Land development companies were responsible for most but not all of the racial restrictive covenants in Seattle. In some areas, homeowners themselves organized campaigns to restrict their own properties. This was most common in the older areas of the city that had been developed before the 1920s. Much of Seattle had already been plotted and developed before the era of racial covenants. In those neighborhoods, homeowners’ associations and homeowners themselves engaged in a more complicated process of establishing deed restrictions.

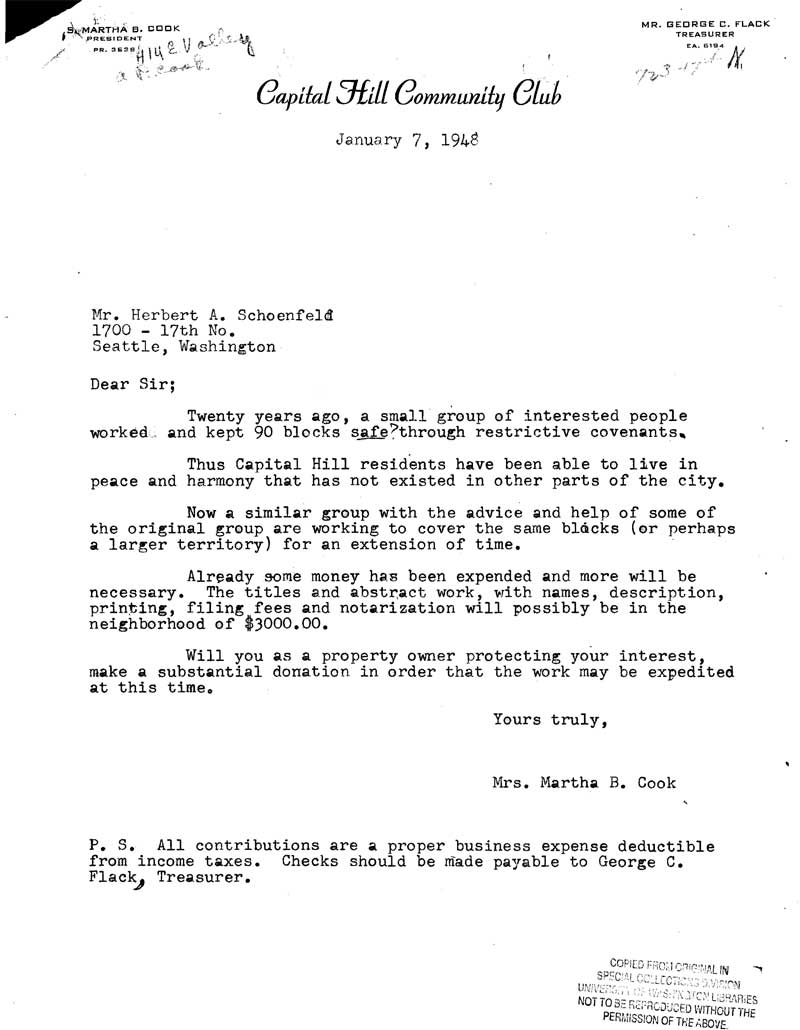

The best example of this occurred in Capitol Hill. Worried that African American families might seek housing north of Madison Ave, a group of white homeowners in the upscale neighborhood of Capitol Hill began a campaign in 1927 to change all of the deeds in the area. This was a more complicated undertaking than adding a restriction to newly subdivided property. An extensive effort was required to convince the hundreds of homeowners to sign on to the restrictive covenant that would bind their property and limit their freedom and that of future owners. Just who led the campaign is not clear, but it seems to have been associated with the Capitol Hill Community Club. In a letter written 20 years later, Martha B. Cook, a club leader, stated that “a small group of interested people worked and kept 90 blocks [of Capitol Hill] safe through racial restrictions.”23 She went on to extol the “mutual benefits, protection, preservation and promotion of the value of that land and properties” achieved through the covenant campaign. According to Katherine Pankey, a University of Washington student who researched the Capitol Hill covenants in 1947, the campaign yielded 38 neighborhood restrictive agreements "involving 964 home owners, 183 blocks, and 958 lots."24

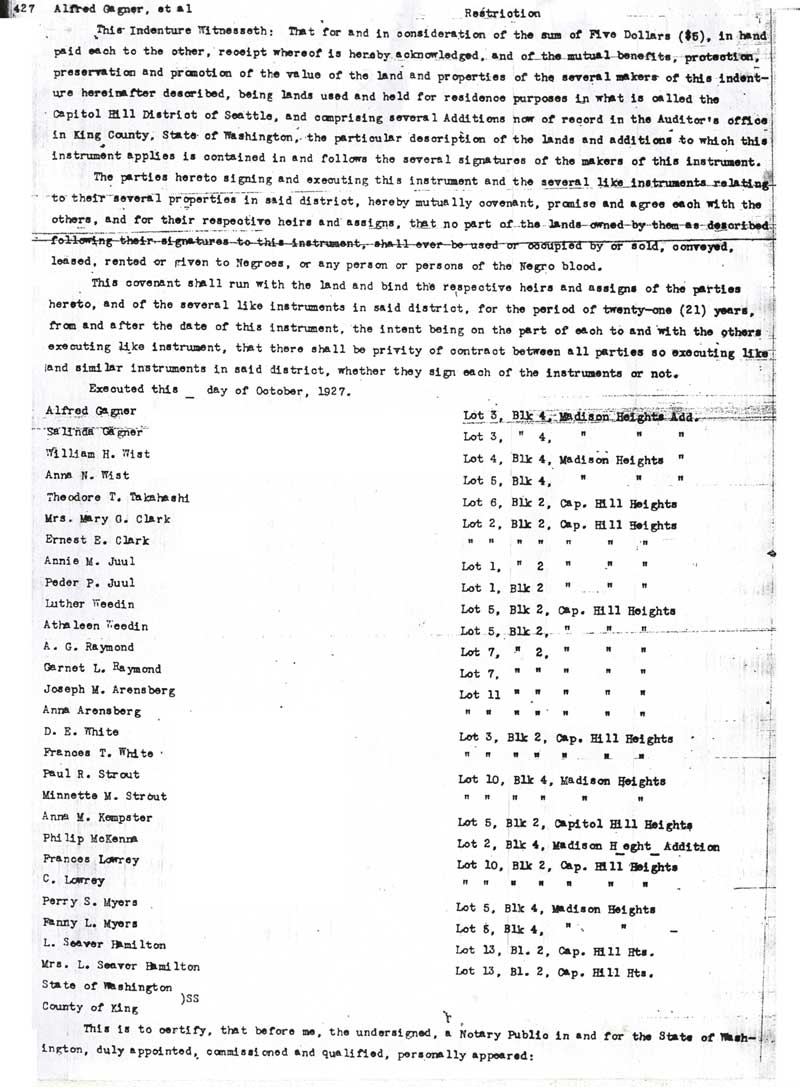

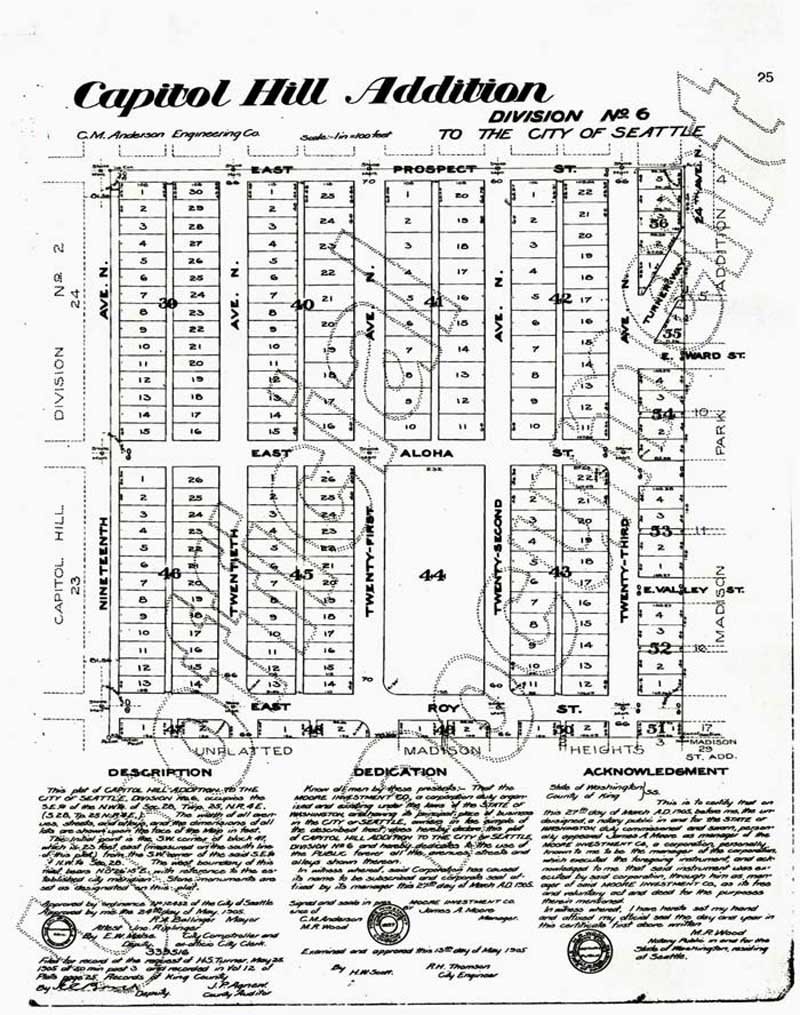

The campaign lasted more than three years as organizers persuaded block after block of white property owners to sign the agreement in the presence of a notary. The first of the covenants was filed with the County Recorder on October 10, 1927. It covered the twenty properties in the block surrounded by 21st and 22nd Ave N between Aloha and Prospect. E.A and Lillian Goetz were listed first among the nineteen property owners, mostly couples, who signed. 25 Targeting African-Americans but not mentioning Asian Americans, its wording was shared by most of the Capitol Hill covenants:

“The parties hereto signing and executing this instrument and the several like instruments relating to their several properties in said district, hereby mutually covenant, promise and agree each with the other, and for their respective heirs and assigns, that no part of the lands owned by them as described following their signatures to this instrument, shall ever be used or occupied by or sold, conveyed, leased, rented or given to Negroes, or any person or persons of the Negro blood.”26

Interestingly, the Capitol Hill covenants specified that they would expire in 21 years. This was in contrast to the restrictions placed on plat maps and deeds by land developers which were intended to be enforced in perpetuity. This expiration date came into play during the campaign to stop the use of racial restrictive covenants.

Seattle’s African American, Jewish, and Asian American residents resented and resisted racial restrictive covenants from the very beginning, and over the years had managed to disrupt some efforts to lock up neighborhoods. As detailed in "Racial Restrictive Covenants History: Enforcing Neighborhood Segregation in Seattle" resistance became more effective after World War II as new civil rights organizations like the mixed race Christian Friends of Racial Equality (CFRE) joined the cause.

One victory came in 1946, when an attempt by White residents of the Rainier District to impose restrictive covenants was blocked by a campaign coordinated CFRE. Two years later an expanded coalition defeated the attempt by the Capitol Hill Community Club to renew the covenants covering nearly 1000 homes in Capitol Hill.

With the restrictions due to expire in 1948, the Community Club petitioned for area residents to renew their covenants in order to ensure the continued “protection” of the neighborhood. Furthermore, the neighborhood association wanted to extend the restrictions to cover additional blocks. In order to add the new areas or renew the existing covenants, new documents needed to be notarized and filed with the city. The Community Club began the campaign by asking for donations from community members to raise $3,000 to cover this cost.46

In response to this move on the part of the Community Club, the Civic Unity Committee (CUC), in alliance with the CFRE and NAACP, attempted to convince area residents not to extend their covenants.47 As part of this campaign, CUC published an informational booklet that answered questions on the scope and definition of racial restrictive covenants.48 This booklet maintained that having a non-White neighbor was not detrimental to either the quality of the neighborhood or to the real estate value of homes: “White people are apt to associate ill kept and unsightly neighborhoods with Negroes,” with the result that when a black family moves nearby, “white people may offer their property for sale at less than it is worth and move out with almost panic speed.”49 The CUC was compelled to mention this fact in their informational booklet because real estate devaluation was one of the most widely cited reasons for upholding racial segregation in Seattle. This publication was thus an attempt to educate Whites about the faulty logic behind certain prejudices, in order to persuade them to change their mind about the necessity for racial restrictive covenants.

Along with the pamphlet, the CUC sent letters to area residents, urging them not to sign the petition to renew the covenants. One Capitol Hill resident, a jewelry dealer named Harry Druxman, thoughtfully responded by stating that he could not “be party to deprive any one of their rights,” and as such had already declined to sign the petition prior to receiving the letter from the CUC.50 Harry Druxman’s response illustrates that some Whites by 1948 opposed racial segregation in Seattle. CUC’s letter campaign was a success, as not one of the Capitol Hill covenants was extended in 1948. The fact that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that summer that covenants would no longer have the force of law probably helped the CUC campaign.

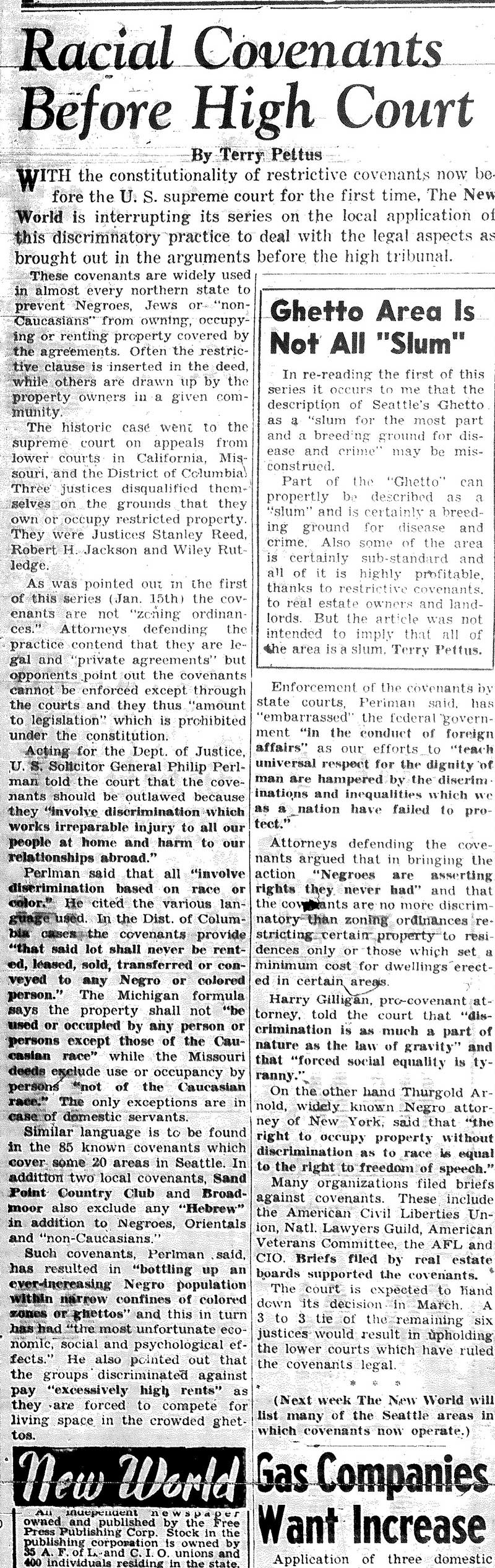

Also joining the campaign against covenants in 1948 was The New World, a weekly Seattle-based Communist newspaper, which ran a series of articles exposing the effects of restrictive covenants. The first article, by editor Terry Pettus, plainly states that “citizens of Negro and Oriental ancestry, and (in some cases) Jews are prevented from buying or renting the homes of their choice,” due to restrictive covenants.51 No similar articles have yet been found in any of Seattle’s major newspapers. This newspaper, therefore, provided readers with information that had not been widely circulated.

The New World attributed much of the factual information on covenants to the research accomplished by University of Washington student Katharine Pankey. For an Anthropology assignment, Pankey cataloged “eighty-five covenants for twenty different districts,” especially those covering the Capitol Hill neighborhood. She concluded by stating, “even though a non-White person surmounts the formidable barriers of economic inequalities, he still is not permitted to live where he might on the basis of his choice and the availability of homes.”54 This statement, and Pankey’s work in general, provided a candid portrayal of the experiences of non-Whites in an era when most Whites were still blissfully ignorant of the profound effects of racial restrictions.

Copyright © Catherine Silva 2009, HSTAA 498 Autumn 2008

23 Letter written by Martha B. Cook of the Capitol Hill Community Club, CUC Collection, 7 January 1948.

24 Katharine I. Grant Pankey, “Restrictive Covenants in Seattle: A Case Study in Race Relations.”

25 There may have been earlier petitions. This is the earliest date of those in the database. Covenant for Block 41, Capitol Hill addition to Seattle, District No. 6. Notarized by J. L. Fitzpatrick on 10 October 1927. In the possession of Professor James Gregory and the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

26 Ibid.

46 Letter written by Martha B. Cook of the Capitol Hill Community Club, CUC Collection, 7 January 1948

47 Heather MacIntosh, “Civic Unity Committee in Seattle,” HistoryLink,//www.historylink.org accessed 8 December 2008.

48 Pankey, “Restrictive Covenants in Seattle: A Case Study in Race Relations.”

49 Ibid.

50 Letter from to the Civic Unity Committee from Harry Druxman, CUC Collection, 1 May 1948.

51 Terry Pettus, “Seattle is Blighted by Restrictive Covenants,” _The New World, _15 January 1948.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

54 Pankey, “Restrictive Covenants in Seattle: A Case Study in Race relations.”