Abstract: The Afro American Journal was published in Seattle from November 1967 to December 1972, and during that time was the most militant weekly newspaper to serve the black community. Supporting the principles of black power, the paper gave space to the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, and other activist groups. The Afro American Journal promoted community self-determination and had strong ties with the Black Culture Center while featuring extensive advertisements from black owned and operated businesses within the Central District.

In this report, Doug Blair examines the newspaper’s coverage of school and education issues in 1968 and 1969. Critical of the white-controlled school system and one-sided integration plans, the Afro-American Journal fought to give the black community control over the education of their children.

- Dates: November 1967 to December 1971, weekly, 5-8 pages.

- Circulation: unknown

- Editors: E. Loin and Taft Gross

- Address: PO Box 779 2348 East Cherry, Seattle

- Location of Research Collection: University of Washington, Suzzallo Library, Microforms and Newspaper Collection, A7076.

- Status of Collection:v.1 no.1-v.4 no.23 (Nov. 16, 1967-May. 27, 1971) Incomplete

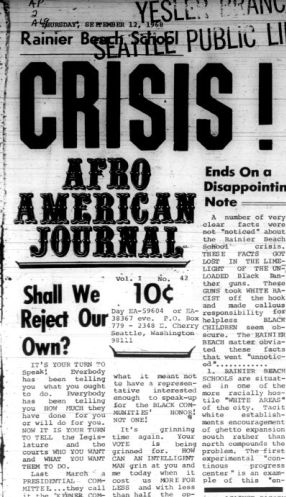

The first issue of the Afro American Journal, dubbed “Seattle’s Most Unique Weekly” was published on Thursday November 16, 1967. The paper continued as a weekly periodical until its demise in December of 1971. The Afro American Journal was sold for ten cents and began as a five page Thursday publication (occasionally the paper was issued on a Wednesday due to national holidays). Beginning with their first anniversary of publication, with issue in November 1968, the Afro American Journal expanded to eight pages. This longer format continued for the duration of the _Afro American Journal_’s run. The paper was edited by E. Loin and Taft Gross, although Taft disappeared from the roster in March of 1968. Very few of the locally produced articles are credited to any author (especially in the earlier issues), which suggests E. Loin or Taft gross were responsible for much of the early writing.

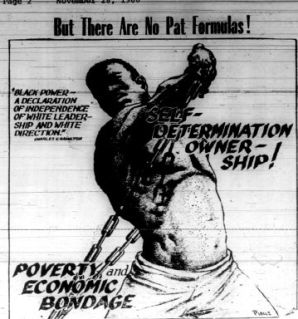

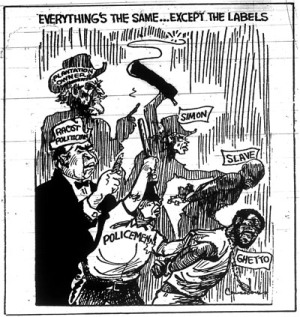

This report considers the paper’s coverage of education during its the first two full years of publication, 1968 and 1969. This time period is especially interesting because it marked a national shift from a black civil rights movement focused on non-violent action to more militant belief in black nationalism. While primarily focused on issues pertinent to the Seattle African American community of the Central District, other stories expanded the scope of the paper. News of the legal struggles of Black Panther leaders and other national black culture interests, for example, were common. The Afro American Journal openly supported the black power movement in the United States. Numerous articles were sharply critical of the white establishment, as well as prominent black politicians and celebrities, who the paper labeled “uncle toms.” Although not overtly militant, the paper offered a forum for the ideas of black nationalism and lent legitimacy to militant leaders of the black power movement. This close affinity to the ideas of black power and self-determination are clearly evident in the paper’s coverage of local education issues and the Seattle Public School system.

The education of black children in the Central District was the most salient theme of the Journal over these two years. Prominent headlines in large bold print, such as “Seattle Schools Sick” on July 18, 1968, demonstrated the growing frustration of the community with the Seattle Public Schools neglect of black children. The integration crisis and struggle for more black representation in Seattle’s public schools was certainly a hot issue. During an eight-month stretch starting in April of 1968, there were one to three articles per issue pertaining to the issue of education. Although most of the articles were locally produced, occasionally a national perspective on education of black youth was also provided. The most notable example of this national voice was a weekly syndicated column by Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) national director Floyd McKissick that often related to education during this period.

Leading the _Journal_’s local education coverage was Cliff Hooper, an outspoken member of the Seattle black community and frequent contributor (the only author consistently credited throughout 1968 and 1969) to the Afro American Journal. In the most consistent series of articles in the entire run of the Afro American Journal, Hooper confronted the problems surrounding the education of black youth in Seattle and the United States. His weekly column entitled “Education,” began in the July 11, 1968 issue and continued well into 1970 (although less frequently) with similar themes. Hooper was primarily concerned with whites’ inequitable control of the public school system and Seattle’s lack of black teachers and administrators. Hooper advocated for greater oversight in the education of black youth by the black community. The following selections from the early months of Cliff Hooper’s column contain some strong sentiments, and clearly illustrate his position (as well as the position of the Afro American Journal) on the state of education in Seattle.

“The school officials, well endowed with backgrounds in white mythology, do not seem persuaded that the crime of messing over the minds of our youth is out. As a black administrator on a recent TV program pointed out, “we have grave reasons to be concerned with a system (white education system) that takes our children of normal aptitude and gives them back to us twelve years later unable to read.”” (July 11, 1968: Pg 3)

“Our children must have the umbrella of BLACK AUTHORITY- just as naturally as every white child has WHITE AUTHORITY- as the upward pulling force, like moisture is pulled towards the sun. A BLACK ETHNIC STATUS COORDINATOR must be out into the Seattle Public School System effectively staffed and responsive to the BLACK COMMUNITY.” (July 25, 1968: Pg 3)

“The black community MUST make decisions in the education of its 11,000 sons and daughters at every level – staffing, finances, curriculum, physical planning, athletic programs – the whole bit! Any further mistake in educating Black youth must become the privilege of the Black community and the taking of this responsibility must not be further delayed.” (August 1, 1968: Pg 3)

“It must be conceded that generally white people raise white children and black people raise black children, then let it be so. White power is the only power making decisions on the education of Black Youth in the public schools in Seattle and it projects an arrogant image. It presupposes that white people know best.” (August 22, 1968: Pg 5)

“Barring the miracle that never happens, Seattle’s Black youth will continue to be processed through a system that fails to thoroughly explain where they have been, where they are and where they are going.” (October 24, 1968: Pg 7)

“Each year of this writers life has strengthened the view that ANY capability that white people may have to educate Black children is not readily apparent.” (October 24, 1968: Pg 7)

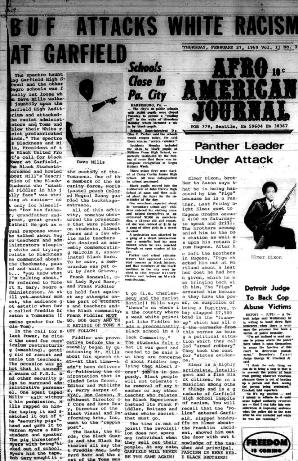

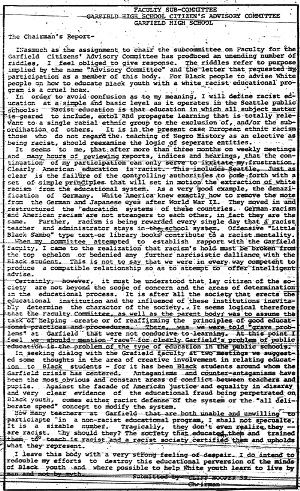

The black power movement was especially prevalent at Garfield High School, where Stokely Carmichael had delivered a speech in Spring of 1967. After his attempt to prevent Carmichael from speaking in the school auditorium, Principal Frank Hanawalt came under intense pressure from black militants. Hanawalt eventually resigned from Garfield in January of 1968. Hoping for a black principal, the Afro American Journal was highly critical of Hanawalt’s white replacement, former physical education teacher and vice-principal Frank Fiddler. As the paper editorialized, “It takes bravado for a White principal to come to a Ghetto School and denounce Black Power as Separation” (March 21, 1968: Pg 3). In an effort to regain control over Garfield, Fiddler instituted restrictive policies designed to quell the growing support for black nationalism (March 21, 1968: Pg 1).

The Afro American Journal also gave front-page coverage to an incident at then predominantly white Rainier Beach High School in September of 1968. A group of Black Panthers showed up at Rainier Beach armed with guns (allegedly unloaded) in an effort to protect the small black student body. There had been a series of violent incidents where a number of white students had ganged up on blacks. According to the article, “We can find NOT ONE REPORT on WHITE PARENTS CONCERN for the severely beaten BLACK YOUNGSTER— only indignation that their children saw BLACK MEN in “their” school (instead of VIET-Nam) with guns” (September 12, 1968: Pg 1). As a result of this and other incidents, on September 23, 1968 the Seattle City Council passed a measure that banned the display of weapons for the purpose of intimidation1.

The struggle for greater black control over central area schools again boiled over in a series of riotous incidents at Washington Jr. High in September of 1968. Again, the Afro American Journal criticized the school’s decision to temporary close the school on September 25th. The paper was attentive to the hypocrisy of the closure, noting that, “that no one was seriously injured in the episodes that led to the closing of Washington Junior High School, but it was a sock in the jaw to the black community… By contrast at Rainier Beach High School, a Black child was brutalized by white people and such extreme action was not taken at Rainier Beach, as serious as a closure” (October 3, 1968: Pg 5).

The issue of school integration also received frequent coverage by the Afro American Journal. At the center of the integration controversy was a plan that forced central area youth to bus to traditionally white schools in surrounding neighborhoods. As one parent of a Horace Mann Elementary student was quoted, “What it amounts to is that I’m paying for my child to attend a “white” segregated school 20 miles from my home and a school segregated by “Negroes” 150 feet away from my home is being neglected and it’s not fair (February 22, 1968: Pg 1)”. Central area residents did not believe their black children should bear the burden of integration in public schools. One front page column described a disorderly scene when the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle proposed the closure of several traditionally black central area schools, including Horace Mann Elementary, Washington Jr. High, and the reduction of services at Madrona Elementary and Garfield High. A meeting at the East Madison YMCA to unveil the plan became so contentious, the paper reported, it was adjourned prematurely due to fears of unrest and protest (March 7, 1968: Pg 1).

The Afro American Journal entered the mainstream political arena when it advocated the defeat of a school levy slated for the November 1968 election. “BLACK PEOPLE HAVE NOTHING to lose and a lot to gain by helping defeat the SCHOOL LEVY on Nov. 5th” (October 17, 1968: Pg 1). According to the paper, the levy would only reinforce the unfair system under which black children took the responsibility and inconvenience for public school integration. The neighborhood school proposal under the levy was to maintain current segregation levels while placing higher priority on schools in white areas of Seattle. With forceful language, the paper argued “THE BLACK CHILD IS THE PAWN in a white racist game of miseducation and sophisticated double talk for which the Black family is ask (sic) to pay for” (October 31, 1968, p1).

The Afro American Journal offered continued coverage of the newly formed Benjamin Banneker School in the fall of 1969. The Banneker School was run out of the the Black Culture Center (Headed by frequent Afro American Journal contributor Keve Bray) and offered black youth an alternative to the racist public schools. As the newspaper reported, “The curriculum is structured to make Black youth hard working productive members of the black community with a goal of obtaining unity and excellence. It was the hope of the school’s organizers that personal sacrifice and dedication would allow the community to confront the public schools and issue a strong challenge to the status quo (October 30, 1969: Pg 1). The Banneker School used the Black Culture Center as a forum for displaying arts and crafts made by students, as well as hosting community feasts and other gatherings. In an effort to promote black community education (as well as a bit of fundraising), the school began producing blackboards for sale in the central area community (November 6, 1969: Pg 6). Although other articles from the Afro American Journal in the fall of 1969 still reflected a negative tone in regard to education in Seattle, the Banneker School pieces offered hope for change.

The Afro American Journal was a short lived publication during a time of great social turmoil for the black community in Seattle and the United States. The paper offered an Afro-centric perspective, providing stories of prominent blacks around the globe. The paper supported black nationalism and advocated that blacks control their own lives and services. No issue mattered more than education. The Afro American Journal’s coverage of the crisis in Seattle’s public schools provide an excellent window into that volatile and complex time.

©Copyright Doug Blair 2005

HSTAA 353 Spring 2005

1 Walt Crowley, Rites of Passage: A Memoir of the Sixties in Seattle (Seattle, 1995)