Arrested in 1949 and facing deportation, Ernesto Mangaoang’s four-year fight to remain in the country he had entered legally twenty-seven years earlier resulted in a landmark court decision that clarified the status of 70,000 Filipino Americans who had immigrated during the era of US colonial occupation of the Philippines.

At the height of the American colonization of the Philippine Islands in 1931, Ernesto Mangaoang, a Filipino-American national, issued a fervent cry for his people’s right to simply “be” in the country that they called home. Titled “Filipinos Want Equal Rights or Independence,” Mangaoang’s letter to the editor in The Oregonian recorded acts of discrimination and persecution: “Last fall I was thrown out of a job just because a white man wanted to get it.” He was angry, asserting that if the United States “insists that the Filipinos remain under the American flag, we don’t want to surrender our right to live in this country.” [1] He then made an intriguing suggestion. If white Americans believed that that the “Filipinos constitute a menace to her own economic welfare,” the U.S. should grant the Philippine Islands independence “so that they could be barred from entering this country,” a reference to restrictive immigration quotas developed by an isolationist United States. Until this freedom is granted, Mangaoang argued, Filipino Americans have the right to live in the United States. In this short letter to the Portland newspaper, Mangaoang eloquently described the disparity of the Filipino experience in the United States: a second-class citizenship characterized by the vague status of "American national" that produced widespread discrimination, both in the workplace and at home—any spaces where Filipino-Americans asserted their right to be.

Twenty-two years after his letter decried the unique and unjust predicament of Filipino-Americans, Mangaoang, a cannery worker turned labor leader, would be at the center of a pivotal court case. The 1953 decision of the Ninth Circuit Court not only affected him and the 70,000 other Filipino-American nationals at the time; it highlighted the hypocrisy of imperial America and exposed the uncertain rights of America's colonial subjects.

It began four years earlier. Tucked beneath a headline about a fire that devastated a local Tacoma inn, the front page of the August 1, 1949 edition of the Seattle Times read: “Union Leader Arrested,” an arrest based on the Immigration Act of 1918. [2] The union leader was Ernesto Mangaoang, a World War II veteran, and a U.S. national. The Immigration Act gave the Secretary of Labor authority to deport aliens with Communist ties. Citing this Act, the U.S. Department of State issued a warrant for Ernesto Mangaoang’s arrest for his earlier membership in the Communist Party. [3] But Mangaoang was not an alien. Born in the Philippines in 1902, Mangaoang journeyed to the United States in the 1920s, arriving in Seattle, Washington as a “lawfully admitted… permanent [resident].” He was not an alien when he arrived in the United States but the Justice Department said that he and 70,000 Filipino Americans had become aliens in 1946. Mangaoang’s legal battle would not be straightforward.

The obstacles and setbacks that Mangaoang and attorney John Caughlan faced perfectly reflected the inequities and hypocrisies of how Filipino-American nationals were treated by the U.S. government. Mangaoang was detained without reason, his petition for a writ of habeas corpus was denied, and he faced multiple administrative hearings without counsel. [4] Despite the unjust treatment and lack of due process, Mangaoang successfully fought for his right to stay in the United States and in doing so clarified the status of the thousands of Filipino-Americans who emigrated during the colonial era.

This David-and-Goliath story is not just about one extraordinary man. It also highlights the ability of a marginalized group to reclaim their rights from the federal government by accessing both diverse and divergent resources. Mangaoang’s unlikely victory on appeal to the 9th Circuit Court was supported, in both financial and tactical regards, by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born, the Local 7 cannery workers union that Mangaoang led, and the legal ingenuity of labor rights’ Attorney John Caughlan.

The Meaning of a Filipino-American National

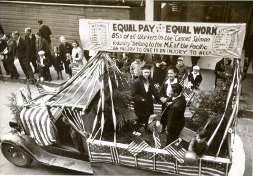

As a result of the United States’ colonization of the Philippines from 1902 to 1946, Filipinos sought education, improved work opportunities, and a better life in the United States. Unaffected by immigration restrictions that barred immigration from other Asian countries, there were over 98,000 documented Filipino-Americans living in the United States by 1940. [5] Two pivotal court cases in the early years of the 20th century determined that Filipinos would be considered “American nationals” -- non-citizens, yet still under the purview of a U.S. colonial government. The refusal to extend citizenship was indeed a racialized one: Filipinos were viewed as savages, incapable of self-government, and “irreconcilable with the U.S. nation state.” [6] Island territories like Puerto Rico and the Philippines, the courts held, were never intended to be fully incorporated like the former territories of Louisiana and California had been. 7 Thus, the convoluted status of an American national entered the legal, political and public sphere: peoples who were subjugated to U.S. colonial rule but determined racially inferior and therefore underserving of constitutional protections and guarantees.

Throughout the decades that the Philippines remained subject to U.S. colonial rule, attempts to define the rights of an American national were juggled in the legal system. A 1917 ruling by District Court Judge William found a Filipino-American national, Engracio Bautista, both an alien and an American national under multiple legal statutes. 7 While Bautista was granted naturalization under a 1906 clause that provided a pathway to citizenship via military service, a prior case determined Filipinos were excluded from naturalization as a result of racial restrictions established under that very same law. 7 Contradictions such as these marked the experiences of allFilipino-American nationals, who at best, could claim inconsistent rights and liberties on the American mainland.

Barred from accessing citizenship, yet generally unrestricted from coming to the U.S. mainland to make a living, Filipino-American nationals experienced the withholding of certain liberties and rights as a result of their non-alien but non-citizen status. In Dorr vs. U.S. (1904), the Supreme Court struggled to draw a clear line as to which rights’ Filipino-American nationals were granted, and which were outside the realm of a non-citizen. The Court declared that colonized peoples such as Filipinos deserved certain guaranteed fundamental rights, which were broadly understood as the rights protected by the First Amendment and the right to private property. Other rights, such as a trial by jury and enfranchisement, were deemed “non-essential.” [7]

In 1925, the Supreme Court decision Hidemitsu Toyota v. United States denied naturalization to the plaintiff, who was born in Japan and completed honorable service in the U.S. Navy. This case was significant for Filipino-American nationals because the justices, in their opinion, determined that Filipinos, like Japanese aliens, were racially ineligible for citizenship. What set them apart, the opinion continued, was that Filipino-American nationals owed allegiance and loyalty to the U.S. government, and therefore could be considered for naturalization only after the competition of honorable service in the U.S. military. This decision confirmed Congress’s intent “[to] limit the naturalization of aliens to white persons and to those of African nativity…” [8]. These influential Supreme Court decisions confirmed Filipino-Americans status as second-class, and their inferiority became cemented into law.

In the 1930s, two new federal laws further narrowed the rights of Filipinos. The Hawes-Cutting Act, enacted in 1933, prevented all Filipino American nationals from accessing citizenship and restricted the number of Filipinos who were permitted to emigrate to America to a mere one hundred people per year. [9] The Tydings-McDuffie Act, passed in 1934, set a timetable for Philippine independence and changed the status of Filipinos in the United States. Stretched out along a ten-year timeline, the Act explicitly noted that Filipino American nationals “…who are not citizens of the United States shall be considered as if they were aliens…” upon the country’s independence. [10] The quota established by the Hawes-Cutting Act was slashed in half: independence meant that only fifty Filipinos would be permitted to immigrate to a place that many considered home.

Lengthy hearings followed the passing of the Tydings-McDuffie Act as a result of the negative impacts on Filipino-American nationals that resided in the United States. Many Filipino American workers were barred from union participation following the Act’s passing. In a 1939 hearing defending Filipino Americans’ right to union involvement, Dr. B. M. Gancy, director of the Filipino League for Social Justice, spotlighted the human cost of such a law. 3,000 Filipino-American nationals were barred from jobs they held in the merchant-marine service because it was restricted to citizens. Filipino-American industrial and seaboard workers were immediately fired. In particular, he noted, mixed-race families in dire economic straits were being denied government -- and even charitable assistance because of their newfound ‘alien’ status. “Filipinos are not alien,” Dr. Gancy continued, “Filipinos to this day and until they are finally granted their coveted independence owe complete allegiance to the United States. They are subjects of the United States and they are in law ‘American nationals.’” [11] The Tydings-McDuffie Act “contain[ed] no provisions for the welfare of Filipinos residing in the United States. Finally, Gancy noted, that most of [the 65,000 to 75,000 Filipino Americans] had no desire to return to the Philippines…” and, even more notably, “they [were] more at home in this country of their adoption.” [12] The Tydings-McDuffie Act set an expiration date on Filipino-Americans’ already delicate status asAmerican nationals. Ernesto Mangaoang was determined to prove that American nationals could not be relegated to an alien status, despite the skyscraper barriers posed by the new laws.

Political attitudes did not sway in Mangaoang’s favor, either. In the late 1940s, as the United States and the Soviet Union faced off in an escalating Cold War, anti-Communist sentiment in the United States increased exponentially. Congressional investigations found that Communism “[was] a world-wide revolutionary movement whose purpose it is, by treachery, deceit, infiltration… espionage, sabotage, terrorism, and any other means deemed necessary, to establish a Communist totalitarian dictatorship in the countries throughout the world…” [13] Starting in 1947, the U.S. government moved to suppress those associated with Communist groups, circumventing many First Amendment guarantees along the way. [14] Foreign-born Communists and former Communists were especially vulnerable. Non citizens faced deportation.

Ernesto Mangaoang, in brief

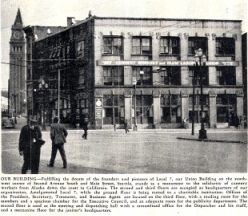

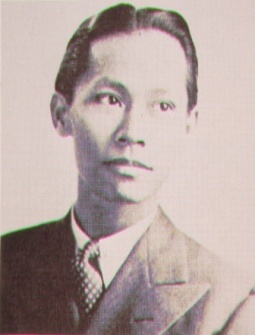

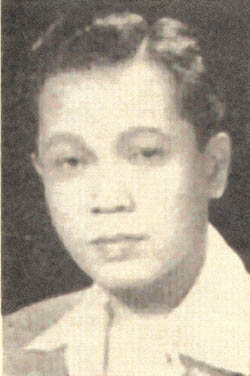

Ernesto Mangaoang arrived in the United States when he was twenty-two years old, with the hopes of becoming a lawyer or doctor. Immediately, he was dissuaded as he was told that people who looked like him did not “get to wear white suits.” [15] He worked in agriculture, like many Filipino-Americans, and started off his career harvesting lettuce -- a backbreaking and low-wage job. Making his home in Oregon in the late 1930s, Mangaoang became involved in union organizing joining and then leading Local 266 of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA) labor union. It was unique in its inclusion of Black, Asian-American and Latino workers, and at its core fought for workplace equality for those minority groups forced to the periphery. [16] In 1944 he was elected President of the local and helped negotiate the merger of the Seattle and Portland cannery workers locals which then became Local 7 (UCAPAWA). Moving to Seattle, he was elected Business Agent of the combined local.

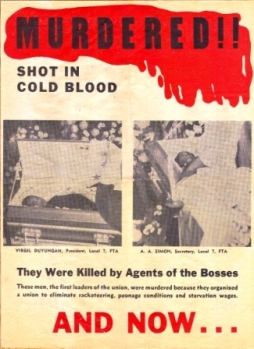

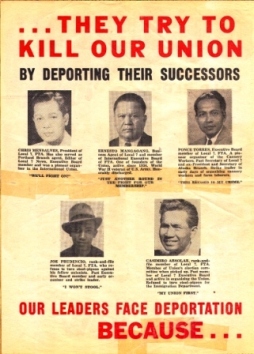

Mangaoang had joined the Communist Party some years before, as had several other Local 7 leaders, including Chris Mensalvas who would become president of the local in 1949. The local’s reputation as a leftwing union became an issue when Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, requiring unions to ban Communists and former Communists from leadership positions. Local 7 and its parent union were expelled from the Congress of Industrial Organizations and came under government scrutiny. The cannery union found help and a refuge in the powerful International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) which had also been expelled. In 1949, local 7 became an ILWU affiliate and was later renumbered as Local 37. Ernesto remained a leader in Local 37, serving as its Business Agent even as he faced his own legal struggles. He would remain in that position until in 1954 when he was forced out as a result of fundamental disagreements among factions within the union. [17]

Deportation Attempts, Part I and II

Following the trail of Mangaoang’s multiple arrests by the Immigration and Naturalization Service is not easy. He was arrested and jailed no less than four times, and each time the government tried to deny him bail, insisting that he should be held in jail through hearings and trials. His attorneys did manage to win habeus corpus rulings eventually and win his release under conditions of very expensive bail, but altogether he spent 83 days incarcerated. His first arrest occurred in August 1, 1949 under Section I of the Immigration Act of 1918, which granted the Secretary of Labor the ability to issue a warrant for the arrest of “alien anarchists… and similar classes.” [18] His bond was set at $5,000-- around $53,000 in today’s dollars. Attorney John Caughlan took Mangaoang’s case, and he immediately penned a letter to John Boyd, the District Director of the Immigration and Naturalization Services, requesting that Mangaoang’s bond be lowered to no more than $2,000. Caughlin pointed out that Mangaoang intended to “resist the charges which have been filed against him”, and that the bond should merely act to ensure Mangaoang appears in court. In this letter, Caughlan sought to humanize Mangaoang, citing his honorable discharge from the U.S. Army, his employment position as an officer of the Local 7-- “a responsible post”, and illustrated Mangaoang as a community member-- spending the entirety of his adult life in Portland or Seattle. [20] Caughlan’s request was denied, and Mangaoang was released for the first time on a $5,000 bond, funded and raised by the Local 7. Caughlan noted that Chris Mensalvas, the Local 7 Union president who had been arrested a few weeks later under the charge of Communist party membership, was left with no funds for his bond as a result of the undue expense. [21]

Mangaoang's second arrest came four months

later and here too he managed to win release while the amount of bond was doubled to $10,000. [22] Meanwhile four other members of the Local 7 leadership had been arrested on similar charges. Chris Mensalvas, Ponce Torres, Joe Prudencio, and Calimiro Absolar now joined Mangaoang awaiting INS hearings to determine whether they should be deported to the Philippines. Their union struggled to find bail money and the means to defend its leaders. Then things got worse. In September 1950, Congress passed McCarran Internal Security Act. In the first “invocation of [the

McCarran Act in Seattle]”, Mangaoang was rearrested

and placed in county jail as a part of the Justice Department’s “roundup of top

alien Communists.” [23] The McCarran Act granted new powers to the Justice Department to go after radicals, including allowing federal officials to round up suspected “alien

Communists” without warrant, and to detain such persons for a period up to six months, virtually immune to habeas corpus petitions. Further, if the detainees could not be deported

within the six-month timeline, “the law directs that they be kept under close

supervision by the Immigration Service.” Immediately, attorney John Caughlan alerted the Seattle Daily Times that

he would be pursuing a writ of habeas corpus to free Mangaoang from custody.

The days and weeks that followed the

passing of the McCarran Act were filled with short-lived victories. Initially,

District Judge John C. Bowen ruled that Mangaoang had

been illegally arrested because the Service’s warrant had expired. [24] Mangaoang was freed on a writ of habeas corpus just four days after Caughlan announced his intentions to file, however, John Boyd, announced Mangaoang would be rearrested “immediately upon [his]

release, on new warrants issued by the Immigration Service…” [25] In an almost celebratory manner, Boyd recognized that Mangaoang’s warrant “was the first issued in the nation under the new [Act].” [26] Mangaoang’s second attempt at a writ of habeas corpus was denied when District Judge Bowen

proclaimed: “…there is insufficient concern for the continued safety and

security of the nation,” , which suggests that Mangaoang’s implicated Communist party involvement was a

matter and threat to national security. The Seattle Times refers to Mangaoang’s situation as the “first case of kind” [27],

which, looking back, foreshadowed the groundbreaking legal journey and impact

that followed. Nearly a month after his re-arrest

by a warrant issued under the McCarran Act, Mangaoang was denied freedom a third time. Attorneys Barry Hatten and John Caughlan sought Mangaoang’s release in order to prepare legal arguments for his upcoming deportation

hearing. [28] Caughlan refused to give up on his client-- he responded, just two days later, by filing

an appeal for habeas corpus to the Ninth Circuit Court-- Mangaoang’s first appearance at the higher court, and certainly not his last. This appeal

was also denied, as Judge Bowen declared that Mangaoang “properly could prepare his defense while in custody” [29],

further circumventing Mangaoang’s legal rights.

Ironically, the Seattle Daily Times reverses their terminology applied

to Mangaoang, calling him a “Filipino national” rather than an alien,

highlighting the complexity and lack of understanding that surrounded the

identity of Filipino-Americans. One of the more remarkable

occurrences throughout Mangaoang’s legal battle was

the coming together of union and civil liberties allies in his defense. A number of organizations

that defended the working class, non-citizens, and people of color supported Mangaoang’s case from the very start, as the Local 7 raised

bond funds after his first arrest. [30] Mangaoang sought further assistance from union

organizations as his deportation hearing approached. After the renamed ILWU

Local 37 union filed an amicus curiae brief in Mangaoang’s favor, he penned a letter to Bill Gettings, the regional director of the International

Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union, requesting a second amicus curiae brief from the international union’s attorneys in San Francisco. [31] The ILWU brief was powerful, as it detailed the “injustice and illegality

of the attempt to deport persons who came to the United States as nationals…

who have owed allegiance to the United States ever since they first arrived.”

The American Civil Liberties Union

(ACLU), a non-profit organization that utilized legislative and legal avenues

to protect the rights of marginalized communities, also joined in Mangaoang’s fight. They recognized that Mangaoang’s deportation at the hands of the Attorney General, “merely because he was a

member of a class of persons (allegedly a Communist)” posed a threat to the civil

liberties of Filipino-Americans and potentially others. [32] Associate Staff Counsel at the ACLU, George Soll, urged the Executive Secretary

of ACLU’s Seattle chapter, Max Nicolai, to become involved in Mangaoang’s case, imploring that, “the issue is of

sufficient importance to justify our submitting an amicus brief just on [the

denial of habeas corpus and suspension of bail].” The vast power granted to

Attorney Generals by the McCarran Act became a call to action for the ACLU in

order to protect the freedom of belief, expression and association for those

with unpopular political associations. Yet another group committed to

defending the rights of minoritized groups living along the peripheries of the

American politic, the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born was

founded by Roger Baldwin of the ACLU. They focused on “defend[ing] the constitutional rights of foreign-born persons in

the United States.” [33] The group worked closely

with the International Labor Defense, the legal division of the Communist

Party. [34] The Pacific Northwest arm

of the ACPFB formed in 1949, exactly a month prior to Mangaoang’s initial arrest. The Daily People’s World, a newspaper founded and

supported by the Communist Party, excitedly reported the following: “Elected as

board of directors were…Ernie Mangaoang and Marion

Kinney, vice chairmen.” The committee formed to “protest against illegal fear

tactics of the United States Immigration Service.” [35] The featured speaker

--Attorney John Caughlan-- would fight tirelessly for Mangaoang’s freedom. Mangaoang committed his efforts and leadership to protecting non-citizens who risked

deportation for exercising their political voice; it comes as no surprise that

this organization came to his aid when he found himself in the very same battle

as those he defended. In

1951, the Northwest arm of the ACPFB hosted a “Northwest Conference to Fight

Deportation”. Dinner was served in honor of the incarcerated victims-- Mangaoang’s name listed along with nine other members of Local 37. Among

their conference goals was to “send a relative of one of the deportation

victims to Washington, D.C., the week of March 19th, to join other relatives from

all over the [U.S.] to protest, in person, the wrecking of homes and friendship

ties of those innocent people.” The conference attendees

accuse “the ‘Justice’ Department, not our deportation victims” of circumventing

“… the Constitution of the United States in its attempt to enforce the

unconstitutional McCarran Law.” [36] In addition to supporting Mangaoang and others in his

situation, Abner Green, the executive secretary of the ACPFB, remained in close

contact with attorneys Caughlan and Hesse throughout Mangaoang’s legal journey. He signed off a July 3, 1953

letter to Siegfried Hesse with congratulations upon their eventual victory: “I

assume the government will appeal and also try to

amend the Law. But, even if we lose in the long run, this victory is important

and, as long as it lasts, crucial.” [37] As the government mounted their case

against Ernesto Mangaoang, his chances of victory

would have been much reduced without the support of groups fighting to

protect civil liberties for all, regardless of their citizenship status or the

color of their skin. The contributions of unions, the ACLU and the American Committee for

Protection of Foreign Born are an important reminder of the importance of

organizations who are willing to protect the freedoms of those at the

fringes. Continuing the crackdown on those with Communist affiliations, Boyd received direct

orders from Washington D.C. for Mangaoang’s immediate

deportation on August 9, 1951, after Seattle hearings confirmed Mangaoang’s connections with the Communist Party. Given

fifteen days to appeal the decision, Mangaoang and Caughlan jumped into action. [38] Caughlan wrote to Richard Gladstein, a San Francisco labor

lawyer, outlining their legal argument in a request for an amicus

curiae brief. [39] They were determined to

establish Mangaoang’s status as an American national,

because “as a national, he would not be subject to deportation.” [40] The language in the

McCarran Act provided for the deportation of “aliens who are members of the

Communist Party.” [41] The present tense “are” would be a pivotal argument for Caughlan and Mangaoang and the Local 7 leaders. John Caughlan contended that the McCarran Act did not apply --

writing that “none of the Filipinos who are or have been arrested on political

charges are alleged to have been members of the Communist party since the

independence of the Philippines [in 1946].” [42] Caughlan had hope, as he concluded his letter,

saying, “…we feel that we are on very solid ground.” [43] His appeal was dismissed

by District Court Judge McLaughlin, who had previously ruled, in 1949, that

Filipinos were indeed aliens. The Board of Immigration Appeals’ special inquiry

board upheld the decision surrounding Mangaoang’s deportation, one of ten cases heard for a second time under the McCarran

Act. Mangaoang’s deportation was scheduled “at 10 o’clock on January 2 [back] to the Philippine

Islands.” [44] Undeterred

by two years of government victories, Attorney Caughlan asked “the U.S. District Court to review [Mangaoang’s]

immigration hearing…” the very next day. [45] Caughlan fought to increase Mangaoang’s odds of victory,

having petitioned the Board of Appeals “to stay all proceedings while the board

reconsiders the case.” Refusing to give up, Caughlan explored another legal avenue, as he announced he would “[take the case] into

Federal Court.” [46] Caughlan’s dedication to Mangaoang’s fight was notable, as they

pressed forward when precedent suggested an outcome in Mangaoang’s favor would be an impossibility. Caughlan and Mangaoang’s stay was granted, as his scheduled deportation

was halted in order that his case be heard by U.S. District Judge William

Lindberg. [47] The

chance of freedom again came crashing down as Mangaoang “lost another round today in [his] fight to remain in the United States.” [48] His writ of habeas corpus

was, yet again, denied. The Seattle Times headline read, “Deportation

Fight Lost by Mangaoang.” [49] Mangaoang,

who had been freed on a union-fundraised bond, was taken back into custody,

disrupting his labor-rights work. Detained multiple times when he clearly posed

no national security threat, Mangaoang’s situation

reflected the prioritization of government interest over individual liberties.

Especially in consideration of Mangaoang’s uncertain

status, his access to rights was of lesser importance in the eyes of the U.S.

government. Caughlan responded to this devasting blow

by asserting that Mangaoang’s case would be appealed

to the Ninth Circuit Court, as he refused to stop fighting for Mangaoang’s freedom. [50] With

an appeal to file, there was work to be done. Caughlan penned a memorandum to Ernesto, as well as William Gettings, Regional Director of the ILWU, as encouragement

that their battle was worth pursuing and persevering, despite the hardships the

team experienced. He urged Mangaoang that his story--

his case-- mattered. “This [is] the first court challenge of the [deportation

provisions] of the McCarran Law,” Caughlan wrote. In

sticking through, they would be trailblazers. [51] Further, Caughlan noted, Mangaoang’s case

was the first to “[raise] the question of whether a Filipino is deportable for

acts done while he was a national of the United States.” [52] A messy question, Mangaoang’s fight helped call attention to the issues that

resulted from the ambiguity of the American national status. To what extent,

they questioned, did American nationals have rights to political expression?

Finally, Mangaoang’s case was worth fighting for in Caughlan’s eyes because of its massive implications for

union and workers’ rights. “There are several thousand Filipino members of the

International Longshore and Warehouse Union… the Immigration Service has

commenced a real union-smashing drive amongst Filipinos, particularly in Local

37…” Caughlan wrote, as he highlighted the broader

possibilities for a victory by Mangaoang. “[We] are

in communication with [firms] who represent Filipinos facing the same charge,” [53] encouragement that Mangaoang’s fight for freedom might impact

Filipino-American union leaders and members throughout the country. With

aspirations to defend the rights of unionization and expression of

Filipino-Americans, Ernesto Mangaoang and his team of

attorneys filed their appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court on July 18, 1952. [54] Ernesto Mangaoang’s Ninth Circuit hearing began on December 5, 1952-- decidedly his last chance to

secure his own freedom and in the words he had penned in 1931, his “right to be.” In Caughlan’s presentation of the case abstract to the

Court, he underscored Mangaoang’s illegal detention

at the hands of the Immigration Service, alerting the Court to a “purported

deportation hearing held by the Immigration Service… [with] inadequate notice

and consideration… of counsel.” [55] Consequently, Caughlan argued, Mangaoang was

forced to defend himself at his own deportation hearing, without representation

by legal counsel. Because deportation hearings are considered civil, not

criminal cases, the accused are not guaranteed counsel by the Constitution.

Ironically, lengthy detention sentences treat those facing deportation more

akin to criminals. Mangaoang’s situation mirrored

countless deportation hearings witnessed today under the Trump administration,

where “…it’s life or death for a lot of these people, for these members of our

community. Just because they can’t have access to counsel, they get deported

and… separated from their families.” [56] Of the nine errors that Caughlan declared the District Court committed, perhaps the

most damning were that the District Court had “erred in concluding that [Mangaoang] had not been deprived of due process of law,”

and further, the Court had erred “in concluding that the Internal Security Act

of 1950, in so far as it renders membership in the Communist Party [as] a

deportable act, is a constitutional enactment.” [57] He doubled down on the

language in the McCarran Act statute, which called for the deportation of

“aliens who are members of… the Communist Party of the U.S.” Mangaoang’s Communist Party membership between 1938-39, and

his status as an alien, established upon the Philippine’s Independence in 1946,

made it impossible for him to have been both an alien and a member of the

Communist Party. [58] Caughlan’s defense hinged on three main arguments: Ernesto Mangaoang had a right to political expression, a right to be or live in the United

States, and a right to due process. As an American national, Mangaoang has a right to political expression, one of the

fundamental rights that protect nationals, as well as citizens, from

government-driven censorship. Caughlan contended that

the McCarran Act made “mere membership in the Communist Party a deportable

act,” which constituted “guilt by mere association, [a violation of] due

process of law.” [59] Caughlan established that Mangaoang was entitled to live in the United States when he

declared that, “expatriation is a matter of intent… [Mangaoang]

came to this country as a matter of right.” [60] Additionally, Caughlan noted, Congress was “without power to deprive [Mangaoang] of [his status as an American national].” [61] In Caughlan’s legal perspective, Ernesto remained a national to this day, regardless of the

Philippine Island’s independence. Further, he posited, “the power to deport is

implied from, and depends upon, the power to exclude.” [62] Since Mangaoang entered the U.S. freely, as a

national, without restriction, he was not excludable, and “he cannot,

therefore, be deported.” Caughlan then moved to convince the Court of their duties to acknowledge the

complexities of the Filipino-American status. “Expatriation,” he declared, “is

a fundamental right of all human beings… this… is a principle that has been an

integral part of our… government since the 1776: freedom from oppression and

expatriation are concurrent essentials for humanity.” [63] Caughlan implored that Mangaoang’s right to build a better

life for himself in the United States, especially as a national, was integral

to the nation’s values. The act of making Mangaoang “an alien against his volition” stood at odds with American values of freedom,

liberty and self-sufficiency. [64] He reminded the judges of

the human cost of forced deportation: Mangaoang “[had] lived and worked here as a part of the American community, for over 26

years. He is now told that involuntarily… he is to lose the nationality he

obtained by birth, and be deprived of ‘all that makes

life worth living.’” [65] Mangaoang had attempted to secure his right to be in the United States by applying for

citizenship after completing his military service, only to be denied. [66] Caughlan positioned Mangaoang’s struggle as something greater

than battling deportation, this was about securing an identity and belonging

for a group of people whose lives were in upheaval after being renamed as

"aliens". Boyd

responded to Caughlan and Mangaoang’s claims by stating that “this court… has definitely settled the question as to

the political status of Filipinos, so that further argument on this point, it

would seem, is not necessary.” [67] He sought to silence Mangaoang and Caughlan by

declaring the incredibly complex issue of Filipino-American status as decidedly

finished. To Boyd and others, the livelihoods of over 70,000 Filipino-Americans

deserved no further debate. In

regard to the violation of due process by the Immigration and Naturalization Service,

Boyd pointed to the struggle between “the interests of the Government as the

protector of the public interest,” and “the requirements of fair hearing.” [68] While Boyd identified a

legitimate struggle between public security and individual civil liberties, Mangaoang’s indefinite detentions without legal reason was

an extreme response in the name of public interest. Boyd also highlighted Caughlan’s “[refusal] to cooperate in any manner with the

Government…”, reflective of Caughlan’s protest-like

approach to his defense. [69] In Mangaoang’s extraordinary case, one could posit that actions of protest were necessary to

prevent swift deportation in the hands of the government. Boyd

closed his argument on behalf of the government by attacking Mangaoang’s right, as a national, to associate with the

Communist Party and other extreme groups. He postulated that Mangaoang should have understood the danger of membership

in the Communist Party, due to the fact that, “since 1920, Congress has

maintained a standing admonition to aliens on the pain of deportation not to

becoming members of any organization that advocates the overthrow of the U.S.

by force and violence… [including] the Communist Party.” [70] He countered Caughlan’s claim that Mangaoang could not be deported because he was a national at the time of his involvement

in the Communist Party, citing a prior case that declared: “‘The fact that

petitioners… were made deportable after entry is immaterial. They are deported

for what they are now, not what they were.’” [71] This harsh assessment laid

out the essence of the government’s argument-- Mangaoang’s association with the Communist Party alone provided grounds for deportation and

essentially invalidated his rights as a national, or the work he was doing as

of present to fight for the rights of others. He cited yet another court case

to dismiss Mangaoang’s claim to the right of

expression and naturalization-- in America, Boyd argued, “‘the protection of

citizenship is open to those who qualify for its privileges.’” [72] Finally, Boyd dug in at

the racialized notion that Filipino’s were somehow undeserving of citizenship:

seen as non-white in the eyes of white citizens, non-citizens in the eyes of

the government, incapable of self-government because the Filipino race were “childlike,

‘Oriental’ savages.” [73] On June 17, 1953, John Caughlan and Ernesto Mangaoang were granted a rare victory in the 9th Circuit court, the apex of a

battle for belonging, political voice, and civil liberties for

Filipino-Americans that spanned nearly half a decade. Circuit Judge Walter

Pope, who once commented, “‘I find great satisfaction in the thought that generally speaking the courts are alert to

protect the rights of the most insignificant defendant…’” [74], delivered the opinion in

favor of Mangaoang. The victory effectively ensured

that deportation could not be used to remove non-citizen nationals under

statutes that granted Congress or other entities authority to deport "aliens". Allies Get Involved

Journey

to the Ninth Circuit Court

Battle

in the Court

The

Ruling

The Court was unable to declare with certainty that Mangaoang was both an alien and a Communist during 1938 and 1939, years that predated the finalizing of Philippine Independence in 1946. They presented a term that effectively surmises the legal and social intricacies of Filipino-Americans: “the Filipino non-United States-citizen-resident.” [76] Believing this case necessitated a strict constructionist viewpoint, the Court declared that Filipino-Americans should not be considered aliens under the “ordinary sense and connotation”, and therefore the language expunging aliens in the Act of 1917, 1918 or the McCarran Act.

There was, however, an aspect of Mangaoang’s situation that the Court was able to reach a resounding agreement on: deporting Mangaoang, a Philippine national, on the basis of legal statutes that completely ignored the complexity of his status, “would have a punitive impact.” [77] Judge Pope’s court acknowledged that the punishment of deportation, especially for a group that lacked representation in U.S. legal statutes, constituted severe punishment. Citing two cases as evidence, the court understood that “deportation can be the equivalent of banishment or exile” and that “…nothing can be more disingenuous than to say that deportation in these circumstances is not punishment.” [78] The dehumanizing categorization of Filipino-Americans as aliens enables the government to exclude and remove them from their home without considering the reduction of liberties to a mere afterthought.

Furthermore, the Court criticized the rashness-- or perhaps ignorance-- of the U.S. government in applying the McCarran Act to Filipino-Americans when there was “nothing to show that when Congress enacted [the Act], it had in mind the very special case of Filipinos…” [79] This highlighted the hypocrisies of a colonial United States that fought a bloody war to gain control of the Philippine Islands but refused citizenship, forcing the removal of Filipino-Americans with the attitude that they never belonged on American soil in the first place.

Outcome and Impact

Ernesto Mangaoang’s victory was celebrated with near immediacy by the groups that had supported him throughout his fight. The Lamp, the newspaper of the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born, celebrated the Mangaoang decision with a headline that read “Mangaoang Victory Holds Hope for Most Filipino-Americans.” The Washington State branch of the ACPFB and the Local 37 Union held a Victory Rally to celebrate “the victory of Ernie Mangaoang.” [80] In its report to members, the ACPFB declared that Mangaoang’s decision “[meant] that some 70,000 Filipino-Americans can no longer be intimidated by the Justice Department with the threat of deportation.” [81] They recognized that Filipino-Americans had gained a major victory in their right to political expression as current-- or former-- nationals. In a congratulatory letter to Ernesto Mangaoang, the ACPFB wrote of his case’s significance, that he “…made an outstanding contribution to the welfare of the American people.” [82] While the pain of ambiguous rights and identities was not healed with one decision, Mangaoang’s case created some clarity for Filipino-Americans throughout the U.S., and provided reassurance that they could not be forcibly removed as a result of changes in their legal status. The responses of the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born and the Local 37 union were a reminder of the remarkable support Mangaoang received, perhaps as a result of his own leadership and work, but further reflective of extraordinary organizations who were willing to take a stand against the government in the name of the people.

Myer C. Symonds, a Hawaii-based labor lawyer, excitedly penned a letter to Caughlan and Hesse a few days after the Mangaoang decision was announced. He was defending a Filipino-American client who was at risk of deportation when he learned of the Mangaoang decision. Upon informing the local U.S. attorney of the victory, the order for deportation was withdrawn. “In these days when it is so difficult to obtain a just decision in any case involving unions or political matters,” he wrote, “this decision is a great victory.” [83] The immediate legal impact of Mangaoang’s decision spread even further, as Abner Green, executive secretary of the ACPFB, informed Hesse that their victory “would clearly effect” 10,000 former citizens undergoing denaturalization cases as a result of their political affiliations. [84]

Caughlan released a memorandum where he declared Filipino-Americans who had come to the United States prior to Philippine Independence “immune from deportation.” [85] He noted, with some reservation, that the holding in the Mangaoang case “[was] not yet conclusively won,” as the Immigration Service announced it “[would] seek a writ of certiorari from the Supreme Court.” [86] Despite this, Caughlan encouraged, the importance of Mangaoang’s victory, “both to former (or present) nationals and former citizens is great.” 91 The Immigration and Naturalization Service’s appeal to the Supreme Court was denied on November 2, 1953, and Mangaoang’s legal victory for over 70,000 Filipino Americans was cemented into law.

Beyond its immediate impact, Mangaoang’s case set precedence and had substantial impact on legal procedure in the years that followed. It made it illegal to deport legal aliens without due process of law, including detention for lengthy periods before a hearing [87] and denial of bail without reason. [88] Although Mangaoang’s case was founded on the complex and unique experience of Filipino-American nationals in the early 1950s, the outcome of his case extended basic due process rights to all nationals and lawfully-admitted aliens within the U.S. Justice System.

Through his own self-determination and the rallying of groups like Local 7/Local37, the American Civil Liberties Union, and others, Mangaoang mounted a legal victory over the U.S. government for his own rights in the country he called home. While Ernesto Mangaoang’s story is not widely known, the fight for identity and belonging is widespread. His struggle reflects that of all U.S. nationals seeking to define and protect their fundamental rights. Mangaoang, like 70,000 Filipino Americans, was effectively an American by birthright. This fight, however, does not end in 1953 with Mangaoang’s story. The imperialistic past of the United States is still evident today, most notably in Puerto Rico, an unincorporated U.S. territory. Considered American citizens on paper, the 3.2 million people living in Puerto Rico lack the right to vote in U.S. elections, and their representative in Congress is a non-voting member. The U.S. federal government limits aid and the territory is more economically disenfranchised than any of the fifty states. [89] To this day, the United States continues to impose imperialistic control over peoples, circumventing their rights explicitly, and more subtly, depriving them of first-class citizenship by othering them in political rhetoric and attitudes. The fight of Americans -- nationals, naturalized and by birth -- to be granted full rights of a citizen continues. The fight for the right to be.

© Copyright Noelle Morrison 2020

HSTAA 498 Autumn 2019

[1] Mangaoang, Ernesto A. “Filipinos Want Equal Rights or Independence.” The Oregonian, September

21, 1931.

[2] “Union Leader Arrested.” The Seattle Daily Times, August 1, 1949, 1.

[3] Mangaoang v. Boyd, 186 F.2d 191 (9th Cir. 1950).

[4] “New Move to Free Two Red-Suspects.” The Seattle Daily Times, November 15, 1950, 8.

[5] Baron, Patricia. n.d. A Brief History of the Republic of the Philippines. Accessed December 1, 2019. http://www.mtholyoke.edu/~baron22p/classweb/briefhistory.html.

[6]Schlimgen, Veta R. 2010. “‘Neither Citizens nor Aliens: Filipino “American Nationals” in the U.S. Empire, 1900–1946.’” University of Oregon, 93.

[7] Schlimgen, Veta R. 2010. “‘Neither Citizens nor Aliens: Filipino “American Nationals” in the U.S. Empire, 1900–1946.’” University of Oregon, 93.

[8] Toyota v. United States, 268 U.S. 402, 45 S. Ct. 563, 69 L. Ed. 1016 (1925).

[9] Fujita-Rony, Dorothy B. 2003. American Workers, Colonial Power: Philippine Seattle and the Transpacific West, 1919-1941. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

[10] U.S. Congress, 1934. "Recognition of Philippine Independence and Withdrawal of American Sovereignty." 73rd Congress, Session II, March 24.

[11] Gancy, B. M. 1937. "Memorandum presented to the American Federation of Labor." Filipino League for Social Justice, November 2.

[12] Gancy, B. M. 1937. "Memorandum presented to the American Federation of Labor." Filipino League for Social Justice, November 2.

[13] Internal Security Act of 1950, Public Law 81-831 [H.R. 9490], (1950).

[14] Chang, Hosoon. "The First Amendment During the Cold War: Newspaper Reaction to the Trial of the Communist Party Leaders under the Smith Act." Free Speech Yearbook 31, no. 1 (1993): 66.

[15] Mangaoang, B.J., interview by Daren Salter and James N. Gregory. 2006, Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project

[16] Zaragosa, Vargas. 2005. "Labor Rights Are Civil Rights: Mexican American Workers in Twentieth-Century America." Princeton University Press p. 154.

[17] Ellison, Micah. 2005. "The Local 7 / Local 37 Story Filipino American Cannery Unionism in Seattle, 1940-1959." The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project; “Ernesto Mangaoang discusses the Alaska Cannery Workers lockout.” Tyler, Jerry, “Reports from Labor” broadcast. May 11, 1950.

[18] Immigration Act of 1918. 1918. H.R. 12402 (65th Congress. Session II, 16 October).

[19] Ellison, Micah. 2005. "The Local 7 / Local 37 Story Filipino American Cannery Unionism in Seattle, 1940-1959." The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

[20] Caughlan, John. Letter from John Caughlan to John Boyd. John Caughlan Papers, Box 26, Fld. 3. UW Libraries Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[21] Caughlan, John. Letter from John Caughlan to John Boyd. John Caughlan Papers, Box 26, Fld. 3. UW Libraries Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[22] “Habeas Corpus Action Begun.” The Seattle Daily Times, November 22, 1949, 8.

[23] "11 Arrested As U.S. Opens Drive on Reds." The Seattle Daily Times, October 23, 1950, 1.

[24] "Bowen Refuses to Free Aliens Arrested Here." The Seattle Daily Times, November 1, 1950, 10.

[25] "2 Aliens Win Freedom, Will Be Rearrested." The Seattle Daily Times, October 27, 1950, 27.

[26] “Hearing Set For 2 Aliens.” The Seattle Daily Times, October 28, 1950, 5.

[27] "Bowen Refuses to Free Aliens Arrested Here." The Seattle Daily Times, November 1, 1950, 10.

[28] “New Move to Free Two Red-Suspects.” The Seattle Daily Times, November 15, 1950, 8.

[29] “Bowen Denies Writ Freeing Mangaoang.” The Seattle Daily Times December 8, 1950, 50.

[30] Caughlan, John. Letter from John Caughlan to John Boyd. John Caughlan Papers, Box 26, Fld. 3. UW Libraries Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[31] Letter from Ernesto Mangaoang to Bill Gettings. January 15, 1952. John Caughlan Papers, Box 26, Fld. 3, University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[32] Soll, George. "Letter from George Soll to Max Nicolai.", December 12, 1950. Princeton, New Jersey: American Civil Liberties Union Papers, 1912-1990. TS Years of Expansion, 1950-1990 Box 825, Folder 36, Item 337. Mudd Library, Princeton University.

[33] Karen Mason, Kathryn E. Stallard, and Eric Uhl. 2011. American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born Records (1926-1980s). Accessed December 1, 2019. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/s/sclead/umich-scl-acpfb?view=text#Summary%20Information.

[34] Senate of the California State Legislature. 1948. "Fourth Report - Un-American Activities in California - 1948: Communist Front Organizations."

[35] Committee on Un-American Activities, House. 1957. "Communist Political Subversion. Part 2: Appendix: Exhibit No. 618: Northwest Conference to Fight Deportation." 84th Congress, 2nd Session.

[36] Committee on Un-American Activities, House. 1957. "Communist Political Subversion. Part 2: Appendix: Exhibit No. 618: Northwest Conference to Fight Deportation." 84th Congress, 2nd Session.

[37] Green, Abner, July 3, 1953. Letter from Abner Green to Siegfried Hesse, John Caughlan Papers (UW Libraries Special Collections) Box 27, Fld. 3.

[38] “Deportation of Mangaoang.” The Seattle Daily Times, August 9, 1951, 10.

[39] Caughlan, John. Letter from John Caughlan to Richard Gladstein. January 29, 1952. John Caughlan Papers, Box 27, Fld 2. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[40] “Mangaoang Loses Round in Court Battle.” The Seattle Daily Times, August 17, 1951, 38.

[41] Internal Security Act of 1950, Public Law 81-831 [H.R. 9490], (1950).

[42] Caughlan, John. Letter from John Caughlan to Richard Gladstein. January 29, 1952. John Caughlan Papers, Box 27, Fld 2. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[43] Caughlan, John. Letter from John Caughlan to Richard Gladstein. January 29, 1952. John Caughlan Papers, Box 27, Fld 2. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections, Seattle, WA.

[44] “Board Upholds Deportation of Mangaoang.” The Seattle Daily Times, December 26, 1951.

[45] “Mangaoang to Appeal Against Deportation.” The Seattle Daily Times, December 27, 1951, 30.

[46] “Mangaoang to Appeal Against Deportation.” The Seattle Daily Times, December 27, 1951, 30.

[47] “Mangaoang’s Hearing Continued.” The Seattle Daily Times, January 2, 1952, 3.

[48] “2 Filipinos Lost Round in Court Fight.” The Seattle Daily Times, April 14, 1952, 8.

[49] “Deportation Fight Lost by Mangaoang.” The Seattle Daily Times, May 21, 1952, 21.

[50] “2 Filipinos Lost Round in Court Fight.” The Seattle Daily Times, April 14, 1952, 8.

[51] Letter from John Caughlan to Jeff Kibre, William Gettings, and Ernesto Mangaoang. June 4, 1952. John Caughlan Papers, Box 25, Fld. 5. University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle WA.

[52] Letter from John Caughlan to Jeff Kibre, William Gettings, and Ernesto Mangaoang. June 4, 1952. John Caughlan Papers, Box 25, Fld. 5. University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle WA.

[53] Letter from John Caughlan to Jeff Kibre, William Gettings, and Ernesto Mangaoang. June 4, 1952. John Caughlan Papers, Box 25, Fld. 5. University of Washington Special Collections, Seattle WA.

[54] “Mangaoang Files Appeal to Circuit Court.” The Seattle Daily Times, July 18, 1952, 19.

[55] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Concise Abstract of the Case, 4.

[56] Bolstad, Erica. “Oregon funds program to help immigrants with legal aid.” The Oregonian, November 23, 2019.

[57] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Specification of Errors, 7-9.

[58] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Specification of Errors, 7-9.

[59] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellant’s Summary of Argument, 11.

[60] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellant’s Summary of Argument, 9.

[61] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellant’s Summary of Argument, 9.

[62] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Summary of Argument, 10.

[63] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellant’s Argument, Point 1, 14.

[64] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellant’s Argument, Point 1, 13.

[65] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellant’s Argument, Point 1, 15.

[66] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellant’s Argument, Point 1, 16.

[67] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellee’s Argument, 5.

[68] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellee’s Argument, Point 2, 10.

[69] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Appellee’s Argument, Point 2, 15.

[70] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Argument in Answer to Appellant, 21.

[71] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Argument in Answer to Appellant, 22.

[72] Mangaoang v. Boyd, No. 13537. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Argument in Answer to Appellant, 22.

[73] Carl Schurz, "Thoughts on American Imperialism," Century Illustrated Magazine, vol. 56, no. 5 (September 1898), 781-88, and "Carl Schurz Speaks to Anti-Imperialists" New York Times, 29 September 1900, 3; "Senator Beveridge On the Philippines," New York Times, 10 January 1900, 5.

[74] Browning, James R. 2019. "Remarks at the Dedication of Walter Lyndon Pope Memorial Library." Montana Law Review 80 (2): 352.

[75] Schlimgen, Veta R. 2010. ""Neither Citizens nor Aliens: Filipino “American Nationals” in the U.S. Empire, 1900–1946." University of Oregon, 440-441.

[76] Mangaoang v. Boyd, 186 F.2d 191 (9th Cir. 1950).

[77] Mangaoang v. Boyd, 186 F.2d 191 (9th Cir. 1950).

[78] Mangaoang v. Boyd, 186 F.2d 191 (9th Cir. 1950).

[79] Mangaoang v. Boyd, 186 F.2d 191 (9th Cir. 1950).

[80] “Mangaoang Victory Holds Hope for Most Filipino-Americans.” The Lamp, June-August 1953, No. 78, p. 2

[81] Committee on Un-American Activities, House. 1957. "Communist Political Subversion. Exhibit V: Report - 10” 84th Congress, 2nd Session, 8365.

[82] Committee on Un-American Activities, House. 1957. "Communist Political Subversion. Exhibit V: Resolutions - 11” 84th Congress, 2nd Session, 8355.

[83] Symonds, Myer C. Letter from Myer C. Symonds to John Caughlan and Siegfried Hesse. John Caughlan papers, Box 27, Fld. 3. University of Washington Special Collections.

[84] Green, Abner, July 3, 1953. Letter from Abner Green to Siegfried Hesse, John Caughlan Papers (UW Libraries Special Collections) Box 27, Fld. 3.

[85] Caughlan, John “Memorandum: Mangaoang v. Boyd,” John Caughlan Papers, Box 26, Fld. 7, 2. University of Washington Special Collections.

[86] Caughlan, John “Memorandum: Mangaoang v. Boyd,” John Caughlan Papers, Box 26, Fld. 7, 2. University of Washington Special Collections.

[87] Kansas, Sidney. Immigration and nationality act, annotated, with rules and regulations. New York, Immigration Publications, 1953-1959, 135.

[88] Kansas, Sidney. Immigration and nationality act, annotated, with rules and regulations. New York, Immigration Publications, 1953-1959, 171.

[89] Campbell, Alexia. 2019. Vox News. July 30. Accessed November 19, 2019. https://www.vox.com/2019/7/30/20728083/puerto-rico-statehood-political-crisis-governor.