublished

46 Katagiri interview, June 19, 1973

47 Christian Science Monitor, April 18, 1966. p13

48 Seattle P-I, April 1, 1966 p. A

49 Juan Williams, Eyes on the Prize: America ’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965( New York, 1987) p. 287