In the early 1930s, Joseph Staton, an employee of _The_ _Northwest Enterprise,_ a prominent African-American newspaper in Seattle, was arrested and booked in jail for vandalizing an automobile parked on the corner of 3rd and Yesler in Pioneer Square. In court a few days later, the judge requested to see a section of a spare tire cover that Staton had removed. When the court attendants brought it out, the judge laughed and remarked, “Well, I’ll just fine you three dollars and you go on home.”1

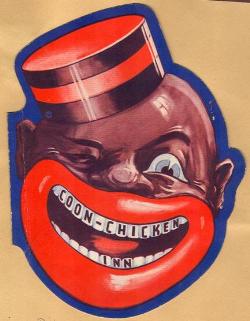

The image that Staton removed from the spare tire cover featured the logo of the Coon Chicken Inn, a fried chicken restaurant chain in the Northwest whose logo featured a ‘Coon’, or a racist caricature of an African-American male popular in 19th century minstrel theatre and early 20th century advertising. The Coon Chicken Inn’s ‘Coon’ wore a Porter’s uniform; its face featured a winking left eye and enlarged red lips forever gaping to expose the words ‘Coon Chicken Inn’ etched on the top row of its shining white teeth.

To fully comprehend the significance of the CCI logo, it is important to step back and examine the history of the ‘Coon’ caricature itself. The term _coon_ emerged in early America as a shortening of _raccoon_ and, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, soon became synonymous with “a sly, knowing fellow,” and, subsequently, “a Negro.”2 Though originally associated with white ‘backcountry folk’, the shift in the use of _coon_ from an expression describing a country rube to a derogatory term for an African-American is connected to the introduction and instant success of the 19th century minstrel show character Zip Coon.3

Though not the first blackface character in the minstrel tradition, according to cultural critic John Strausbaugh, Zip Coon became the first popular minstrel personality to represent the “black urban dandy… a ‘negar’ who ‘acts white.”4. For whites who feared job competition once slavery ended, the Zip character served as a symbol of “the terror that lower-class whites had of being left at the bottom if ‘niggars’ like Zip got too uppity.”5. On stage, Zip Coon would act like a braggart and a fool, eliciting laughter and fascination while reinforcing white supremacy and hostility toward African-Americans.

In the late 19th century, the Coon caricature was revised to fit the predilections of post-Civil War whites who, according to historian Kenneth Goings, were not prepared to “handle the status of African-Americans as free and technically equal.”6 The Coon caricature became a way for both northerners and southerners to relive a nostalgic memory of the Old South, one where black slaves were cared for by benevolent white masters and in which African-American males loved to sing, dance, and steal chickens. The origin of this chicken-thieving stereotype is unclear, but is likely rooted in 18th and 19th century narratives and images and in the fact that slaves often did steal chickens and livestock from masters as a form of protest or to augment their meager food rations.78 After emancipation, the inclusion of such stereotypes and caricatures of African-Americans in collectibles and advertising became an effective way for whites to reinforce the myth of the Old South in the collective national memory.

The representation of blacks as servile dependents flourished in American advertising and in the ‘trinket market’ of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Aunt Jemima, the character behind the ready-made pancake, was sold to a receptive American market in 1889 and with her came a proliferation of advertisements and collectables featuring the Mammy, the simple, ever-faithful slave woman who cooked, supervised other house slaves, watched the children, and completed countless additional tasks. ‘Uncle Tom’, originally a character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, became another popular stereotype who, like Mammy, submissively and contentedly served the ‘massa’. Sambo, Jim Crow, Pickaninny, and Jezebel are further examples of black stereotypes used to sell anything from soap to tobacco and who appeared as objects as diverse as rag dolls and salt and pepper shakers. And of course, the Coon remained an ever-popular stereotype prominent throughout the United States. Coon Cards, or minstrel-themed postcards, became an established form of communication with captions like “The Evolution of a Coon,” “Golly, see dem chickens fly! Dey know a nigger’s goin’ by” and “A Home Run with a Chicken in His Pants.”9 Like the minstrel shows, these cards depicted blacks with “exaggerated and animal-like features … thick lips, kinky hair, flat noses, big ears, and big feet.”10

The fact that the Coon Chicken Inn opened its doors one hundred years after Zip Coon first danced across the stage to the delight of white working-class audiences serves not only as a testament to the power of the Coon image, but also to enduring racial tensions in the Pacific Northwest in the early 20th century. The restaurant was founded in Utah in 1925 by Maxon Lester Graham. According to a brief historical account written by Graham’s grandson and published on the website of Ferris State University’s Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Lester Graham and his wife Adelaide got into the fried chicken business after spending many Sundays driving to a small town south of Salt Lake City to eat at a restaurant that served “excellent chicken.” Deciding that fried chicken would do well in suburbia, they built a small restaurant in the Salt Lake suburb of Sugar House. The business immediately gained popularity. However, in July of 1927, the restaurant caught fire and burnt to the ground. In a large publicity stunt, Graham rebuilt the Coon Chicken Inn in 10 days. Four years later, two additional roadside Coon Chicken Inns opened in Portland and Seattle and a fourth branch would eventually open in Spokane, Washington.11The massive Coon head served as the entryway to all four of the restaurants. The chain flourished for nearly two decades until Graham closed the branches in the late 1940s. Though Graham never revealed what inspired him to use the Coon caricature as the gimmick for his fried chicken restaurant, the prevalent stereotype of African-Americans as chicken lovers proved to be identifiable and marketable enough to attract white consumers who saw the image as comedic, not cruel. The name connected African-Americans and their ‘favorite dish,’ implicitly signifying that the chicken was authentic and high quality, even for the ‘Coon’.

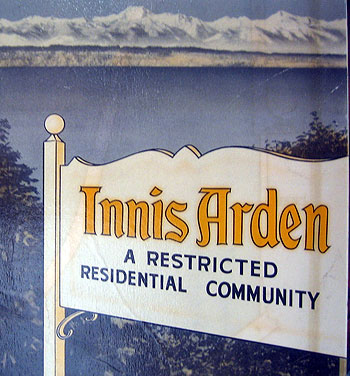

In Seattle, the twelve-foot grinning Coon head erected in plain view of the increasingly active Bothell Highway served as a reminder of racial segregation in the city and the surrounding area. The 20th century migration of blacks to the Northwest left many white Seattleites wary of the changing racial landscape of the city. Racial restrictive covenants – housing restrictions that prevented nonwhites from buying or renting homes in most Seattle neighborhoods – took root in the 1920s as a reaction to this black migration. For example, a Lake City covenant covering property near the Bothell Highway from 1930 reads:

“Said lot or lots shall not be sold, conveyed, or rented nor leased, in whole or in part, to any person not of the White race; nor shall any person not of the White race be permitted to occupy any portion of said lot or lots or of any building thereon, except a domestic servant actually employed by a White occupant of such building.”12

Consequently, by 1930 the majority of African-Americans were concentrated in the area later known as the Central District—located 8 miles from the Coon Chicken Inn.

Though Lake City remained outside of the Seattle city limits until 1954, the Old Bothell Highway played a role in setting Seattle’s racial landscape from the early 20th century. The area gained township status in 1949 after a flood of families flocked to the suburbs after World War II. Lake City’s development was always dependent on the automobile; in 1911, King County improved the Bothell Highway, an old logging road, by paving it with Warrenite. An unincorporated area of King County easily accessible by automobile, the Old Bothell Highway proved to be a prime location for roadside restaurants. As early as 1919, southern and minstrel-themed fried chicken restaurants were attracting Seattleites who, according to Hattie Graham Horrocks’ guide to Seattle restaurants, “wished to drive out-of-town for the occasional dinner.” My Southern Inn, renown for “frying chicken in the window in plain sight of passersby,” became one of the first, soon followed in 1921 by Bob’s Place and in 1923 by Mammy’s Shack.13 Though historian John A. Jakle argues that most roadside restaurants facades were “quite utilitarian,” a few, like the CCI, embraced a more fanciful, programmatic architectural design. Like the landmark Brown Derby restaurant in Los Angeles or the Teapot Dome Service Station in Zillah, Washington, programmatic, or novelty architecture aimed to “arrest the attention of the speeding public” by erecting unconventional structures.

Once situated on the Old Bothell Highway, Lester Graham vigorously promoted the new restaurant. On August 31st, 1930, an advertisement for the CCI took up almost a full page in the Seattle Times.15 Under the heading Coon Chicken Inn Opened in Seattle, the page featured the short columns, “Coon Chicken? Ask Anyone Who Came From South,” which defined ‘coon’ chicken as “the way the fowl is cooked by the real, old-fashioned Mammy;” “Highway Resort is One of Huge National Chain” (though at this time only the Salt Lake location existed); “Inn is Built From Local Materials;” “Utah Folk are Champions of Fried Chicken;” “Telephone Will Bring Chicken to Your Home;” and “Parking Space is Provided at Inn for 500 Autos.” The page also included a large advertisement for the CCI, complete with this description of the restaurant:

“The best fried chicken you ever tasted! That’s a mighty strong statement, but you’ll agree after visiting Seattle’s newest, most unique eating place that it’s a mighty true one. Coon Chicken Inn brings to Seattle and the Northwest a nationally-famous method of cookery, and provides a novel, pleasing restaurant at which you’ll enjoy eating. Good food served in a cheerful atmosphere! A service that will fit in with your every plan—party, after-theatre affair, or the wish for a splendid meal! Throughout America our splendid foods have pleased the most discriminating palates. Coon Chicken Inn is not ‘just another restaurant’—it is an innovation providing a pleasurable change from the ordinary café—a new eating place whose cuisine is considered in a class by itself, head and shoulders above the average.”

The advertisement makes no mention of African Americans, a conspicuous silence considering the restaurants logo and architecture and one that speaks to just how uncontroversial the Coon image was for most Seattleites. Of course, for African Americans, the imagery was enough to announce the North End’s hostility towards blacks and let all races know who was and who was not welcome. A photograph of the newly opened CCI building displayed the gaping-mouthed Coon-head entrance with its large red lips, winking eye, and porter’s hat sitting atop a bald, black head. On August 31st, _The Seattle Times_ provided the publicity the restaurant needed to show off its “uniqueness” to all Seattle—black and white communities alike. Though the edifice of the CCI stood in North Seattle, the image of the Coon manifested itself in places beyond the restrictive covenant lines; it infiltrated areas of Seattle where the Coon image did not resonate with citizens.

Though the black population was predominantly restricted to the Central District area, the CCI paraded its logo on public and portable spaces, inundating African-Americans with the offensive Coon caricature. _The Seattle Times_ ad was just one form of invasive advertising employed by the CCI. Another form manifested itself any time a customer ordered chicken for delivery. Orders were filled by a deliveryman driving the ‘Coon Car’, which brought “piping hot, crisp, delicious” chicken to “any part of the city—and right quickly too.” Plastered with the CCI logo, the ‘Coon Car’ allowed the racist imagery to infiltrate “any part of the city” from “10 o’clock in the morning till 2 o’clock the next.”16

But the most racially charged form of advertising lay in the spare tire cover. In the early years of the CCI, Graham ordered more than 1,000 automobile spare tire covers that prominently featured the restaurant’s Coon logo.17 Consumers placed the covers over the spare tire on the back of their vehicles. In displaying these covers, the consumer advertised the CCI and implicitly claimed an affinity with the blatant racial hostility and fear that the image represented.

Though the CCI advertisements served up a continual reminder of the place of black people in Seattle’s racial landscape, African-Americans did not take this exhibition of racial hostility lying down. Like reactions to other “little nasties,” which historian Quintard Taylor identifies as the casually bigoted behavior that typified racism in Seattle, black Seattleites objected vigorously. During the early years of the CCI, African-Americans protested on both individual and community levels, employing remarkable vigilance and determination to fight back against the grossly offensive Coon image.18

Joseph Staton was among those who took individual action against the CCI on a small-scale. In an oral history interview recorded by Ester Mumford in 1975, Staton relayed the story of his arrest in the 1930s for slicing the Coon image out of a CCI spare tire cover. Staton and four friends created what Staton referred to as a “contest”: each friend put in 50 cents and whomever cut the most Coon faces out of tire covers after thirty days would win the pot. W. H. Wilson, the editor of the _Northwest_ _Enterprise_ and Staton’s employer, would lend Staton his automobile for work; one day while borrowing Wilson’s car and driving downtown with his friends, Staton watched one of his friends hop out of the car and cut out the Coon logo on a CCI tire cover as part of the contest. The automobile owner noted the license of Wilson’s car and the police traced the prank back to Joseph Staton, who was subsequently arrested, booked, and fined the three dollars.19

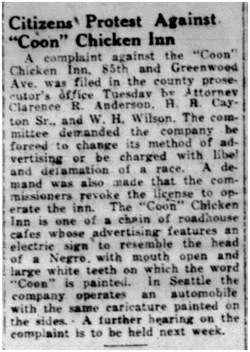

In an another act of protest, The NAACP and _The Northwest Enterprise_ teamed up in a two-year battle with Lester Graham over the CCI’s Coon logo. The first sign of the battle appeared in a column posted in the _Enterprise_ on September 18, 1930—not a month after Seattleites were greeted by the picture of the Coon inThe Seattle Times. The article, headlined “Citizens Protest Against ‘Coon’ Chicken Inn,” informed the predominantly African-American readership that Clarence R. Anderson, a black attorney, William H. Wilson, the editor of the _Northwest Enterprise_ and president of the Seattle NAACP, and Horace R. Cayton, an NAACP member and long-standing civil rights advocate, collectively filed a complaint against the CCI over its advertising. The three activists demanded that the company change its method of advertising “or be charged with libel and defamation of a race.”20 Similar to a 1930 lawsuit filed by the Seattle NAACP against the local packaging plant, Fresh Products Inc., whose peanut product, ‘Three Little Niggers’, displayed “three colored children standing in a peanut shell,”21 the NAACP/_NW Enterprise_ protest against the CCI took shape in an impressive legal framework that boldly challenged the derogatory representation of blacks in advertising. A follow up column in the _Enterprise_ on September 25th claimed victory on the side of the protesters. It stated that Graham agreed to change the style of advertising by removing the word ‘Coon’ from the ‘Coon Car’, repainting the front of the CCI, and canceling an order of the 1,000 automobile tire covers.22

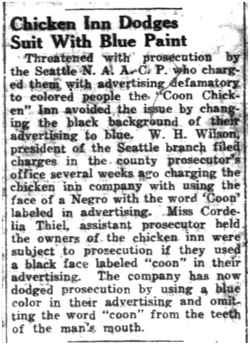

It proved a somewhat hollow victory, however. In 1931 _The NW Enterprise_ reported on a protest filed by W. H. Wilson against the CCI for violating its previous agreement to “discontinue the distribution of offensive tire covers.” Despite this, the column did note a success: the repainting of the CCI door logo from black to red.23This small stride, however, was not enough to fully erase the image of the Coon from Seattle. Not only did Graham claim the restaurant name to be copyrighted and therefore unchangeable, he managed to evade the lawsuit altogether by merely changing the color of the Coon logo. The final column in the _NW Enterprise_ reads as follows:

“Chicken Inn Dodges Suit with Blue Paint: Threatened with prosecution by the Seattle NAACP who charged them with advertising defamatory to colored people the ‘CCI’ is avoiding the charge by changing the black background of their advertising to blue… Miss Codetis Thiel, assistant prosecutor held the owners of the chicken inn were subject to prosecution if they used a black face labeled ‘coon’ in their advertising. The Company has now dodged prosecution by using a blue color in their advertising and [removing] the word ‘coon’ from the teeth of the man’s mouth”24

Although their campaigns were unsuccessful, both Joseph Staton’s ‘contest’ and the NAACP/_NW Enterprise_’s joint protest against the CCI are impressive demonstrations of black agency in Seattle, and they garnered some support from white authorities. The African-American population, while still only .9 percent of Seattle’s population in 1930 and 1 percent in 1940, established itself as a fighting force for equality in the first half of the century.25Nevertheless, regardless of the battles waged by the black community, the racial hostility of whites in Seattle reigned throughout the 1930s, keeping the image of the Coon alive and the CCI in business.

It is interesting to note that the CCI opened its doors in the midst of the Great Depression, yet the restaurant not only endured throughout the Depression’s worst years—it thrived. Whites did not seem to find the Coon logo problematic in the least. Indeed, while overt hostility toward African-Americans was not uncommon, the dominant attitude of white Seattleites toward evidence of racism and campaigns for equality was simply apathy. In this way, the Coon Chicken Inn served as a beacon of white bigotry in the North End and tapped deep into the race and class-consciousness of Seattleites, bringing to light the reality of white and black relations of the day.

On the Old Bothell Highway, the Coon-head gimmick certainly managed to attract the attention of passersby, but the question arises of who actually frequented the restaurant. In looking back at the _Seattle Times’_ August 1930 advertisement for the recently opened CCI, one wonders whom Lester Graham envisioned as the typical clientele. Roadside-restaurants, according to Jakle, aimed to attract more “affluent customers motoring out for pleasure from cities and towns,” seeking “dining experiences removed from the ordinary.”26 The _Seattle Times_ advertisement did, as Jakle contends, cater to white middle and upper class customers with “discriminating palate[s]” and enough money to frequent the theatre, host parties (complete with fried chicken), and appreciate a cuisine “in a class by itself.” Its presence in the Seattle Times, a paper with citywide distribution, also suggests Graham was reaching out to many different white neighborhoods in Seattle.27

But while the CCI tried to paint itself as a restaurant “head and shoulders above the average,” the real composition of the clientele remains in question. Paul de Barros describes the CCI as a local college hangout where students went to hear live music at Club Cotton, a venue able to accommodate more than 250 people that opened in 1934, located around the corner and down the stairs from the CCI.28 Hattie Horrock also mentions the CCI as being very popular, especially with young people.29 At least one group of college students went there: a menu found in a college scrapbook that belonged to a woman who graduated from the University of Washington in 1945 has the words, “Barn Dances, Chicken Dinners, Fun” scribbled on its interior.30

Born in February 1930, just months before the CCI opened its doors, Seattle native Jean Stewart recalls growing up a mere three blocks south of the CCI. She describes the restaurant as a “lower class place” and one that would have been “racy” to go to.31Stewart grew up in a newly developed neighborhood, her house built in 1928 with her father being the original owner. The neighborhood was upper middle class, even through the Depression years, and Stewart adds that it was “extremely class conscious.” Drawing a very distinct line between Lake City and her own neighborhood, Stewart describes why her family never talked about eating at the CCI if they did go:

“You didn’t go up there. You went to the University District. Pretty racy to go there … we didn’t go there often because it was a lower class place. It was simply people who … you see, we were very class conscious … you never took a step down, particularly with my German grandfather. It was very tight, very uncomfortable living … the pressure of all these small things was just too much. You always had to be proper, trying harder … it was very structured.”32

Whether or not Stewart was merely ultra-sensitive to the social strata, her description of the CCI makes one thing abundantly clear: discussing the offensiveness of the Coon logo seemed a low priority when comparing it to white class issues.

This indifference to the racist nature of the CCI in favor of class concerns becomes even more evident when one considers a joint labor protest against the CCI by the Bartenders, Cooks, Waiters, and Waitresses Union (BCWW) and the Musicians Union that took place in March of 1937. The unions picketed the CCI for a week, protesting against the unfair treatment of organized labor and demanding that the CCI be completely unionized. On March 18th, E. B. Fish, the labor counsel for the Seattle Chamber of Commerce labor relations department; Jack Weinberger, the international representative of the BCWW; and Lester Graham signed the standard agreement of the unions.33 The _Times_ report of the agreement makes no mention of the bigoted logo. A photograph of the protest, published in the _Seattle Post Intelligencer_ with the caption, “Big Crowd, Little Profit,” captures a large crowd of white males standing in front of the giant Coon head. The men are holding picketing signs with the word “Unfair” written in bold while the Coon-head winks in the background, as if covertly communicating that he understands the irony of this photograph.34

These demonstrations of apathy and indifference towards the racial dimension of the CCI leave the question of why it seemed to resonate with Seattleites for 20 years. The Coon image appeared on every dish, silverware, menu, matchbox (the image even appeared on the matchsticks), and children ‘fans’ produced for the restaurant. The giant Coon face greeted customers as they entered the restaurant, spat them out when they left, or just gaped with its giant red lips at motorists on the Old Bothell Highway. Inside the restaurant, patrons were welcome to consume the “Southern Fried Coon Chicken”, the “Baby Coon Special” (complete with crisp French fries, hot buttered Parkerhouse Rolls, an olive, and a pickle), or the “Coon Fried Steak.”35 Down the road, one could visit the Associated Poultry Co., which proudly advertised its role in supplying the CCI (the poultry store was conveniently owned by Graham).36Or, one was welcome to frequent Club Cotton and dance next to a Coon cutout while listening to the all-white Johnny Maxon’s Orchestra.37

The abundance of Coon-related imagery—from drinking glasses to fried chicken specials to matchsticks—was but another manifestation of the racism that reinforced white supremacy in an increasingly diverse and modernizing city. Although surely the success of The CCI is attributable to more than just the memorable logo, the image was a blatantly visible declaration of bigotry in North Seattle—in its own inimitable way, it echoed the restrictive covenants and other discriminatory measures in the wink of its twinkling black eye. The historical Coon image was revived and, not surprisingly, adapted to fit the needs of the community it served: the Coon of the CCI was both the dandy and the chicken lover, but this particular Coon took on a new characteristic. He was well behaved and content to be servile. This Coon was not stealing chickens or merely lazing about, and although he dressed in nice clothing much like a dandy, the CCI Coon was a waiter through and through. 38 This representation of blacks being contented in their place in society reveals the deep-seated fear of upheaval and change that helped fuel the development and popularity of the CCI logo, which in turn reaffirmed the existing racial discrimination and bigotry.

Though the CCI does not appear in newspapers in the 1940s, the restaurant persisted on the Old Bothell Highway until late 1949, when Lester Graham removed the Coon head from public view and closed the restaurant’s doors. But neither Graham nor the CCI disappeared from Seattle completely. In December 1949, the _Lake City Citizen_ featured an advertisement for the newly opened G.I. Joe’s New Country Store, giving its location as the old Coon Chicken Inn building (Lester Graham owned the Country Store).39 This advertisement demonstrates that even after the CCI closed, the Coon-face remained a landmark for years to come. As there is no evidence that Graham closed the CCI due to protests or objections to the name, logo, or method of advertising, one can only speculate the reason the CCI’s days ended.

The coming of World War II in Seattle brought with it a surge of African-American migration, increasing the black population in Seattle from 3,789 to 15,666, or 413 percent between 1940 and 1950.40 Finding limited employment opportunities at such companies as Boeing and experiencing blatant acts of discrimination, many African-Americans campaigned for equal employment and desegregation. In 1949, the Fair Employment Practices law was passed and in 1948, racial restrictive covenants were declared no longer enforceable by the United States Supreme Court. Perhaps this change in the racial landscape of Seattle and the nation made hostile images like the Coon increasingly unpopular. Another possibility is that the migration of young white families to Lake City after World War II affected the out-of-town dining experience that early CCI customers seem to have found appealing in the CCI. Perhaps it is a combination of these factors. As the city progressed and expanded, Graham may have found the G.I. Joe’s Country Store to be a more modern and profitable venture than the chicken-restaurant enterprise.

Today the original CCI building is gone. A succession of restaurants have occupied the property near 18th NE and NE 85th Street where the Coon-head once grinned, where the Baby Coon Special was served, and where the Johnny Maxon Orchestra once played to enthusiastic all-white audiences. Though it is gone, the Coon Chicken Inn should not be forgotten. It offers a window into understanding the racial climate of Seattle during the 1930s and 1940s; the popularity of its caricatured logo helps us make sense of the white hostility and oppression harbored against African-Americans as well as allows us to see how African-Americans reacted defiantly to that oppression. Furthermore, the Coon Chicken Inn is a way to measure the progress Seattle has made over the past sixty years in terms of racial equality—and to envision the progress yet to be made.

**Copyright © Catherine Roth 2009

**HSTAA 498 Fall 2008

1 MacIntosh, Heather. “Staton, Joseph Isom: An Oral History.“ HistoryLink. 4 Nov. 2008 <http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=2431>

2 Oxford English Dictionary

3 Strausbaugh, John. Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult & Imitation in American Popular Culture (New York: Penguin, 2006). An alternate explanation for the origin of the term “coon” comes out of the transatlantic slave trade. As captured Africans awaited loading onto the slave ships that carried them on the Middle Passage to Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America they were held in makeshift pens called “barracoons.”

4 Ibid

5 Ibid, 95

6 Goings, Kenneth W. Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Stereotyping (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994).

7 Williams-Forson, Psyche A. Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 48

8 Ibid

9 “‘Coon Cards’: Racist Postcards Have Become Collectors’ Items,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, No. 25 (Autumn 1999), 72.

10 Ibid.

11 “Coon Chicken Inn Opened in Seattle,“ The Seattle Times, 31 Aug. 1930: 13.

12 “Restrictive Covenant Database.” The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. Last accessed 7 Dec. 2008 covenants.htm

13 Horrocks, Mrs. Hattie Graham, Restaurants of Seattle, 1853-1960

14 Soda Fountain Magazine, as quoted in John A. Jakle, Fast Food: Roadside Restaurants in the Automobile Age (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2002), 44.

15 “Coon Chicken Inn Opened in Seattle,“ The Seattle Times 31 Aug. 1930: 13.

16 Ibid.

17 Davidson English, Arline, “Coon Chicken Inn to Change Advertising,“ Northwest Enterprise 25 Sep. 1930: 8.

18 Taylor, Quintard, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 81

19 Staton Interview.

20 Davidson English, Arline, “Citizens Protest Against ‘Coon’ Chicken Inn,“ Northwest Enterprise 18 Sep. 1930: 8.

21 Taylor, Forging, 80; NW Enterprise December 11, 1930

22 The NW Enterprise, Sep. 25, 1930

23 McIver, Sadie, “Files Protest Against ‘Coon Chicken’ Advertisement,” Northwest Enterprise July 16, 1931: 8.

24 Black, Candace, “Chicken Inn Dodges Suit with Blue Paint,“ Northwest Enterprise 17 Mar. 1932: 6.

25 Taylor, Forging, Appendix.

26 Jakle, Fast Food, 49.

27 Advertisement, The Seattle Times, August 1930.

28 Club Cotton Advertisement in possession of the Shoreline Historical Museum.

29 Horrocks, 50

30 Menu in possession of the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project

31 Personal Interview with Jean Stewart, Nov. 8, 2008.

32 Stewart Interview.

33 “C. of C. Helps to End Dispute,“ The Seattle Times 18 Mar. 1937.

34 “Big Crowd - Little Profit!“ Seattle Post-Intelligencer 8 Mar. 1937.

35 Menu in possession of the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

36 Photograph of the Associated Poultry Co. in possession of the Shoreline Historical Museum.

37 De Barros, Paul. Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 1993).

38 Stewart Interview; “Big Crowd - Little Profit!”

39 “Joe’s Country Store,” Lake City Citizen, December 8, 1949

40 Taylor, Forging, 136.