Civil rights activism in Washington’s Mexican-American community has its roots in two locales, the rural agricultural communities of the Yakima Valley and the Seattle urban area. This dualistic geography is reflected in the movement's activities, which by the late 1960s united the farm workers' struggle in the eastern portion of the state with campaigns targeting community and educational objectives in western Washington.

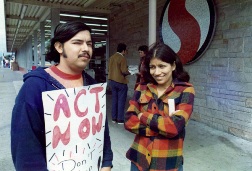

Much of this activism was generated by Chicano youth, and in particular students at the University of Washington and other campuses throughout the state. Students formed local chapters of the United Mexican American Students, the Brown Berets, and Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlan, among other organizations, and spearheaded initiatives both on and off-campus like the United Farm Workers Cooperative and the UFW grape boycott, El Centro de La Raza, SEAMAR and Consejo community health centers, and the Chicano Studies program at the UW.

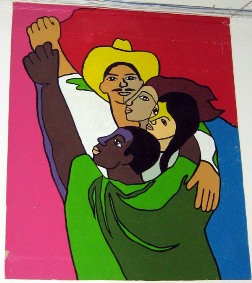

The Chicano movement was a cultural as well as a political movement, helping to construct new, transnational cultural identities and fueling a renaissance in politically charged visual, literary, and performance art. Active through the 1970s, the movement fragmented and lost momentum in the 1980s but has reemerged in recent years as a new generation of Chicano activists, building on the legacy of their predecessors, have mobilized around the issues of affirmative action, globalization, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and, most recently, immigrant rights.

The Chicano Youth Movement comes to the Northwest

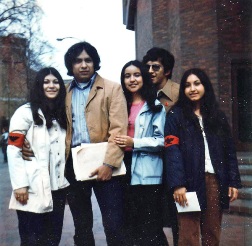

Though there is much debate over when the Chicano Movement as a whole began in the state of Washington, there is general agreement on the initiation of the student movement. In the late 1960s, Mexican-American youth, inspired by the farm workers’ strike in California, the African American freedom struggle, and the youth revolts of the time, began using the label ‘Chicano’ to denote their cultural heritage and assert their youthful energy and militancy. In appropriating a word that previously had a negative connotation, Mexican-American youth turned ‘Chicano’ into a politically charged term used for self-identification. Though there was activism at the individual level at Yakima Valley College and the University of Washington, the establishment of a movement organization did not take place until the fall of 1968, when the first large group of Chicano students arrived at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The new Chicano presence at the UW owed a great deal to the Black Student Union's (BSU) militant efforts to promote campus diversity. On May 20th 1968, BSU members occupied the offices of University of Washington President Charles Odegaard.1 The group organized a four hour sit-in where they voiced their demands for making the University more relevant to people of color by improving the recruitment of minority students, doubling black enrollment, increasing funding for minority student programming, and creating black studies courses. The BSU would lay the foundation for the recruitment of students from throughout the state, including Mexican-Americans. According to Jeremy Simer, "this connection between the BSU and Chicano students would later be strengthened by collaborative efforts on campus.”2 Of the thirty-five students that were recruited in 1968, most were from the Yakima Valley, the area that had the largest concentration of Latinos in Washington State.

At this time, the Yakima Valley had already seen the emergence of Chicano activism. Inspired by the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee’s (UFWOC) grape boycott, two students from Yakima Valley College, Guadalupe Gamboa and Tomas Villanueva, traveled down to Delano, California in 1967 and met with UFWOC leader Cesar Chavez. Upon returning, Gamboa and Villanueva co-founded the United Farm Worker’s Co-operative (UFWC) in Toppenish, Washington.3

The UFWC is credited as being the first activist Chicano organization in the state of Washington. Founded amid several War on Poverty efforts in the Valley, Tomas Villanueva recalled that the UFWC was "completely non-governmental." "I convinced people to give $5 into their shares and I got very successful. I got enough that would build a little store. It was very small to start with and we started running a sort of service defending people when growers did not pay their wages or when people got injured. We got people to get food stamps and those things. Then we found a bigger building for the co-op.”4

In the summer of 1968, the UFWC solicited the assistance of the Washington American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in a project that provided legal aid to people of farm working background. The report that emerged from the project underlined the conditions present in the Valley that forced Chicanos into a state of political and economic subjugation. As a result of various lawsuits filed through the ACLU, Yakima County was forced to take measures to ensure that Chicanos were afforded voting rights and bilingual ballots, as well as other considerations given to all people under the law.5 Though the UFWC organized workers during the wildcat strikes in the hop fields of Yakima County in 1970, the organization would not receive official recognition until the mid 1980s when it became the United Farm Workers of Washington State.

In addition to the UFW Co-op, there were other forms of activism in the Yakima Valley. The Cursillo Movement was organized through the Catholic Church. Though politically moderate, its purpose was to engage people in social action and encourage participation in church life. Another group formed in 1967, the Mexican American Federation (MAF), pointed toward a new direction in Mexican-American community organizing. In previous decades, most associations were social and cultural in nature. MAF was one of the first groups to advocate for community development and political empowerment in the Yakima Valley.

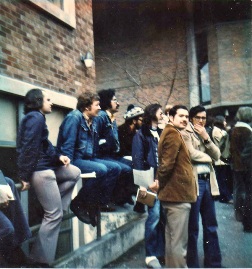

The fall of 1968 was characterized by social upheaval throughout the nation and the world. Universities at this time were hubs for political activity and discourse. Chicano students at the UW, few as they were, were inspired by this activity. They already possessed an understanding of the plight of farm workers as well as of the repressive, race-prejudiced system of power. Soon after setting foot on the UW Campus, the thirty-five Chicano students, led by Jose Correa, Antonio Salazar, Eron Maltos, Jesus Lemos, Erasmo Gamboa, and Eloy Apodaca, among many others, formed the first chapter of the United Mexican American Students (UMAS) in the Northwest. Modeled after the group that was founded at the University of Southern California in 1967, UW UMAS worked to establish a Mexican-American Studies class through the College of Arts & Sciences.

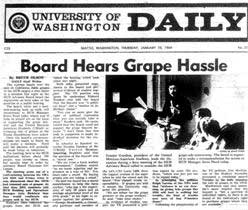

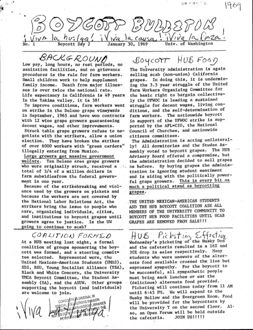

UMAS also engaged in a campaign to halt the sale of non-union table grapes at the University of Washington. Working alongside other activist organizations such as the BSU, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and members of the Associated Students of the University of Washington Board of Control and the Young Socialist Alliance, the group first petitioned the dormitories to stop selling grapes in their eating facilities, and quickly secured an agreement. But efforts to persuade the Husky Union Building (HUB) to cooperate proved more difficult.6 Nevertheless, on February 17, 1969 the UW Grape Boycott Committee was victorious as the HUB officially halted the sale of grapes.7 The victory made the University of Washington the first campus in the United States to remove grapes entirely from its eating facilities. Even more notable was the organization’s skill at building coalitions among other undergraduate groups, as evidenced by the diverse array of student groups on the boycott committee.8 At the national level, the grape boycott organized by the UFWOC achieved success in 1970 when the union won a contract.

In addition to the boycott, UMAS also called a conference in Toppenish to generate support for the creation of Chicano youth groups at the high school and college levels. With the assistance of UW faculty, UMAS created ‘La Escuelita’9 in Granger in 1969, which in turn led to the creation of the calmecac project (school in Nahuatl), a program that taught history and culture to Chicano youth in Eastern Washington.

The student movement was also spreading to other campuses. Following the lead of UW UMAS, Chicano students organized at Yakima Valley College to form a chapter of the Mexican American Student Association (MASA) in 1969. MASA, like UMAS, had its roots in southern California, originating out of East Los Angeles College. Later in 1969, Chicano students who had made their way to Washington State University in 1967 via the High School Equivalency Program organized another MASA chapter in Pullman.

1969 was a watershed year in activism at the national level as well. The Chicano Youth Liberation Conference, hosted by Corky Gonzalez’s Crusade for Justice in Denver, Colorado, laid the framework for a youth-initiated Chicano Power Movement. The conference produced one of the key documents of the period, “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan,” which rejected the earlier stance of most Mexican-American organizations and instead advocated a separate, third political space, away from both the political mainstream and the white-dominated student Left, which initially marginalized people of color. The conference also urged cultural regeneration, the negation of assimilation into the dominant society, and Chicano self-determination. This emphasis on cultural nationalism would persist well into the late seventies before the concept of activism ‘sin fronteras’ (without borders) and Marxist critiques of empire transformed the Chicano Left and laid the foundation for the Zapatista National Liberation Army’s (EZLN) revolution against neo-liberal economic doctrine in Chiapas, Mexico on New Year’s Day 1994.10

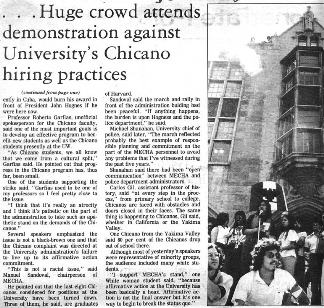

The Chicano Movement focused considerable attention on educational issues, especially access to higher education. Conscription and the Viet Nam war raised the stakes for young Chicanos. Because of the availability of student deferments, access to higher education often times had literal life or death implications for Chicano youth who were at risk of being conscripted. As a result of many of the concerns associated with higher education, the Chicano Council on Higher Education, formed after the Massive East Los Angeles High School Walkouts of 1968, organized a conference at the University of California at Santa Barbara11.

The resulting document, "El Plan de Santa Barbara," laid the framework for a master plan related to curriculum, services, and access to higher education. It became a blueprint for the implementation of Chicano Studies and EOP programs throughout the West Coast, including the University of Washington, and also outlined the role of the University in the community and in issues of social justice. The conference also transformed the way Chicano students organized themselves. The delegates decided to merge the many activist organizations – UMAS, MASA, MASO, MASC, MAYO, among others – under the umbrella of El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (The Chicano Student Movement of Aztlan). MEChA soon became the primary vehicle for student activism on campuses throughout the United States.

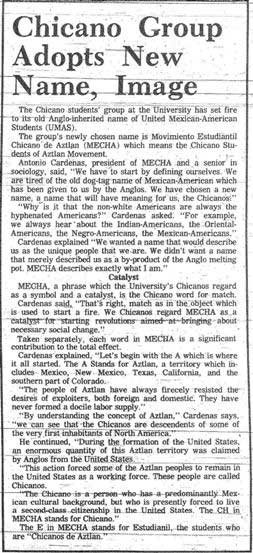

In the fall of 1969, UW UMAS officially adopted the name MEChA. This reflected a shift in consciousness as well as a generational change as members rejected the term ‘Mexican-American’ in favor of the label ‘Chicano.’ Over the next two years, Yakima Valley College and Washington State University would follow suit. Throughout the 1970s, numerous MEChA chapters emerged in Washington State, including groups in the Columbia Basin, at Seattle Central Community College, Central Washington University, A.C. Davis High School in Yakima, and various other communities. In April of 1972, students organized the first statewide MEChA Conference at Yakima Valley College. The conference resulted in the creation of a statewide board authorized to facilitate communication between all MEChA chapters in Washington about activities at the state level. Chicanos near the Spokane area waited until 1977 to organize at Eastern Washington University, and it wasn’t until 1978 that the organization affiliated with MEChA.12

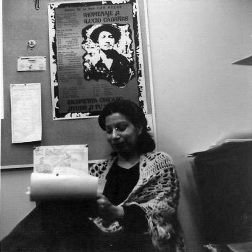

According to Jesus Rodriguez, in the few years after the organization was established, “MEChA became more diversified and developed subgroups to deal with specific problems in health, women’s issues, community concerns, graduate students and so forth.”13 In effect, MEChA became an umbrella organization that housed such groups as Las Chicanas, the Brown Berets, the National Chicano Health Association, and the Chicano Graduate and Professional Student Association. In fact, many students were involved in multiple groups at one time, as there was participation across the several entities presided over by MEChA.

The Brown Berets

Throughout the period, activism on campuses was accompanied by activism in the community, and the Brown Berets emerged as a key organization linking students to communities and to young people who were not enrolled in college. Brown Beret chapters formed in both Yakima and Seattle and by 1970 had attracted over 200 members. Originally founded in California, the Brown Berets gave a new and tougher look to the movement in the late 1960s.

What would become the Brown Berets originated when six young Chicanos formed the core of the Young Citizens for Community Action (YCCA) in May of 1966 in Los Angeles. Far from radical, the group participated with the Community Service Organization (CSO), where they met with political leaders who, according to Ernesto Chavez, "schooled them in the ways of practical politics and community organizing and who also introduced them to the now famed Cesar Chavez.”14 With financial help from Father John B. Luce, rector of the Episcopal Church of the Epiphany in Lincoln Heights, the group opened ‘La Piranya,’ a coffeehouse that doubled as an office and meeting place where prominent civil rights speakers spoke to increasing numbers of Chicano youth.15

This activity attracted police who began harassing young people at the coffeehouse. YCCA responded by organizing protest demonstrations at nearby sheriff stations. Young leaders such as David Sanchez viewed harassment at the coffeehouse as symptomatic of the larger problem of police abuse in the Chicano community and advocated a more militant stance. In January of 1968, the YCCA adopted a new image and uniform, becoming the Brown Berets. As Chavez writes, “Law enforcement abuses had transformed them from moderate reformers into visually distinctive and combative crusaders on behalf of justice for Chicanos.”16 By 1969, La Causa, the Berets newspaper, reported that the Brown Berets had approximately twenty-eight chapters throughout the West Coast and Midwest. Two of these chapters were in the state of Washington.17

The UW Brown Berets most likely originated in Granger, Washington. The group was then transplanted to Seattle as students from the Yakima Valley were recruited to the University of Washington in the late sixties and early seventies. According to former student activist Pedro Acevez, it was Carlos Treviño, Trevino's brother, and Luis Gamboa who first "came up with this Brown Beret thing.”18

The organization was comprised mostly of motivated, militant university students and youth from Seattle’s Chicano community. Rogelio Riojas recalls that the Seattle chapter was a “group of men and women that wanted to work at the community level.”19 Much like the groups in Southern California, the UW Brown Berets donned their distinctive headgear and military fatigues as a symbolic statement that they were willing to fight for their communities, bringing attention to the war at home in the barrios against racial discrimination, poverty, and police brutality. The Brown Berets uncompromising stance on these issues attracted Chicano youth to the organization. Referring to instances when the Brown Berets acted in defense of students being harassed or intimidated by others, Pedro Acevez recalls, “I perceived them as a positive. [Sometimes] the muscle of the brown berets came in handy.”20 On the other hand, older members of the community were more reluctant to support the confrontational tactics of the Brown Berets, reflecting the generational differences in the Chicano community.

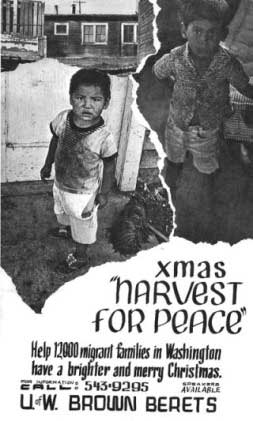

The Brown Berets initiated or participated in a number of programs targeted at the specific needs of the local community. According to Jesus Lemos, “in the winter of 1970, the Seattle chapter organized a ‘Food for Peace’ drive to gather food, clothing and money in order to make and distribute Christmas baskets to the Chicanos in the Yakima Valley who were in the most need.”21 The UW chapter also engaged in other activities such as the creation of a legal defense fund for Chicano activists and active involvement in support of UFW activities such as the grape boycott. As Riojas recalls, “we were raising money for UFW, going to Olympia, and helping [in the] community.”22 The Brown Berets financed most activity through collection drives and requesting funds from sympathetic staff and faculty at the University.23

The chapter in the Yakima Valley also emerged as a strong force agitating for an end to Chicano oppression in Central Washington. According to Lemos, “In the early part of 1970 they organized a five-mile march to the welfare office in Yakima to protest the abuse of the Chicanos who were often ridiculed and treated with great disrespect and insensitivity by the welfare authorities.”24 Along with this activity, the Yakima Valley Brown Berets also played a supportive role in “La Escuelita” in Granger and were involved with other groups in "El Año del Mexicano,” which sought an increased political role for Chicanos in the Yakima Valley. However, the Yakima Valley chapter had trouble maintaining consistent membership. It became inactive a few weeks after the march on the welfare office in Yakima.25

As time progressed, the Seattle Brown Berets served more in the capacity of a subgroup under UW MEChA.26 For the remainder of the group’s “official” existence, it was the wing of the Chicano student movement most closely rooted in the community.27 The Brown Berets also tried to launch the La Raza Unida Party in the state of Washington.28 The party was an effort to unite Chicanos on both sides of the Cascade Mountains. Despite this effort, La Raza Unida Party in Washington never grew past its embryonic stage and folded before really taking off. In Seattle, the Brown Berets acted as the ‘muscle’ during many of the demonstrations that MEChA undertook on the UW campus and, much like the Black Panthers, raised a red flag in conservative sectors of the white community. Along with another subgroup, Las Chicanas, the Brown Berets were also an integral part of the contingent that occupied the old Beacon Hill elementary school in October of 1972 and demanded the creation of El Centro de La Raza.

El Centro de La Raza

The site of what is now El Centro de La Raza lay abandoned by the Seattle school district for some time before the occupation of the building on October 12, 1972. At the time, many of the services provided for Seattle’s Chicano/Latino community were scattered throughout the city. This decentralization made it difficult for many who sought after services to obtain them. The economic crunch of the early seventies saw many programs sent to the chopping block, as was the case with one English as a Second Language program in the south end of Seattle that had a social justice component. The takeover of the Beacon Hill school was a response to the cancellation of the ESL program for the Chicano community at South Seattle Community College. Students and community members affected by the sudden closing of the program were instrumental in planning the takeover. Juan Jose Bocanegra remembers, “we brought in Chicanos from the University of Washington. Everyone just popped out of the cars and started walking toward the door. The press started showing at around 9:00.”29

The effort was orchestrated with three main contingents that allowed for occupation while keeping lines of communication open to the community and the city. “We would have a team that would bring food and support, another group dealing with the cops, and another to deal with the city, recalls Bocanegra.”30 The takeover lasted into 1973 as negotiations took place with the Seattle City Council and the Seattle school district, all while demonstrators occupied the old Beacon Hill school and made due without water or electricity throughout the duration of the standoff. Ricardo Martinez, one of the UW students involved in the takeover, recalls his experience: “I remember the first few nights we were there. It was cold! It was really cold, there was no heat, there was no power. … The eventual takeover lasted months. … We would come and go, and spell each other.”31

The struggle for El Centro proved difficult. Although the campaign was spearheaded by the Latino community, alliances across racial and ethnic lines were instrumental in keeping up the fight with the Seattle City Council. At one point, activists occupied the City Council chambers in an effort to force city leaders to turn over the building. After much debate, the city of Seattle finally conceded and allowed the use of the property for the creation of El Centro de La Raza in 1973. As former Brown Beret Rogelio Riojas put it, “someone opened the door and we went in and never left.”32

At a time when there was no distinct Chicano “barrio” in Seattle, the creation of a center that housed many of the services that Chicanos lacked was a necessity. El Centro became not only a community center, but also a civil rights organization that developed progressive coalitions with activist groups rooted in other ethnic communities, especially Native Americans. According to Ricardo Martinez, “The genesis" of the Beacon Hill takeover "was that the Native Americans had taken over the Daybreak center” at Fort Lawton.33 These alliances would continue throughout the 1970s and to the present day.

Much of the social justice work done by El Centro is outlined in its mission statement, which includes "ensuring access to services and advocating on behalf of people regardless of race, color, creed, national origin, gender, level of income, age, ability and sexual orientation.”34In later years, the organization was also involved in issues of labor, including farm worker organizing in the state of Washington and supporting much of the work done in California by Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and the United Farm Workers Union.

El Centro also worked in solidarity with international struggles, most notably in Central and South America. Roberto Maestas recalls an event El Centro hosted on behalf of earthquake victims in Managua that attracted numerous Nicaraguan exiles living in Seattle, many of whom had escaped the U.S.-backed Somoza family dictatorship.35 This solidarity with the Central American community continued throughout the 1970s as El Centro helped maintain communication with the Sandinista government, which ultimately overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in 1979. In 1983 El Centro de La Raza sent a delegation and a crew from Seattle's KING-TV on a fact-finding mission to Nicaragua. The Sandinista government hosted the delegation for a week as the group talked to people in the towns affected by attacks by counterrevolutionary groups.

The creation of El Centro de La Raza was the result of a community coming together to forge space for furthering the cause social justice for Latinos and Chicanos in Seattle.36 El Centro represented one of the first major attempts in the Seattle area to create community institutions to better conditions for the people. When recalling the creation of the center, Ricardo Martinez remembers “how fun it was being together with a bunch of people doing something that [we] thought was the right thing to do for all the right reasons. [We] were hoping the end results would justify what [we] were doing.”37

Building Community Institutions

The acute isolation for many Chicanos from other cultural urban centers in the Southwest made the interaction between students at the UW and the Chicano community of Seattle even more noteworthy. In fact, the Chicano student movement at the University of Washington provided the impetus for new community institutions and a new era in the development of the arts and literature in Seattle and throughout the region. This energy would emerge through the efforts of staff and faculty, as well as UW MEChA, the oldest student-initiated Chicano activist organization in the Northwest.

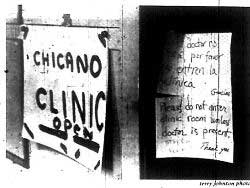

At the community level, former student activists sparked the creation of SEAMAR38 and Consejo39 community health centers in 1978. The two centers initially served the Western Washington Latino community, expanding over time to other low-income communities as well. SEMAR emulated the farm worker’s clinic in the Yakima Valley by offering holistic medical services, while Consejo focused primarily on mental health and chemical dependency. These institutions remain vital in providing access to health care for the Chicano and Latino immigrant communities.

In Seattle, the late 1970s witnessed the establishment of a chapter of the Center for Autonomous Social Action (CASA).40 CASA, which was originally founded in Los Angeles in 1968, was a group that blended cultural nationalism with Marxist-Leninist thought, becoming the first Chicano Marxist organization organized by poor and working-class Chicanos. The organization started as a mutual aid association that then organized around ridding the local barrios of illegal drugs. As the group developed, it began organizing workers regardless of legal status and forged coalitions with Mexican socialists and the Puerto Rican Socialist Party. This turn toward a more internationalist ideology was a reflection of the changing demographics of the 1970s and was a response to a renewed anti-immigrant backlash.

At the national level, the harsh anti-immigrant policies brought forth by the Carter administration, as well as the patrolling of the southern border by the Ku Klux Klan, prompted many Chicano activists to take action by organizing opposition to the nativist sentiment echoed by the right wing in the late 1970s. In the Yakima Valley the contributions of community activists resulted in the creation of Radio KDNA in 1979.41 KDNA was the first radio station to dedicate its entire programming to the Spanish-speaking population of Eastern Washington. To this day, the station is nationally recognized for progressive programming that serves to educate people on various issues concerning health, labor, and culture. Much like the organizations that were created in Seattle during the late 1970s, Radio KDNA has been instrumental in advocating for the rights of workers regardless of legal status.

Continue Part 2: Chicano Cultural Awakening

Copyright(c) Oscar Rosales Castañeda 2006

McNair Scholarship project 2005-06

1 Walt Crowley, Rites of Passage: A Memoir of the Sixties in Seattle (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995), 255

2 Jeremy Simer, “La Raza Comes To Campus: the new Chicano contingent and the grape boycott at the University of Washington, 1968-69.” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 2004-2006 <la_raza2.htm>

3 Jesus Lemos, “A History of the Chicano Political Involvement and the Organizational Efforts of the United Farm Workers Union in the Yakima Valley, Washington,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Washington, 1974), 54

4 Tomas Villanueva Interview, 11 April 2003, 7 June 2004 by Anne O’Neill and Sharon Walker

5 Charles E. Ehlert, “Report of the Yakima Valley Project.” Seattle, WA: American Civil Liberties Union, 1969.

6 John Greely, “Hub Board Recommends Stoppage of Grape Sales,” University of Washington Daily (6 February 1969): 1.

7 Jeremy Simer, “La Raza Comes To Campus” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 2004-2006 <la_raza2.htm>

8 Simer, “La Raza” Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 2004-2006 <la_raza2.htm>

9Lemos. “History of the Chicano Political Involvement,” 56-58.

10 For more information on the EZLN, consult http://www.ezln.org

11 On March 3, 1968, more than 1000 students aided by members of U.M.A.S and the Brown Berets, peacefully walked out of Abraham Lincoln High School in East Los Angeles, with Lincoln High Teacher Sal Castro joining the group of students in protest of school conditions. The student strike, known as the L.A. Blowouts, would result in over 10,000 high school students walking out by the end of the week. To this day, the event remains one of the largest student strikes at the high school level in the history of the United States.

12 Gilberto Garcia, “Organizational Activity and Political Empowerment: Chicano Politics in the Pacific Northwest,” in The Chicano Experience in the Northwest, (Dubuque, IA.: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co., 1995), 75-80

13Jesus Rodriguez, MEChA Newsletter University of Washington, 1981, p. 1-2, Jesus Rodriguez Papers, MEChA de UW Archives.

14Ernesto, Chavez. “Mi Raza Primero!”Nationalism, Identity and Insurgency in the Chicano Movement” Berkeley, CA: UC Press, 2002, 44.

15 Among those who would come speak to the youth were Reies Lopez Tijerina of New Mexico’s Land Grant Movement, as well as leaders such as Hubert “Rap” Brown and Stokely Carmichael of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, among others. Chavez, Mi Raza Primero! 45.

16 Chavez, Mi Raza Primero, 45.

17 According to Ernesto Chavez’ notes, in May 1969 the Beret newspaper La Causa reported that the organization had twenty-eight chapters in cities including San Antonio, Texas; Eugene, Oregon; Denver, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; Seattle, Washington; and Albuquerque, New Mexico; along with many cities in California. (see La Causa, May 23, 1969); Chavez, 132.

18 Pedro Acevez Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 27 January 2006 by Edgar Flores and Oscar Rosales.

19 Riojas Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 19 January 2006

20 Pedro Acevez Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 27 January 2006

21 Lemos, 57.

22Riojas Interview, 19 January 2006

23Riojas , 19 January 2006

24 Lemos, 58.

25 The Brown Beret chapter in the Yakima Valley became inactive in 1970 after a key leader lost credibility in the Chicano community. Despite severing ties to the former leader, the group was unable to regain the community’s trust because of past ties to the disgraced former co-founder. Lemos, 61.

26 Jesus Rodriguez, MEChA Newsletter University of Washington, 1981, p. 1-2, Jesus Rodriguez Papers, MEChA de UW Archives.

27 It was later revealed that the Brown Berets were infiltrated and destroyed from within by the COINTELPRO program.

28Jesus Rodriguez Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 3 March 2006 by Roberto Alvizo and Cristal Barragan.

29 Juan Jose Bocanegra Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 2 February 2006 by Chris Paredes, Cristal Barragan and Trevor Griffey

30 Bocanegra, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 2 February 2006

31 Ricardo Martinez Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 8 February 2006 by Oscar Rosales and Edgar Flores

32 Riojas, 19 January 2006

33Martinez Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. 8 February 2006

34 For additional information see El Centro de La Raza’s website, <http://www.elcentrodelaraza.org/>

35 Roberto Maestas Interview, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project, 22 February 2005 by Trevor Griffey

36 <http://www.elcentrodelaraza.org/>

37 Martinez, 8 February 2006

38 SEAMAR Community Health Centers, <http://www.seamar.org/>

39 Consejo Counseling and Referral Services, <http://www.consejo-wa.org/Anniversary.htm>

40 In 1968 Soledad Alatorre and Bert Corona set up the Center for Autonomous Social Action-General Brotherhood of Workers (CASA-HGT). The group is one of the first to spearhead a move toward organizing both legal and undocumented workers under the banner of 'sin fronteras' or 'without borders.' In 1973 CASA's ideology takes a turn farther toward the left, making it the first Marxist-Leninist Organization based inside the Chicano Community. The student element comprised of a group of students from Los Angeles and Orange County form El Comite Estudiantil del Pueblo. The group, made up primarily of Chicano Marxists, sought "anti-imperialist solidarity with national and international student struggles, university reform, self-determination against the 'imperial system,' and student-worker unity." The group would later merge with CASA. The organization would reach all throughout the west coast, with chapters as far away as Chicago, Illinois, and as far north as Seattle, Washington(Also see, Rodolfo Acuña, Occupied America: A History of Chicanos. Fifth ED. New York, N.Y.: Pearson Longman, 2004, p. 353)

41 Radio KDNA online, <http://www.radiokdna.org/>N.Y.: Verso, 1989. p. 99-126).