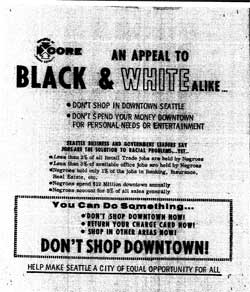

“Don’t shop downtown now! Return your charge card now! Shop in other areas now!” urged leaflets distributed by the Seattle chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), in regards to a boycott fighting employment discrimination.1 Numerous stores in Seattle such as Nordstrom, Bon Marche, Safeway, and J.C. Penny refused to hire black workers in the early 1960s. The situation in Seattle was a microcosm of the widespread job discrimination against African Americans throughout the entire United States. The civil rights movement saw the formation of various civil rights groups that held demonstrations and carried out campaigns protesting the lack of equal rights for African Americans. While some operations were extremely successful and others had a limited impact, the actions taken by civil rights activists exposed the blatant discrimination by whites against minority groups. This essay looks at one of the campaigns undertaken by the Seattle chapter of CORE in an effort to gain more jobs for African Americans in the downtown retail core of the city. The project, called the Drive for Equal Employment in Downtown Seattle (DEEDS), was one of the most extensive and challenging campaigns ever taken on by CORE, and while the results fell short of expectations, DEEDS opened the eyes of many Seattleites to the crucial issue of employment discrimination.

In the spring of 1942, CORE, a civil rights organization dedicated to gaining equality for African Americans through the use of nonviolent means, was established in Chicago. Of the six founding members of CORE, four were divinity students and two were liberal arts students; all had been engaged in the Christian-pacifist movement of the 1930s.2 According to historians August Meier and Elliot Rudwick, members of CORE “were required to be well versed in the principles of nonviolent philosophy, to be active in some phase of CORE’s work, and to accept the ‘Action Discipline’ which set forth the modified Gandhian methods by which CORE operated. Commitment and dedication were deemed more important than size.”3 A focus on democracy, one of the main tenets of CORE’s philosophy, played an important role in the operation of the organization, as elections took place every two or three months. The leaders of CORE strongly emphasized nonviolence, and the Action Discipline stated that a peaceful approach “confronts justice without fear, without compromise, and without hate … it is suicidal for a minority group to use violence, since to use it would simply result in complete control and subjugation by the majority group.”4 Interracialism was another important aspect of CORE’s ideology. The group saw discrimination against African Americans not as a racial problem but as “a human problem which could be eliminated only through the joint efforts of all believers in the brotherhood of man.”5 Using this philosophy, in its first year of operation, Chicago CORE successfully fought discrimination at a roller-skating rink, a barbershop, the University of Chicago, and at restaurants throughout the city. Other CORE chapters throughout the country began to form, and by 1947 thirteen branches, located primarily in the Midwest, had been established.6 The majority of CORE members, both blacks and whites, were young, educated men and women from middle-class families. In the 1940s, CORE chapters achieved modest successes in restaurants and areas of recreation, but negotiations in the school and housing sectors generally failed. Despite these early disappointments, CORE continued to increase in members and chapters throughout the country and many campaigns fighting discrimination gained momentum.

The 1960s saw significant improvements in the tactics used by CORE as well as their members’ level of participation and influence within the civil rights movement. The largest and most successful campaign undertaken by CORE was the Freedom Rides of 1961 in which men and women challenged segregation on interstate buses, bus terminals, and in all-white dining rooms throughout the South. The impact of the Freedom Rides was felt throughout the United States. As Meier and Rudwick argue, it “not only had a momentous impact on the patterns of southern segregation; it also exerted an influence impossible to exaggerate upon the civil rights movement itself.”7 Following this major CORE campaign, many of the smaller chapters were inspired to take on further non-violent action against discrimination in housing, education, and employment. The national office offered chapter leaders training and workshops in order to provide experience and knowledge in how to organize local campaigns.8 More CORE chapters continued to form, and as of 1961 there were 53 active chapters—one of which was located in Seattle, Washington.

Despite not being established until twenty years after CORE was founded, the Seattle CORE chapter quickly gained high levels of participation and undertook many significant and influential projects in the 1960s. Joan and Ed Singler, two of the founding members of the Seattle CORE branch, saw the CORE Freedom Rides on television and were inspired to join the movement against segregation.9 Formed in July of 1961 with approximately thirty active members, Seattle CORE was evenly integrated, with about half African Americans and half whites. In order to be an official member, individuals had to attend an orientation, commit to non-violence, and participate in role-playing sessions as well as actual demonstrations. 10 Seattle CORE’s first major operation in 1961 involved “selective buying campaigns,” which targeted employment discrimination in businesses such the Bon Marche, J.C. Penny, Nordstrom, Frederick and Nelson, and the A&P Grocery chain. CORE’s tactics involved picketing and “shop-ins,” in which protestors filled shopping carts with merchandise and once the cashier had rung up the items, left the store without paying.11 These protests resulted in the hiring of a small number of African Americans at local department stores and supermarkets by the end of 1963. Seattle CORE launched a second campaign in 1963 focused on housing discrimination, as members tried to expose the racism in the Seattle housing market. One tactic involved over 200 people picketing at the Washington Real Estate Board during a three-day period.12 For many members of CORE, the organization was a way of life in the early 1960s. As Joan Singler recalled, “every part of our life was totally committed to doing CORE activities.”13 CORE members spent endless hours together planning protests and demonstrations, researching, fundraising, training, and even cooking. The enormous amount of time and dedication put in by the activists was reflected in the continual growth of the Seattle chapter as well as in the increased number of campaigns targeted at ending racial discrimination.

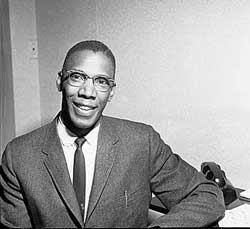

As of May 1964, the Seattle CORE branch had 139 active members in addition to a variety of elected leaders. Walt Hundley, one of the chairmen of the chapter, held a master’s degree in social work from the University of Washington.14 Born in Philadelphia, Hundley moved to Seattle in 1954 to work as a minister at the Church of the People and after several years became involved in social work. Not only did Hundley preside as chair of Seattle CORE beginning in November of 1964; he was also a member of the Central Area Civil Rights Committee and organized numerous demonstrations throughout Seattle.15 Charles and Bettylou Valentine were also extremely active members of Seattle CORE and helped promote and research various projects undertaken by the organization. Charles, a professor of anthropology at the University of Washington, wrote two extensive studies regarding the segregation of African Americans in Seattle. His wife, Bettylou, a graduate student at UW, volunteered as the secretary for Seattle CORE and recorded the minutes for weekly meetings. While she wanted to eventually become the chair, women were discouraged from running for president and instead headed smaller committees; Joan Singler chaired the housing committee, and Jean Adams ran the negotiating committee.16

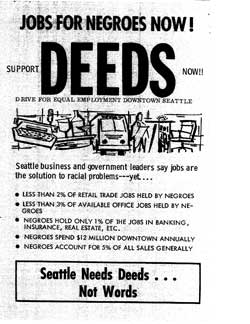

In the summer of 1964, Seattle CORE undertook a major campaign in downtown Seattle with the goal of attaining over a thousand well-paying jobs for African Americans. Over the years, despite numerous negotiations with various businesses attempting to put an end to employment discrimination, only a small number of blacks had been hired for white-collar jobs.17 While they had made modest gains, members of CORE wanted to see a more notable change in the hiring practices of retail stores, restaurants, and offices throughout downtown Seattle. On a national level, Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned employment discrimination in the United States. Specifically, Title VII made it unlawful for an employer “to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual … because of such an individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”18 Therefore, in theory, companies and organizations in Seattle should have been hiring an increased number of African Americans; however, in reality, the Civil Rights Act did not generate many immediate changes. At a weekend seminar held by CORE in May of 1964, members addressed the difficulties in achieving success in the realm of employment discrimination and made various suggestions about how to overcome these obstacles. In past campaigns CORE had usually dealt with one employer at a time instead of approaching a large number of companies at once, which members recognized as a significant problem.19 During a CORE membership meeting on June 9, 1964, Walt Hundley announced a proposal to create a campaign against employment discrimination that involved a widespread boycott of the entire downtown area. Following a great deal of discussion, Hundley made a motion that CORE establish “a project committee to investigate the idea of a downtown boycott with no action to be taken without a definite mandate from the membership and that the investigation include at least surveying of Central Area interest, a survey of downtown businesses, and mobilization of Negro, white and other organizational support.”20 Hundley’s motion passed with thirty-six votes in support, none opposed, and two abstentions, and a team was established to perform surveys and research regarding demographics and employment practices in downtown Seattle.

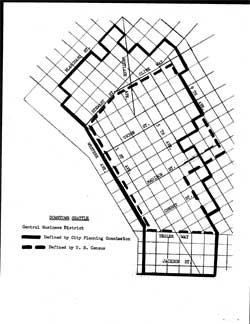

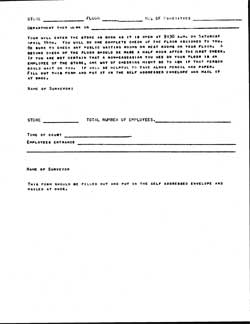

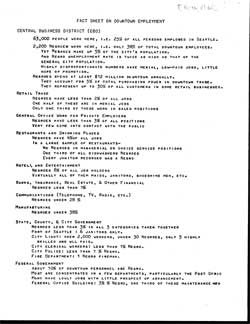

A committee of approximately thirty CORE members completed a substantial amount of research in June and July of 1964 in order to generate a solid basis of information on which a boycott of downtown Seattle could be enacted. The volunteer study team – made up of social scientists, university students, high school students, housewives and skilled downtown employees – and led by Charles Valentine, included both African American and white members.21 The primary purpose of the study was to learn about the role of African Americans as downtown consumers, the availability of jobs in the downtown area, and the feasibility of increasing the number of African Americans in the work force without the displacement of any current employees. As there was no existing data regarding employment practices in the 1960s in Seattle, CORE had to directly collect most of its information. The CORE committee primarily approached the study by conducting extensive surveys in the downtown area. Twenty-four individuals conducted the surveys in four phases during the summer months of 1964. 22 The first phase was the retail employment survey, which involved recording the ethnicity of all observable employees in the twenty square blocks of the most intensive retail core of the downtown area. Over 200 businesses with 1,300 employees were surveyed, with the majority being department stores, apparel shops, drug stores, hardware stores, restaurants, and hotels.23 The second phase involved a survey of private offices in eight major office buildings located between 2nd and 4th Avenues and Pike and Jefferson Streets; information on a total of 9,000 employees was recorded.24 The third phase was a survey of all downtown government workers, including those in the federal, state, county and municipal offices. Surveys in the Federal Courthouse, Federal Office Building, King County Courthouse, Municipal and Public Safety Buildings, and City Light counted 3,650 government employees.25 Finally, the fourth phase included a customer survey of all retail stores, which involved observing customer entrances and recording the ethnicity of each shopper as “white,” “Negro,” or “nonwhite.” The members of the CORE team performed the surveys in one to three hour time blocks, usually during heavy shopping periods. In all, 6,650 customers were observed and recorded.26 While the committee was unable to survey every business or office in the downtown area, they were able to cover between 25 and 50 percent of all employees. The study team consulted various professional statisticians, demographers, and economists at the University of Washington in order to make more productive use of the information they obtained. One major problem the members of the CORE team noticed during the downtown surveys was that a majority of African American workers were employed in menial positions hidden from the public eye, such as night janitors or dishwashers. Consequently, the surveyors found it difficult to accurately determine the number of African Americans employed in downtown Seattle.27 Despite this setback, the Seattle CORE committee was able to collect a significant amount of data that proved to be extremely useful in understanding the widespread employment discrimination problem in the downtown area.

The statistics and information compiled by the CORE study team revealed a significant under-representation of African Americans employed in downtown Seattle in comparison with the number of African Americans living in the city. At the time of the study, 28,000 African Americans lived in Seattle, which accounted for 5 percent of the total population; 75 percent of Seattle’s blacks lived in nine census tracts in the Central Area.28 The CORE surveys revealed that while African Americans were 5 percent of the city’s population and made up 5 percent of downtown retail consumers, they held less than 3.5 percent of downtown jobs.29 Of the 55,000 jobs provided by private employers downtown, African Americans held only 1,600 (less than 3 percent). What is more, a majority of the positions African Americans did hold were as janitors, hotel maids, kitchen workers, night maintenance employees, and other less desirable, unskilled, and poorly paid occupations.30 In the downtown retail sector, less than 2 percent of all jobs were held by African Americans and, of those positions, less than a third were sales jobs and only 10 percent were in an office.31 The statistics in the clerical and general office sector in downtown Seattle exposed even greater employment discrimination: of the 9,000 jobs in ordinary office buildings, only 18 African Americans were observed, which is 0.2 percent of the total positions.32 When the CORE team surveyed 2,000 restaurant workers in 65 establishments, they did not find a single African American working as a manager, hostess, cashier, or even waitress, but they observed that every restaurant had an African American janitor.33 The under representation continued: only 1 percent of jobs at banks and real estate offices and less than 1 percent of jobs in municipal government were held by African Americans. Only three African Americans were observed among the 550 employees at the King County Courthouse.34 In terms of customers, the committee found that African Americans made up 12 percent of shoppers in retail stores, which they determined was most likely due to the close proximity of the Central Area to downtown Seattle along with the lack of stores in the Central Area.35 The study also estimated that African Americans controlled 4 percent of the total purchasing power and spent between $12 and $26 million per year in downtown Seattle.36 In addition, CORE found that in the month of June 1964, the turnover rate of jobs was 0.7 percent of the total work force, which included 251 new hires in the retail and financial business sectors.37 When these numbers were applied to the entire downtown area, the CORE team determined that downtown employers would make a minimum of 5,350 new hires over the next year, which averaged out to about 450 people added to the payrolls each month.38 With all these statistics exposing the significant employment discrimination problems faced by African Americans in downtown Seattle amid the continual opening of new jobs, the Seattle CORE branch decided to charge ahead with the planned boycott of the entire downtown area.

The Seattle CORE employment campaign and eventual boycott of the downtown area, officially known as DEEDS, set up detailed goals of exactly how many African Americans were to be employed downtown and specific dates of when these goals must be met. These goals were first announced in a June 24th letter sent to downtown private and government employers from the Seattle CORE chairman and the chairman of the Central Area Committee on Civil Rights.39 The proposed goals of the DEEDS campaign were as follows:

- I. That 1,200 Negroes, in addition to those presently working in downtown Seattle, be employed in that area by 1 February 1965.

- II. That this total of new hires be achieved over a period of six months in stages marked by three steps: A. Negroes placed in 300 positions by 1 September 1964. B. Negroes placed in 400 additional jobs by 1 November 1964. C. Negroes hired in 500 more jobs by 1 February 1965.

- III. That the total of new hires be broken down in six employment categories: A. Office work for private employers: 200 positions. B. Sales and related jobs in retail businesses: 250 positions. C. Positions in bank and other financial concerns: 200 jobs. D. Jobs in hotels, restaurants, and entertainment: 100 positions. E. All levels of government employment: 250 posts. F. Manufacturing and other categories: 200 jobs.

- IV. That both in new hires and in promotion of present employees, Negroes receive a large share of the more desirable positions, using where necessary special measures such as: A. Intensive recruiting in the Negro community. B. Extensive publicity that applicants of all races are sought. C. Explicit instructions to all employment agencies. D. Intensive use of the employment services of civil rights groups. E. Immediate promotion of present Negro employees to better positions. F. Employer-financed programs to increase the skills of both present and prospective Negro workers. G. Placement of present Negro employees and new hires in contact with the public.40

While these goals were not intended as strict demands to fill racial quotas, they provided CORE members with an overall objective to strive towards in the latter half of 1964. The DEEDS program was broadcast at various times and locations in letters, posters, and leaflets throughout the city of Seattle, laying the groundwork for one of the most ambitious employment campaigns ever carried out by a CORE chapter.41

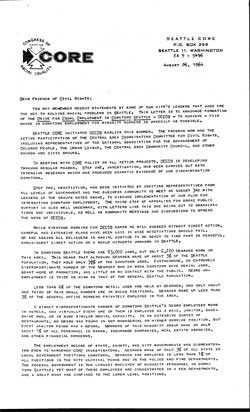

In August of 1964 the first major step of the DEEDS campaign began, which involved negotiations between representatives of downtown employers and members of CORE. Both public and private employers, representing a large area of downtown Seattle, attended the negotiations. The first meeting took place on August 3, 1964, at which representatives of DEEDS requested that employers take a census of present and prospective job openings and asked for suggestions on how to effectively reach their employment goals.42 Tim Martin, the current chairman, and Charles Valentine spoke on behalf of CORE, John Adams represented the Central Area Coordinating Committee on Civil Rights, and Charles Johnson spoke for the NAACP. During the negotiations, only the spokesmen for the federal government and Seattle Mayor J.D. Braman expressed a willingness to hire more African American workers; no other employer agreed to discuss the goals of DEEDS.43 Following the first meeting, Seattle CORE mailed another letter to downtown businesses threatening direct action if no workable plan was implemented by the first of September. The letter stated that no real conclusions were reached in the first round of negotiations and requested that representatives of downtown employers come to the next meeting on August 17th with “a concrete proposal describing how the existing plan can be implemented in his branch of government or sector of industry.”44 A list of cooperating organizations was contained in the letter, which included CORE, the Central Area Coordinating Committee for Civil Rights, the Seattle NAACP, the Baptists Ministers Alliance, the Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs, the Central Area Community Council, and the Greater Seattle Council of Churches. Several weeks of negotiations followed without any significant proposals by downtown employers to hire more African Americans; thus, the second phase, that of appealing to broad public support and implementing direct action, began.

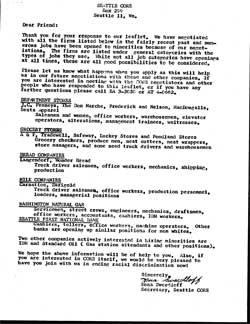

The DEEDS campaign was not Seattle CORE’s only project as of August 1964, and in fact CORE was working on a variety of other activities throughout the duration of DEEDS. In the latter half of 1964, CORE prioritized four main issues: employment, education, housing, and fundraising. In the employment sector, not only did CORE members put a tremendous amount of effort into the DEEDS project, but they also continued employment negotiations with a wide variety of companies, unrelated to DEEDS activities. These businesses included Darigold, Carnation, A&P, Safeway, Wonderbread, J.C. Pennys, Rhodes, Bon Marche, Frederick & Nelson, Nordstrom, Washington Natural Gas, and Greyhound.45Focusing on education discrimination, CORE was in the process of presenting short-term and long-term plans for integrating local schools. Housing was another important area for CORE activists, and during August 1964 CORE carried out an “intensive investigation into possibilities for a rent strike against slum conditions in some parts of the Central District.”46 Finally, CORE put on various fundraisers such as a CORE dance to earn money for community education. Overall, CORE was an extremely active and efficient organization that was able to manage numerous activities at once and to effectively fight racial discrimination in different fields. While Seattle CORE members had many projects to handle in 1964, none required as much manpower as DEEDS, which was quickly developing into a significant and extensive campaign.

The first step of reaching out for public support of the DEEDS campaign involved spreading the news about the project to local communities and informing people about how they could get involved. On August 26, 1964, Tim Martin sent a letter to members of various Seattle civil rights groups describing the DEEDS project and asking for cooperation from African Americans as well as whites living in Seattle. This letter was the first public announcement of DEEDS. It detailed the severe employment discrimination in downtown Seattle and explained that African Americans held only 2,200 of the 63,000 jobs in the downtown area.47 Martin requested that individuals contribute to the campaign by informing friends and organizations about the project, encouraging minorities to apply for employment downtown, promoting fair hiring practices, and, if necessary, engaging in non-violent direct action. Along with the mass mailing of the CORE letter, members distributed approximately 15,000 leaflets explaining the DEEDS campaign in the Central Area community in late August and early September.48 CORE activists also held local neighborhood meetings throughout the Central Area to inform people about DEEDS. At a CORE membership meeting on September 8, 1964, members decided by a vote to discontinue negotiations with individual downtown employers and instead focus entirely on the direct action campaign.49 Local support for the DEEDS campaign grew as a result of the letters, leaflets, and meetings, and the framework for a boycott of the entire downtown area began to take shape.

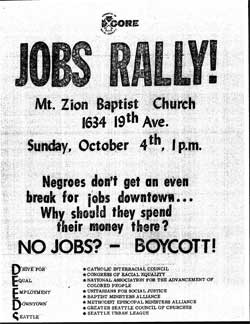

October 1964 witnessed the launch of the direct action phase of the DEEDS campaign in the form of non-violent boycotting, leafleting, and picketing. The first goal of the DEEDS project had been 300 jobs for African Americans by September 1st. Yet as of the beginning of October, no jobs had been offered to blacks.50 A kickoff rally took place on October 4th, which marked the start of the boycott of the entire downtown retail area. The rally occurred on a Sunday at 1 p.m. and was held in the parking lot of the Mt. Zion Baptist Church, a predominantly black church that had been the site of a visit by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. three years earlier. Members of CORE wanted this rally to be “a public witness of our commitment to civil rights,” and the rally was sponsored not only by CORE but also groups such as the NAACP, Catholic Interracial Council, Unitarians for Social Justice, Baptist Ministers Alliance, Seattle Urban League, and the Greater Seattle Council of Churches.51 The boycott targeted all businesses in downtown Seattle, including department stores, smaller retail shops, restaurants, and movie theaters. CORE decided to implement the boycott during the holidays, the busiest shopping period of the year, in order to create the largest impact on the sales of the hundreds of downtown businesses, many of which depended on high revenues at the end of the year in order to make their yearly profits.

Various CORE chapters throughout the country used the tactic of a boycott as a primary method of non-violent protest. Following the end of Great Depression, American business began to flourish, fueled by the public’s powerful new role as consumers; consequently, as Kathy M. Newman writes, “the new promise of mass consumption made the civil rights boycott a more effective tool in the fight against discrimination.”52 One of the first instances of boycotting took place in the 1930s when African Americans implemented “Don’t Shop Where You Can’t Work” campaigns in cities such as Harlem, Baltimore, and Los Angeles. These protests called for African Americans to decline to shop in businesses that refused to employ blacks as a way to peacefully urge companies to change their hiring practices. One of the most famous civil rights actions, the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, involved African Americans refusing to ride the city buses for over a year and eventually achieved the desegregation of public transportation in Montgomery. Inspired by the success in Alabama, members of CORE employed numerous boycotts to fight widespread employment discrimination across the country. In Omaha, Nebraska, a CORE chapter boycotted a local Coca-Cola plant for six weeks in 1951 and gained several jobs for African Americans; several years later, the same branch boycotted an ice cream parlor, which resulted in the hiring of a black saleswoman.53 The Los Angeles CORE implemented a boycott of a beer company in 1961 and 1962, gaining jobs for three black salesmen. Similar successful boycotts took place in cities such as Berkeley, Washington D.C., and Boston, reflecting the substantial influence a boycott can have on the practices of businesses. As the majority of the CORE boycotts were limited in their scope and size, the Seattle CORE’s DEEDS campaign proved to be one of the largest and most demanding boycotts ever carried out by the organization.

Following the commencement rally, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce promised to hold a “Jobs Fair” on Saturday, October 17th. CORE demanded that a minimum of 200 jobs be offered to African Americans at the fair, and William Adams, the executive vice president of the Chamber, agreed to this requirement. However, Adams later postponed the “Jobs Fair” indefinitely, further frustrating the Seattle CORE members.54 As a result of the postponement of the fair, at a CORE membership meeting on October 13, 1964 Walt Hundley proposed a motion that “CORE call a special meeting Saturday which would conduct a leafleting of the Central Area and demonstrations downtown to include leafleting at bus stops and a roving picket.”55 According to Hundley, this meeting needed to have at least 50 participants or it would be cancelled. The motion passed with over 40 votes in support, two abstentions and none opposed. As planned, the meeting took place on Saturday, October 17th with the participation of 70-100 Methodist students and involved leafleting the Central Area to inform people not to shop downtown. Furthermore, on Monday, October 19th from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. CORE members began demonstrating downtown. The demonstrations included a roving picket and the leafleting of major downtown bus stops.56 CORE had strict rules regarding picketing, requiring that men were clean-shaven and women did not wear slacks. No one in the picket line was allowed to engage in long conversations or block the sidewalk. Most importantly, CORE stressed that no one was to respond to verbal or physical harassment in order to keep the picket line free of violence.57 Seattle CORE members and DEEDS participants hoped their demonstrations would attract the attention of employers and create a significant decrease in sales for downtown businesses in order to secure their goal of 1,200 jobs for African Americans.

In the latter half of October 1964, with the DEEDS campaign still struggling to secure any jobs for African Americans, CORE decided to continue with the demonstrations and boycott of the downtown Seattle area. In a memo sent from CORE on October 23, 1964, the failure of downtown employers to take positive steps towards putting an end to employment discrimination was reemphasized along with a request for Seattleites to not shop downtown. The memo stated that “CORE wishes to emphasize that the downtown area symbolizes the job inequality of the entire Seattle employment complex, and demonstrations will continue until jobs for Negroes are offered from those industries in … the stores, restaurants, and businesses in the downtown retail core.”58 More downtown picketing and leafleting took place on Saturday, October 24th and Monday evening, October 26th. One of the leaflets handed out by DEEDS activists, titled “An Appeal to Black & White Alike,” urged people to boycott the downtown area by not shopping there for personal needs or entertainment purposes. It also demanded that people return their downtown store credit cards and shop in other areas of the city.59 Another poster created by CORE and spread throughout the Central Area asked individuals and their children to boycott downtown Seattle until jobs were opened and CORE announced success, which could be through the Christmas season if necessary. The poster explained that people could ride the Freedom Bus, a free bus provided by CORE that ran every hour from 23rd & Union, to other areas for their shopping needs, or they could use the No. 4 bus from 23rd & Madison to the University District. The poster urged readers that, while the boycott might be inconvenient and there would be sales to lure them back to the downtown area, the boycott would work if African Americans stood firm and continued to shop elsewhere.60 As a result of the picketing and leafleting downtown on October 19th, 24th and 26th, Ernst Hardware Stores hired its first African American employee, which marked the first recorded job gained as a result of the DEEDS campaign.61 Further demonstrations took place on Saturday, October 31st and Monday, November 2nd as well as Sunday, November 1st to picket and distribute boycott leaflets. While the members of the DEEDS project had not reached their second goal of an additional 400 jobs by November 1st, they felt more optimistic as a result of the Ernst announcement as the campaign headed into November.

While Seattle CORE stated that it had the support of various civil rights groups for the DEEDS campaign, a Seattle Times article questioned that level of support and assistance. In an article published on October 25, 1964 and headlined “Civil Rights Groups Indorse CORE Jobs Drive, but Not Boycott,” the author explained that “CORE’s intention to boycott business comes at a time when the Chamber of Commerce has instituted a program to increase equal employment opportunities for members of minority groups.”62 The article quoted an observer who said that although CORE may have good intentions and good goals, it lacks support. The author also claimed that while the major civil rights groups support the DEEDS campaign, they were not participating in the boycott, and quoted one civil rights leader saying that CORE had a “tiger by its tail.” According to the article, many of the civil rights groups still had faith in the Chamber of Commerce to help remedy the employment discrimination problem in Seattle.63 This article contradicted the posters and leaflets spread by CORE, which list six or seven participating civil rights groups in the boycott, and raises the idea that CORE was carrying out the boycott of the downtown area without support of other major civil rights groups.

The month of November saw the continuation of the DEEDS campaign, including the tactics of boycotting the downtown area and spreading leaflets around local communities. The November issue of CORElator, CORE’s monthly newsletter, reported that the most effective time for a boycott was during the Christmas season. The CORElator stated, “If we mean to accomplish anything for our children and grandchildren then let’s rededicate ourselves to making the boycott a success. Everyone has the Friday after Thanksgiving off. Everyone should be on the picket line that Friday. When you are called, tell the caller that you will join the line. And we mean NOW!”64 The CORElator also urged readers to get “don’t shop downtown” lawn signs and bumper stickers to spread the message of the boycott. CORE sent a letter on November 16, 1964 to 10,000 supporters of the DEEDS campaign, reminding everyone to stop shopping downtown and take the Freedom Bus, private cars, or public transportation to other shopping areas in the city. The letter explained that individuals should shop at University Village, Greenwood, the University District, Northgate, White Center, Renton, or Burien instead of downtown. Enclosed with the letter was a pledge card, which stated the DEEDS Pledge: “I promise to support DEEDS by refusing to shop downtown until DEEDS goals are met (1,200 jobs for Negroes in downtown area) and to shop in other areas.”65 CORE requested that everyone who supported DEEDS fill out the pledge cards and return them to the CORE office in order to let the downtown employers know what they were up against.

Individuals returned large numbers of pledge cards requesting more information, wanting to donate money, and pledging not to shop downtown.66 A collection of approximately 200 returned pledge cards are stored at the Special Collections Division of the UW Libraries and provide a glimpse into the wide variety of DEEDS supporters. Most of the people who filled out the cards lived in the Central District, with several others living elsewhere in Seattle as well as Bellevue. On about half of the pledge cards people wrote the profession they would like to have in the future; these jobs included doctor’s assistant, dishwasher, diesel mechanic, elementary school teacher, retail clerk, hotel bellman, truck driver, maid, and custodian. Women filled out a substantial majority of the cards, and very few listed highly skilled or well-paying professions. While it is difficult to determine whether these supporters were white or black, it can be deduced based on the large number of addresses from the Central District that many were African American. However, as one pledge card read, “I am white and I am employed but I want to know what I can do to make DEEDS a success.” From cards such as this one, it is clear that DEEDS had the support of at least a minor part of the white population of Seattle.67 Overall, the returned pledge cards provide a picture of the high level of backing from hundreds of individuals throughout the Seattle area as the Christmas shopping season drew near and the news of the boycott continued to spread.

In the final month of the year, the DEEDS project reported limited success in regards to the campaign to end employment discrimination. Nevertheless, CORE remained optimistic. The December CORElator reported, “Seattle CORE’s DEEDS Project is really rolling under a full head of steam. The pickets, car-top parades, signs, occupant mailing, etc are all starting to develop into a real effective boycott of the downtown area. And your support, by not shopping downtown, is beginning to bring about some tangible results.”68 These results included the active recruiting done by the city for non-white personnel for the police and fire departments, as well as decreased sales downtown. The Equal Opportunity Center, which was a center for employment counseling opened by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce in the Central Area in mid-October, was being regularly advertised on television.69 At a CORE membership meeting on December 9th, 1964, Bettylou Valentine proposed and passed a motion that the “DEEDS Committee and Executive Board get back into the negotiations with the downtown people before January 12th.”70 Seattle CORE chairman Walt Hundley sent a letter on December 29th, 1964 to downtown employers requesting a meeting on January 11th with DEEDS representatives. The letter attributed declining sales in downtown stores to the DEEDS boycott but stated that the goal of 1,200 jobs for African Americans has not been remotely accomplished; only 25 downtown positions had been filled by African Americans as of late December 1964.71 Hundley claimed that the downtown businesses had made only a minimal effort toward hiring black workers and only in industries such as trucking and light manufacturing were jobs beginning to open. In a closing summary of the DEEDS campaign in the January 1965 CORElator, the newsletter stated, “the boycott of downtown Seattle that CORE spearheaded over the past few months was quite successful … business was horrible. Believe us, and believe in yourself. You are the people who helped to put it over. And it’s beginning to have some miniscule results.”72 After the end of the holiday shopping season, the nearly three-month long direct action phase of the DEEDS campaign neared its end, but not before one final round of negotiations with downtown employers.

During the negotiations held on January 11th, 1965 members of CORE and the representatives of downtown employers had different views of the results of the DEEDS campaign. The Seattle Times reported that the two sides did not agree on the employment statistics. While CORE’s chairman Walt Hundley claimed that only 25 jobs had been filled by African Americans as a result of DEEDS, James Shelver, the representative for Pacific Northwest Bell, said his firm alone had hired at least 25 African Americans in the past several months. William Adams, the executive vice president of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, said he could account for the hiring of about 100 African Americans and asked for support from CORE for the Chamber’s “Jobs Fair” on January 22nd and 23rd to promote the hiring of black workers.73 Hundley stated that the African American community was unaware of these numbers and thus would continue pressuring downtown employers. During a CORE membership meeting on January 12th, 1965, Ed Singler moved that the “action phase of DEEDS known as the boycott of the entire downtown Seattle area be suspended and a new action be initiated directed at a specific company or industry involving standard CORE procedures.”74 The motion passed and thus, on January 12th the DEEDS campaign, including the boycott of downtown Seattle as well as the picketing and leafleting, came to a close.

In the February 1965 issue of the CORElator, Charles Valentine reflected on the DEEDS campaign and what it had accomplished for African Americans living in Seattle as well as what important questions still remained for civil rights as a whole. Valentine stated that while the downtown boycott was suspended on January 12th, the DEEDS project “reached more people in Seattle than ever before. This was done by … an occupant mailing to 10,000 families in the Central Area, intensive discussion with hundreds of people in small neighborhood meetings, yard signs like those used in political campaigns, auto caravans with car top signs, a public rally, leafleting, and picketing.”75 He also applauded all the time and effort put in by members of CORE as well as local friends and supporters. Valentine acknowledged the fact that other Seattle civil rights groups did not support the boycott, and the only groups other than CORE that aided in the boycott were the Unitarians for Social Justice, the Shipscalers Union, and the Teachers Union.76 The successes of the DEEDS campaign included the large number of individuals who did not shop downtown during the holiday season, which contributed to Seattle businesses’ declining sales in comparison to previous years. Also, Valentine reported that the federal government was helpful in agreeing to and meeting the goal of hiring more African American workers. However, most other employers were not nearly as cooperative in the negotiations with DEEDS representatives and were not willing to comply with the aims of the campaign. Since the beginning of the DEEDS project, the Chamber of Commerce estimated that at least 100-200 jobs had opened for African Americans in downtown Seattle. The Chamber also held the “Jobs Fair” on January 22nd and 23rd, which hosted over thirty employers offering jobs and information to thousands of applicants. 77 Near the end of his report, Valentine posed several questions in regards to the limited achievements of the DEEDS campaign and the widespread difficulties in planning and conducting a successful civil rights project. He asked the reader,

The Chamber of Commerce came forward as the main representative of private employers who would deal with us in DEEDS, but were we talking to the right people? If not, how can we get through to those who really make the decisions without going back to dealing with one employer at a time? How can we make a large, complex campaign like DEEDS more dramatically clear to the public? Was this project worth the financial expense involved? What can be done about the chronic problem that interest declines and manpower decreases for any project that continues over many months, through holiday seasons and periods of bad weather? Has DEEDS been too big a project for Seattle CORE, and if so how else can we produce significant change toward equal opportunity and an integrated society?78

These questions reflected the legitimate concerns of not only those involved in the DEEDS project, but for those fighting for civil rights issues throughout Seattle as well as the country. While Valentine’s report marked the closure of the DEEDS campaign for members of CORE, the national struggle to end employment discrimination continued well into the 1960s and beyond.

DEEDS was a remarkable and extensive campaign that demonstrated the devotion of the members of CORE as well as its local supporters. All the time and effort put into the project was voluntary, and not even the elected leaders received payment; therefore, individuals gave endless hours of their free time in order to make Seattle a more tolerant place. The full impact of DEEDS can never truly be measured, as the hiring of an increased number of African Americans could have been a result of the recently passed Civil Rights Act as opposed to the demonstrations put on by CORE. However, setting aside the debate regarding the reasons why employers began to give jobs to more blacks in the mid 1960s, the Seattle CORE chapter carried out countless campaigns during the civil rights era and contributed greatly to the advancement of African Americans in all sectors of the community. CORE stated in November of 1964, “if Negroes in America continue to gain jobs in the future at the same rate that they secured them from 1950 to 1960 it will take over 700 years for Negroes to secure 10 percent of all jobs in all categories in this country.”79 Fortunately, CORE’s prediction did not come true due to the heroic efforts of blacks and whites alike who were able to show that fervent passion and dedication towards a common goal can generate a significant change in society. May people one day in the future look at CORE’s DEEDS campaign and be inspired to bring about a change of their own in order to produce a more compassionate and tolerant world.

Copyright © 2007 Rachel Smith

HSTAA 498 Fall 2007

1 Leaflet, “An Appeal to Black and White Alike,” Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Ephemera.”

2 August Meier and Elliot Rudwick, CORE: a study in the civil rights movement, 1942-1968 (New York, Oxford University Press, 1973), 5-6.

3 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 8

4 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 9-10

5 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 10

6 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 23

7 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 144.

8 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 183.

9 Oral Interview with Joan Singler, Bettylou Valentine, Jean Adams. October 6, 2006, Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. < CORE.htm>. December 2, 2007.

10 Oral Interview with Joan Singler, Bettylou Valentine, Jean Adam

11 Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994) 4.

12 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 227.

13 Oral Interview with Joan Singler, Bettylou Valentine, Jean Adams.

14 Newspaper clipping,“Hundley to Direct Teen-Ager Research” Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Clippings.”

15 Mary T. Henry, “Hundley, Walter R. (1929-2002)”, The Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, http://www.historylink.org/essays/output.cfm?file_id=3173. December 8, 2007.

16 Oral Interview with Joan Singler, Bettylou Valentine, Jean Adams.

17 Charles A. Valentine, Deeds, background and basis; a report on research leading to the drive for equal employment in downtown Seattle (Seattle, Congress of Racial Equality, 1964), 1.

18 _“_Civil Rights Act of 1964,” < http://usinfo.state.gov/usa/infousa/laws/majorlaw/civilr19.htm>. November 18, 2007.

19 Valentine, Deeds, 3.

20 Membership Meeting Minutes, June 9, 1964, Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Minutes 1963-66”.

21 Valentine, Deeds, 8.

22 Valentine, Deeds, 7.

23 Valentine, Deeds, 10-11.

24 Valentine, Deeds, 11.

25 Valentine, Deeds, 11-12.

26 Valentine, Deeds, 12-13.

27 Valentine, Deeds, 16.

28 Valentine, Deeds, 18.

29 Valentine, Deeds, 21.

30 Valentine, Deeds, 22.

31 Valentine, Deeds, 23.

32 Valentine, Deeds, 24.

33 Valentine, Deeds, 25.

34 Valentine, Deeds, 24-30.

35 Valentine, Deeds, 34.

36 Valentine, Deeds, 35.

37 Valentine, Deeds, 39.

38 Valentine, Deeds, 40.

39 Valentine, Deeds, 45.

40 Valentine, Deeds, 45-46.

41 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 371.

42 Valentine, Deeds, 46.

43 Valentine, Deeds, 46-47.

44 Letter from Seattle CORE, August 5, 1964, Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Outgoing”

45 “Fact Sheet on National and Local CORE” (August 1964), Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Ephemera”.

46 “Fact Sheet on National and Local CORE” (August 1964).

47 Letter from Seattle CORE, August 26, 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Outgoing”

48 CORElator, September 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter CORElator”.

49 Letter from Seattle CORE, September 14, 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Outgoing”

50 CORElator, October 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter CORElator”

51 CORElator, September 1964.

52 Kathy M. Newman, _“From Sit-ins to ‘Shirt-ins’: Why Consumer Politics Matter More than Ever,” American Quarterly_, December 8, 2004), 213-221.

53 Meier and Rudwick, CORE, 60.

54 CORElator, October 1964.

55 Membership Meeting Minutes, October 13th, 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Minutes 1963-66”

56 CORElator, October 1964.

57 Leaflet, “CORE Rules and Procedures for Picketing,” Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Ephemera”

58 “Memo for Immediate Release from Seattle CORE,” October 23rd, 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Outgoing”

59 Leaflet, “An Appeal to Black and White Alike”

60 Poster, “CORE,” Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Ephemera”

61 Brochure, “DEEDS Project Goes Ahead,” Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Ephemera”

62 “Civil Rights Groups Indorse CORE Jobs Drive, but Not Boycott,”Seattle Times, October 25th, 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Clippings”

63 “Civil Rights Groups Indorse CORE Jobs Drive, but Not Boycott,”Seattle Times, Oct. 25, 1964

64 CORElator, November 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter CORElator”

65 Pledge cards, Seattle CORE. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #7, Folder “DEEDS Pledge Cards.”

66 CORElator, December 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter CORElator.”

67 Pledge cards, Seattle CORE. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #7, Folder “DEEDS Pledge Cards.”

68 CORElator, December 1964.

69 Valentine, Deeds, 47.

70 Membership Meeting Minutes, December 9th, 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Minutes 1963-66”

71 Letter from Seattle CORE, December 29th, 1964. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Outgoing”

72 CORElator, January 1965. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter CORElator”.

73 Newspaper clipping, “CORE, Business Disagree on Job Numbers,” Seattle Times, January 12th, 1965. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #6, Folder “Employment DEEDS Clippings”

74 Membership Meeting Minutes, January 12th, 1965. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Minutes 1963-66”

75 CORElator, February 1965. Seattle CORE Papers, UW Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter CORElator”

76 CORElator, February 1965.

77 CORElator, February 1965.

78 CORElator, February 1965.

79 CORElator, November 1964.