“The Part She Played”, by Susie Cayton, is the story of Mrs. Crosswaite, a woman who asserts her power as the moral backbone of the family. In this short story, the end justifies the means when Mrs. Crosswaite falsely presents herself as helplessly drunk in an effort to subtly convince her husband of his duty to focus attention towards the home for family stability.

Finally, some might say womanlike, Mrs. Crosswaite owned to the part she played, but she said: ‘I thought you ought to spend your time in your own home and you now have for your wife a very happy woman.’1

As an educated African American woman in early twentieth century America, Susie Cayton exercised the parts she played to advocate for the social mobility of her race. The title of her story spoke to the complicated roles Susie played in her own life as an African American wife, mother, and social activist in twentieth century America. Seattle was her home from 1896 to 1940, and in that time she raised a legendary family, exercised her skills as a newsworthy and talented writer, and was dedicated to the social advancement of African Americans. The literary works left behind by Susie Cayton provide a window into her personal life and help clarify her commitment to the social uplift of the Northwest community.

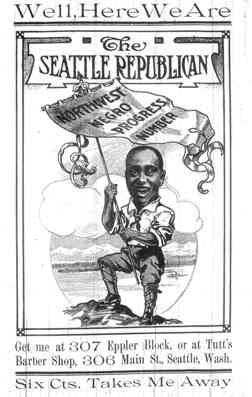

Her husband, Horace Cayton, publisher of the Seattle Republican and later Cayton’s Weekly, is well known to historians, as are her two sons, Horace Cayton Jr., the eminent sociologist, and Revels Cayton, the labor activist. Susie Cayton’s biography is still being pieced together. Important contributions have been made by Richard Hobbs, whose book The Cayton Legacy: An African American Family, is based on extensive interviews with Cayton descendents. Historian, Quintard Taylor, gives significant attention to the Cayton family in The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era and wrote several essays recognizing Mrs. Cayton’s social activist efforts in the Northwest. Finally, local historian Ed Diaz beautifully compiled Susie Cayton’s literary efforts in Stories by Cayton. This essay builds on those sources while also examining stories that Susie Cayton wrote for the Seattle Republican.

The Urban Climate in early Twentieth Century Seattle

As owners of the Seattle Republican, the newspaper that Horace Cayton founded in 1896, the Cayton family was one of Seattle’s most prominent middle class African American families, but the limited opportunities for African Americans in the area continued to make their position within the social milieu difficult. When Susie arrived Mississippi in 1896, the black community made up less than one percent of the total population of Seattle. In 1900, the black community numbered 406 out of nearly 81,000 total residents in Seattle.2 Blacks were not the only significant racial minority, as was the case in the South. Seattle featured a complicated demography where Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Native American, and African American communities all existed in a framework of white supremacy. Caught in the employment restrictions exercised by Seattle’s largely white dominated labor unions, unskilled blacks generally found themselves limited to jobs as janitors, porters, and domestic workers.3 Effectively locked out of lucrative professions and small in number, Seattle’s pre-World War II black community lived in a space that symbolized the lesser evil for those escaping the racial tensions of the Northeast and South.

Despite the overt discriminatory practices in employment and housing opportunity, Washington Territory was uniquely progressive in comparison to the rest of the nation at the turn of the nineteenth century. Black males were able to vote. In contrast to segregationist laws, race riots, and the violence of white supremacy prevalent in the South, Washington had no discriminatory laws on the books at the turn of the century. In 1890, the Washington State legislature passed the Public Accommodation Act which protected civil and legal rights for all Washingtonians and banned racial discriminatory practices.4 Yet, in 1895, the state dropped the penalties associated with the act, thus nullifying any potential enforcement of the law.5

Daughter of the First African American Senator

Susie Cayton’s prominence within the black community came partly from her being the daughter of Hiram Revels, the first African American elected to the U.S Senate. Born Susie Sumner Revels to parents Hiram and Pheobe Bass Revels in 1870, she was the third generation of free blacks from her family, spanning before the Civil War. Susie was given her middle name in honor of Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts Senator who had let the fight in Congress to abolish slavery. Sumner was also one of the architects of the Reconstruction measures that had given former slaves the chance to vote and hold political positions after the Civil War. Susie’s father, Hiram Revels, had won election as Senator from Mississippi in 1870, taking the seat that had once been held by the confederate leader Jefferson Davis.6 Her birth came the same year her father was sworn into Senate. Susie spent the beginning years of her life in Washington D.C. until her father moved to Mississippi to lead Alcorn University.

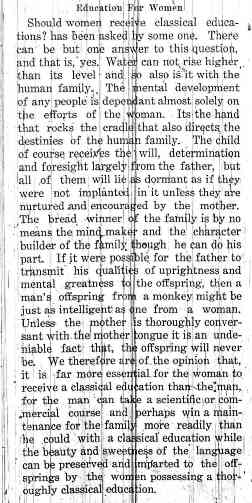

Raised in the shadow of her father’s political success, Susie’s upbringing was remarkable in comparison to the majority of blacks of her time. Young Susie pursued her interest in writing and by the age of sixteen she received a degree from Rust University in Holly Springs, Mississippi. She taught at the university for three years and later returned to the school as a student where she earned a degree in nurse training at the age of twenty-three.7 While in Mississippi near her parents, she came across the Seattle Republican, a Northwest newspaper sent to her father, Hiram Revels, by the editor, Horace Cayton. Horace had attended Alcorn University during the time Susie’s father led the school and developed a deep respect for the former Senator.8 In Seattle, he had been able to navigate his way into a position of power within the Washington State Republican Party. A position significant enough that he could successfully publish a partisan newspaper that impressed both Susie and her father. Susie responded to Horace’s journalistic success and submitted her own work to the Seattle Republican. Which was the beginning of the personal connection and long distance courtship between the two.

A Writer in Her Own Right

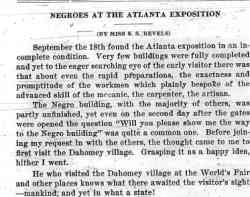

Susie Cayton not only played the part of a highly motivated woman within the African American community she sought to write the part that would contribute to the history of African American’s in the Pacific Northwest. In 1896, Horace Cayton premiered Susie Revels’ work to the Northwest audience in the January 4th edition of Seattle Republican. The edition of the paper featured a photo of Susie and an article she wrote entitled, “Negroes at the Atlanta Exposition.” In this article, Miss Susie Revels reported meeting with Chief John Tevi of the West African Dahomey tribe. Tevi had been accused of exploiting villagers he guided around the world to perform at events such as the World’s Fair.9 But Susie Revels was unimpressed by the accusations, and instead expressed great respect for the Africans Tevi traveled with and the message he offered. In her article Susie wrote:

And these were human beings to whom the world of letters was if it were not; human beings for whom the day of life in all its richest beauty had never dawned; human beings who were not conscious that the great age of progress was rolling onward and upward…Is there hidden in those minds a genius the uncovering of which would surprise the world and make it a more inhabitable “tenting ground?” Yea, came the answer; as surely as those bodies contain souls capable of the highest impulses and desires… –Susie Cayton 1896.10

Six months after the article was published, Susie moved to Seattle to marry Horace Cayton. The arrival of Susie to Seattle is described by Richard Hobbs in The Cayton Legacy: “When she arrived in Seattle, her betrothed—a proper Victorian gentleman—arranged separated lodgings until they could be married.”11 The two wed on July 12th, 1896, when Susie was 26. Susie and Horace’s joining was a complementary exchange of academic, social and political status combined with a fervor to assist in the advancement of the black race.

Tales of the exotic laced with irony, horror, humor, and deep sentimentality, were common themes found in Susie Cayton’s writing. In 1902, Seattle Republican published, “In the Land of Fire,” a short story by Mrs. Susie Cayton, wherein Barkri, a woman raised in a rural society in South America, matures to discover the customs of her land as intolerable. Children are raised to forget their familial ties, sickly children are thrown into pits of fire, and useless women are victims of cannibalism. When her husband dies at sea, and the tribe threatens to send her sickly baby to the fire pits, Barkri seeks refuge and raises her daughter in anonymity in the mountains to avoid the tragic result of tribal tradition. The baby survived but grew to forget the origins of her family.

…Barkri was becoming elderly and thereby one of the useless women of the island, and her daughter never by look or sign recognized her, who was ever near in time of sickness or trouble, never asked how or why the most choice fish and portions of seal fell to her lot.12

Later, Barkri is met by a detective who tells her she is a U.S. citizen, but Barkri refuses to leave the daughter who had already forgotten her. The night before the detective is to leave Barkri attends a tribal gathering.

…the subject of discussion was the slaying of several old women, and among those named was Barkri.[…] When Barkri’s name was called a tall woman of middle age arose and spoke for a portion of her body on which to feast. ‘Twas Barkri’s daughter.13

Needless to say, Barkri leaves to the U.S. with the detective but her heart still remained in the “Land of Fire”.

Barkri is an outcast in her community because she is able to recognize the inhumane acts carried out as custom in her land. Perhaps Susie tried to capture the beginnings of enlightened thinking among captive slaves, or her own juxtaposition within black society as an educated woman. The notion of severed familial ties alludes to the social destruction blacks experienced during slavery. “The Land of Fire” is a provocative tale which, like many of her stories, allowed Susie to relay larger societal issues through literary imagery.

Wife and Associate Editor of Seattle Republican

Susie’s privileged family heritage coupled with the success of the Seattle Republican made many blacks skeptical of the Cayton’s intentions. Mrs. Cayton stood apart from her female counterparts, white and black. Following emancipation and in the aftermath of reconstruction, most women of Susie’s time were caught up with the demands of individual and familial survival. Many blacks were reduced to the simple task of keeping food on the table during the early twentieth century. As an elite and educated third generation free black woman, Mrs. Cayton was self consciously different. Much like the integrity Seattle Republican wished to portray, many of the characters in Susie Cayton’s stories were ambiguous in racial affiliation. Stories such as, “The Part She Played”, “Last Rites”, and “My Meeting with the Presence”, focused on themes central to human experience. Susie also contributed to the success of Seattle Republican as associate editor by delivering newsworthy articles for the black and white community. A short article found in Seattle Republican entitled “Stop Your Paper” illustrates the complicated nature of the Cayton’s position as a middle class black family providing a newspaper for a multiracial Seattle audience:

A colored subscriber wants the paper stopped because “it has nothing in it.” A white subscriber orders his paper discontinued because “it has too much colored news in it.” So between the two, the financier has the devils own time to keep things going.14 – Seattle Republican, 1906.

Although the majority of Seattle Republican’s patrons were white, Horace and Susie struggled to meet the needs of both the black and white community. The complicated editorial strategy did not always sit well withvthe black community. Some in the community saw the Cayton’s as catering to white society.15

In 1970, University of Washington students interviewed Virginia Clark Gayton. The Gayton family has a prominent history in 20th century Seattle Susie Cayton was the godmother of Virginia Gayton’s husband, John Jacob Gayton.16 But in the interview, Virginia, who was only a child at the time of the Caytons’ greatest success, recalled the prominence of the Cayton family with a backhanded compliment that suggested their difference from the rest of the African American community: “They [the Caytons] had a beautiful home on Castle [Capital] Hill and had Japanese servants and what not. And so they didn’t have to do any housework.”17Gayton went on to suggest that the Caytons didn’t represent the average African American, and in turn, were inattentive to the practical needs of the black community. She added that “They had a good educational background and a history of disagreeing and, you know, fighting for what they…”18 It is with this statement that Gayton stops short without ending her sentence, but the impression is that the Caytons were perceived as neglecting black issues and focusing on their own success.

Virginia Clark Gayton also drew a distinction between middle class and laboring blacks in general arguing that, “In the South the educated Black people…they had the same [problem] copying white culture. They looked down on people who did laboring work.”19 While there is no evidence to suggest that Susie treated blue collar workers any differently, her indifference to menial labor didn’t go unnoticed by the black community. In her interview, Virginia Gayton went on to share that “of course after they lost the money [following the demise of the Seattle Republican], why they didn’t know exactly how to cope with that. I think that’s because Mrs. Cayton didn’t know to keep house and it was such a blow to Mr. Cayton.”20 Gayton’s comments seemed to express resentment about Mrs. Cayton’s heritage as she adds, “She had been raised to have maids.”21

In his biography of the Cayton family, Richard Hobbs provides a contrasting picture of Susie as someone who had servants but didn’t think herself above them. Recounting an argument described by Horace Jr. in The Long Old Road, Hobbs wrote that Horace Sr. tried to forbid Susie from talking to Nish, their Japanese servant, and Mr. Fontello, the garbage man, stating, they should be “kept in their place.” Mrs. Cayton is said to have defiantly retorted that the garbage man was “one of the most intelligent men she had ever met, and I will continue to talk with him for as long as I please.” Susie said she could learn Japanese from Mr. Nish, and that Mr. Fontello was a good conversationalist.22

Horace himself, rather than seeing his wife’s desire to write and be active in the community as a detriment, saw it as his greatest strength. In the July 23rd, 1909, edition of Seattle Republican, Susie Cayton’s husband praised his wife in the article, “Good Woman’s Helping Hand.” Horace described Mrs. Cayton as a woman “…who not only makes husbands men in the true sense of the word, but who makes the men and women of tomorrow.” At the time of this article, Susie and Horace Cayton had just celebrated their thirteenth anniversary. In 1909 The Seattle Republican was recognized by the Seattle Times for not missing an issue since its debut and in the following July 23rd article Horace attributes this achievement to Susie:

Not partially due, but we ourselves, sometimes think wholly due to the fact, for bless her heart, she has for all these years stood like a stone wall by our side and some times when the battle for existence was so severe that to live through it seemed more than human, she never waivered.23

As an Activist in the Black Community

Susie’s piece, “Black Baby Dolls,” speaks to the progressive nature of the issues she addressed in the black community. Ahead of popular opinion and academic scholarship on the issue, Susie warned of the psychological harm of having black children play with white baby dolls. She encouraged black parents to make their own dolls, and not to settle if retailers refused to stock black dolls.24 It was from the ground up that Susie saw change needed to be made and she recognized the message white dolls were sending to black children.

At a time when blacks were consumed with economic survival in the face of discrimination, children’s toys may have appeared a bit of a privileged topic. But in fact it was part of a broader social vision that Mrs. Cayton chose to address. The majority of women’s social work within the black community centered on activism through the church. Susie Cayton often acted outside these boundaries, and took it upon herself to exercise her ingenuity and social status to tackle particular problems.

In 1906, Mrs. Cayton organized a group of black women in the community to assist twin baby girls orphaned and sick with the rickets. King County Hospital sent the girls to a mental institution in Medical Lake, Washington. Through her organizing efforts, Susie not only rescued the girls and sponsored a foster family for them.25 In the same stride she founded the Dorcas Charity Club, which was recognized as one of the more active clubs in the Seattle area. Susie’s social circle focused on welfare issues and the progress of the black opportunity. The Dorcas Charity Club alleviated some of the harsher conditions facing African Americans. They provided toys for orphans and living expenses for widows in Seattle’s black community.26 The Dorcas Club sought to help the most destitute of the black community. Possibly Susie Cayton’s most well documented legacy, with exception to her literary works left behind, the Dorcas Charity Club focused on social welfare issues and individual advancement in the black community. In 1907, The Dorcas Club aligned with the founders of Seattle Children’s Hospital to establish a policy of prohibiting discrimination of race, religion, or ability to pay when it came to accepting and treating sick or malnourished children.27 This alliance was a great advancement to the social services extended to blacks at the time. There are also reports of the Dorcas Charity Club greeting black troops in Spokane during World War I.28

From Progressive Reformer to Communist Party Activist

In the early 1930s, in the midst of the Depression, with the Republican Party tied to failed economic policies and the Democratic Party still the party of southern segregationists, Susie Cayton split with her husband and joined with her son Revels in supporting the Communist Party.

While some might have been surprised by the shift, there were earlier indications that Susie was more attached to uplift than political boundaries. In her 1918 story, “My Meeting with the Presence,” Susie describes in first person the experience of spiritual awakening through the extension of empathy to mankind. The author goes through a series of accepting steps or prayers for saving her individual soul, then her family’s souls, the souls of the Negro race, and, finally, with her last prayer to save the souls of all mankind, she is “transformed”: “‘God save the world,’ vehemently I prayed”.29 She goes on to write:

Then intently I listened. Clearly I could distinguish the different sounds: the cries caused by poverty, discontent and greed; by malice, injustice and immorality and high above them all rose the piercing wails caused by the selfishness of mankind.30

Perhaps communism resonated with Susie Cayton’s values of social equality and community commitment. The Cayton matriarch had surely benefited from both witnessing her son Revels rise in political power through his involvement with communist factions of the West Coast maritime labor movement, and from the famous communist-affiliated visitors she received at her Seattle home.

…one day Susie answered a knock at the front door. A large, tall man nearly filled the doorway. ‘I’m Paul Robeson,’ he said. ‘I’m on concert tour here, and so many people have told me about you that I just wanted to come up and see you.’”31

The part she played as an activist in Seattle’s black community provoked legendary African Americans Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes to take up company in the Cayton home while passing through town.

As Mother and Wife

In June of 1900, Susie’s older sister Lillie died, leaving the Caytons to raise their orphaned niece, Emma. Six months later, her father Hiram Revels died, and only a month after that, her mother passed away. It is important to note that Susie was also pregnant and gave birth to her second daughter, Madge, during this difficult time. After dealing with the deaths of his in-law’s, Horace returned to Seattle and found himself in the center of a controversy involving the Seattle police chief. Susie endured Horace’s arrest and lengthy trial.32 Due to a hung jury, the judge discharged the case, yet, as “The Part She Played” suggests, the experience may have shaken Susie. In that 1902 story, Susie introduces Mrs. Crosswaite as a lonely wife suffering from anxiety, headaches, and unhappiness in her marriage and ready to take extraordinary measures to convince her husband to refocus on the family. .

Perhaps it was in the regions of the heart where her trouble lay […] How it was only a short time since she could choose from several invitations where and how she would spend the evenings. Never a thought seemed to reach him of the happy home circle he had broken when he took her away to reign queen of his own home. It was enough to make her heart ache.33

While Susie’s dedication to her family never seemed to waver, her writing reveals the importance of black women’s roles in the family. As a mother, Susie Cayton gave birth to five healthy children, but raised seven; Emma, Ruth, Madge, Horace Jr., Revels, Lillie, and Susan. And in her reflection, many of the Cayton children’s destinies would take them down the path of their mother’s exemplary activism.

Perhaps one of the most difficult heartbreaks Susie endured was the death of her eldest daughter Ruth, in 1919. Ruth was a revolutionary in her own right, breaking from the ingrained moral principles of the family legacy. Susie and Ruth were very close despite the daughter’s choices in life. As her brother Revels relayed later:

…she made the most healthy adjustment of all of us children…And she was the first in our family to break away and seek full membership in the Negro community with no apparent thought about our family mission or the manner in which we had been raised.34

Susie had faith that Ruth would find her way and the young woman would go on to continue her part in the Cayton legacy. Unfortunately, Ruth was cut short from fulfilling her mother’s wish, and Susie became a mother to her infant granddaughter, Susan.

Susie Cayton raised her children with the vision of equality, education, and self respect as a tool to overcome the insanity of institutionalized racism. As a tool to combat the negative forces that met them when they went out in the world, Susie encouraged her children to take pride in their racial and family heritage by, telling stories of family memories, and stressed education as the key.

Madge Cayton, the second eldest of the Cayton daughters, took her parents advice and received a degree in Business Administration from the University of Washington in 1925.35 When Madge ventured out into the world, she faced the employment restrictions that prevented blacks from obtaining jobs in the professional fields. In the University of Washington interview, Virginia Clark Gayton recalled:

There weren’t any jobs for [educated blacks] even teachers and nurses couldn’t get jobs here either, but there wasn’t any of that… […]. There should have been some opportunity for …Negroes, but she [Madge] couldn’t find anything here.36

Despite her degree, Madge found herself limited by the constraints of white society, and resorted to taking sociology courses and moved to Chicago to embark on a career that centered on social work in the urban black community.

The Part She Played

Susie Sumner Revels Cayton died July 28th, 1943, in Chicago, where she lived with her daughter Madge after the death of her husband. Her remains were cremated and returned home to be scattered in the waters of Puget Sound. It is here where her husband’s ashes were scattered as well.37

Susie was the matriarch of the Cayton legacy and a driving force behind her family’s accomplishments. The forty-four years Susie dedicated to Seattle helped to define and assert African American identity in the black community as well as her family. As an educated black woman, the part Susie Cayton played as an astute writer was a voice that most likely would have gone unheard had she not had the success of the family newspaper to back her up. Like many of the social and political efforts of women during the early twentiethn century, especially ones married to prominent men, the legacy of Susie Sumner Revels Cayton has been overlooked in the chronicles of Pacific Northwest history. Susie was able to employ her political heritage and assert opinions that would have otherwise gone unheard to the dominant white society that had little interest in the opinions of African American women. The stories and essays left behind by Susie Cayton provide a window to the past to explore the complicated roles she played as a writer, wife, community activist, and mother in early twentieth century Seattle.

1 Susie Cayton. “The Part She Played”. Seattle Republican. 3 October 1902

2 Quintard Taylor. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press), p. 19.

3 Taylor, p. 5-7.

4 Taylor, p. 21.

5 Esther Hall Mumford. Seattle’s Black Victorians 1852 – 1901(Seattle: Ananse Press), p. 31-2.

6 Geraldine Cook. “Introduction.” Stories by Cayton, ed. Ed Diaz (Seattle: Bridgewater-Collins) p. 1.

7 Richard S. Hobbs. The Cayton Legacy: An African American Family (Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press), p. 9-10.

8 Hobbs, p. 4.

9 Buffalo Museum of Science, John Tevi, http://www.sciencebuff.org/john_tevi.php (accessed 10 Dec 2004).

10 Susie Cayton. “Negroes at the Atlanta Exposition”. Seattle Republican. 4 Jan 1896.

11 Hobbs, p. 21. Ch. 4, Note # 30. Interview with Revels Cayton and Bonnie Branch Hansen.

12 Susie Cayton. “The Land of Fire.” Stories by Cayton, ed. Ed Diaz (Seattle: Bridgewater-Collins) p. 55.

13 Ibid, p. 56.

14 “Stop Your Paper”. Seattle Republican. 26 Jan 1906.

15 Hobbs, p. 63.

16 Mary T. Henry. “Gayton, John Jacob.” 22 Apr 2002. HistoryLink.org, http://216.254.10.116/_output.CFM?file_ID=397 (accessed 10 Dec 2004).

17 Virginia Gayton, interviewed by Rich Berner, Tom McAllister, and Karyl Winn, African American History Project, Univ. of Washington, 16 June 1970, Transcript p. 15.

18 Ibid. p. 14.

19 Gayton, p. 15.

20 Ibid. p. 15.

21 Ibid, p. 14.

22 Richard S. Hobbs. The Cayton Legacy: Two Generations of a Black Family 1859-1976 (Univ. of Washington Dissertation, 1989), p. 190.

23 Horace Cayton Sr. “Good Woman’s Helping Hand.” Seattle Republican. 23 July 1909.

24 Hobbs, p. 76.

25 Quintard Taylor Jr. “Susie Revels Cayton, Beatrice Morrow Cannady, and the Campaign for Social Justice in the Pacific Northwest.” The Great Northwest: The Search for Regional Identity, ed. by William Robbins (Corvallis, OR: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2001) p. 32.

26 Sandra Haarsager. Organized Womanhood: Cultural Politics in the Pacific Northwest, 1840-1920 (Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1997), p. 214.

27 Mildred Tanner Andrews. Washington Women as Path Breakers(Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt, 1989), p. 46.

28 Tanner, p. 72.

29 Susie Cayton. “My Meeting with the Presence.” Stories by Cayton, ed. Ed Diaz, p. 63.

30 Ibid. p. 61.

31 Hobbs, p. 96.

32 Hobbs, p. 35-8.

33 Susie Cayton. “The Part She Played”.

34 Hobbs, p. 69.

35 Hobbs. The Cayton Legacy: Two Generations of a Black Family 1859-1976 (Univ. of Washington Dissertation), p. 214.

36 Gayton, p. 15.

37 Cook, p. 3.