Equality of rights and responsibility under the law shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex.(Washington Constitution, ARTICLE XXXI,Sec.1, 1972)

The Equal Rights Amendment was first introduced on the floor of the U.S. Congress in 1923 when suffragist Alice Paul of the National Women's Party proposed the measure after successful passage of the 19th Amendment.[2] Over the next forty years, the ERA, as it became popularly known, was introduced in every session of Congress until 1971 when Rep. Martha Griffiths dragged the amendment out of the House Judiciary Committee onto the floor of the House of Representatives where it was passed on October 12.[3] Five months later, the US Senate approved the ERA by a vote of 84-8 and began the process of sending the amendment to the states for ratification. For an amendment to be ratified three quarters of state legislatures, or 38 states, must vote in its favor. On the day the ERA passed the Senate, March 22, 1972, Hawaii was the very first state to pass and ratify the ERA that same day.[4]

Washington state, however, took a more deliberate and intensive approach, and did not ratify the federal ERA until a full year later, on March 22, 1973, becoming the 30th state to do so. There was purpose behind the delay. Washington ERA supporters planned to fortify the federal ERA with a state version of the Equal Rights in the Washington State Constitution.

During that year, fierce battles raged in state after state as pro-ERA groups and anti-ERA groups fought for media attention and the support of legislators and other public officials. The National Organization for Women was the best known of the many women's groups supporting the ERA. Phyllis Schlafly's STOP ERA tried to coordinate the opposition. In Washington state the battle lines were similar but also reflected the unique political alignments of the state and the fact that two decisions were at stake, whether the legislature should ratify the federal amendment and whether Washington needed its own constitutional amendment.

This essay examines the context of national politics, state government, and the actions of local politicians, organizers, and activists that enabled the passage of both the state and federal ERA in Washington, ultimately showing how the movement for equal rights increased visibility of women's issues in politics and of women themselves.

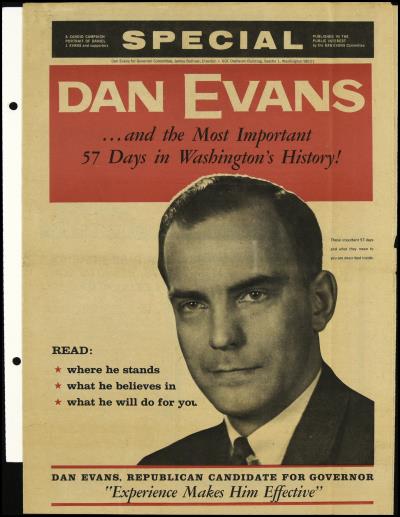

Legislative Initiative and the Women's Council

Republican Governor Dan Evans was an early and important supporter of the ERA. In preparation for the January 1972 legislative session, Evans commissioned the Washington State Women's Council in late 1971, citing "the rapid rate of change occurring today... is having a pronounced impact on the role of women in our society."[5] The fifteen council appointments focused on diversity and experience, and included chair Anne Winchester of the State Council on Higher Education and Gisela Taber as executive director, as well as Mrs. Sue Tomita of the Japanese American Citizens League, Mrs. Ramona Morris from the Lummi Tribe in Bellingham, attorney Betty Fletcher of the Seattle-King County Bar Association, EEOC Commission investigator Lynn Bruner, Mrs. Albert Green Jr., Annalee Carhart of Spokane, Shirley Charnell of Federal Way, Dr. Inga Kelly of Pullman, Mrs. Waneta McClung of Longview, and State Rep. Lorraine Wojahn of Tacoma.[6] These women were already involved in local women's organizations such as the League of Women Voters, and became vocal and strong supporters of the ERA.

The Women's Council and its members would prove key to public and governmental support for the state amendment. Soon after the council was formed, they began drafting two major pieces of legislation to be introduced in the January legislative session, one of which was the state equal rights amendment which became House Joint Resolution 61. Secondly, they drafted a community property management bill to benefit married women.[7] This early drafting of a state measure, even before the federal ERA was brought out of Congressional committee, acted as a safeguard that would make changes in the state with or without federal ratification.

The council became a major lobbying force for their legislation, announcing publicly that equal-rights legislation was their top priority.[8] By targeting equal rights through two specific bills, the council had mobilized unanimously behind a clear, realistic goal that was communicated to the legislature.

The Women's Council was aided by several other women's groups who came out in force that January, creating "more political pressure than ever before." One day, over 200 women filled the state legislature to speak to their representatives. [9] They came from groups including the Washington State Women's Political Caucus, Washington Women Lawyers, and local chapters of the American Association of University Women and NOW, and lobbied on behalf of the ERA amendment and more comprehensive bills pertaining to women, including the community property bill and divorce-law reform.[10]

The amendment, once drafted, was sponsored by Rep. Lois North of Seattle and introduced in the state House on January 1, 1972. North, a Republican and one of seven women serving in the state legislature at the time, stated that both parties "can't just give lip service to the equal-rights amendment and elimination of sex discrimination. They have to take an active, not a passive, part in recruiting women" to the legislature.[11] The state ERA bill (House Joint Resolution 61) passed the House on February 5, 1972 by a vote of 96-3.[12]

The bill faced opposition from both parties in the all-male Senate where a group of Eastern Washington senators, led by Sen. Jack Metcalf of Mukilteo voiced strong objections questioning the necessity of the amendment.[14]While there was a delay due this hesitation, the ERA did pass 36-13 as Senate Joint Resolution 106 on February 11, 1972, with 7 Democrats and 6 Republicans voting against the measure. This was one month before the Federal Constitutional Amendment cleared the U.S. Senate.[15]

Passage of the state ERA in the legislature did not mean the work was over; indeed, it had just begun. Constitutional amendments need to be approved by the voters in Washington State. Legislative approval meant that the amendment would appear on the November ballot as a referendum. A nine month campaign and a vote of the electorate would decide the fate of the proposed amendment. As a critical opening step in the campaign, the Governor and several state agencies endorsed the resolution and would continue to monitor the measure through its campaign. As important as this was, it would fall to the women in the state to organize and campaign for Washington's ERA.

Governor Dan Evans

Governor Evans publicized his endorsement of the measure from its launch and continued to be a vocal supporter of women's rights throughout the campaign.[16] In late August, two and half months before the election, Evans declared a Woman's Day and Women's Week in support of raising awareness for HJR 61.[17] This Woman's Day fell on the 50th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, and the symbolism encouraged groups like the Pierce County pro-ERA organization to spread awareness about the amendment in their community.[18] The governor took additional steps on behalf of the amendment as the campaigns for and against heated up, braving the controversy by speaking on behalf of working women and those "constantly striving to serve their communities, their states and their nation in civic and cultural programs."[19]

Years later, Governor Evans spoke of his motivation to back the amendment while mentioning a related issue, his effort to find women to appoint to state judgeships. "I did some research and found out that 20 years earlier, the graduations of the law schools in Washington were 99 men and one woman or the year after it was 100 men and no women," Evans said in an interview with the author. "If there were no women in the graduating classes, there couldn't be any selection" of women for prime appointments, as at the time the few women in the legal field primarily worked as secretaries and did not attend law school.[20]

Evans viewed the ERA as a tool to expand opportunities in education and employment for women, citing "clearly quite open discrimination against women when they [were] in competition with men for any kind of responsible job." He saw his efforts as far from radical. He simply wanted to find a way for women to get in the door, to claim equal opportunities. Prior to the introduction of the ERA in the legislature, the governor, a Republican, had signed historic abortion law reform into state law in 1970, among his efforts to "expand rights, not to restrict them." Now, the time was ripe for another legislative reform for women's rights.

The governor invested full support behind efforts to ratify the state and federal amendment. "We wanted it to be just as good as [it] could be at the state level,"[21] he said. The willingness to do so spoke to the strength and necessity of the measure, and the governor's support was instrumental to the organization of the campaign.

Women's Groups

The architects of the state ERA launched two committees to kickstart the work: the ERA Campaign Committee, including State Reps Peggy Maxie and Lois North,[22] and the Committee for House Joint Resolution 61, chaired by Dr. Glenn Terrell, president of Washington State University, and Betty Fletcher of the Women's Council.[23]

But the movement was much broader. The campaign for an equal rights amendment won support from women's groups across the state, who publicly endorsed HJR 61 in newspaper "Vote Yes" ads, including the American Association of University Women, ACLU-Washington, Common Cause, King County Council, League of Women Voters of Washington State, the state NOW Chapter, the Pacific Northwest Chapter of Sierra Club, Seattle Branch of the NAACP, the Seattle-King County Bar Association, Seattle-King County YWCA, Seattle-Tacoma Newspaper Guild, Seattle Women's Commission, Washington State Democratic Party, Young Democrats, Washington State Federation of Republican Women, Washington State Women's Political Caucus, and Young Republicans of King County.[24] These groups held information meetings, rallies, and debates as the campaign progressed, and provided an opportunity for women to gather and build a personal connection to the cause. For these women, political momentum was in their favor.

The state ERA was highlighted in local newspapers, often with coverage authored by female reporters. Susan Paynter, a young reporter for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, authored a twelve-part "Equal Rights" series, with articles exploring "A 50-Year Struggle for Equal Rights", to "Military Draft: Is It Just a Man's Burden?", "Protection: A Woman's Liability?" to name a few. Paynter's coverage included an analysis of women's place in society, examining challenges women faced in employment, labor, education, and families.[25] In some articles, she predicted legal changes ratification of the ERA would bring about; anticipating, for example, an overhaul of child support law and the elimination of mandatory exemptions of women from serving on juries.[26] Her articles were not entirely pro-ERA. She also wrote about the opposition and their arguments.

Other notable female reporters on the issue included Sally Gene Mahoney and Marcia Schultz of the Seattle Times, Barbara Anderson from the Tacoma News Tribune, and Lorrie Temple of the Post-Intelligencer. Newspaper readers were motivated to take part in the debate and write in their opinions, whether supportive or critical of the amendment and its coverage.[27] Some readers questioned the placement of ERA coverage women's lifestyle sections of various newspapers instead of the front pages. Marjorie Stern of the Women's Rights Committee commented in the Post-Intelligencer that "Would that they were placed in another section of the newspaper not segregated for women, so that they could be read by more men, for they have to be informed and convinced of voting for such an amendment, too."[28] While mainly targeted at a female audience, coverage of the ERA often made headlines and informed readers of the broader issues behind the ballot measure.

Washington women and activists were also inspired by national leaders in the women's liberation movement, some of whom visited the state to campaign for federal ratification. NOW president Wilma Scott Heide spoke at a October 1972 chapter meeting in Snohomish County[29], acknowledging the fast-growing NOW organization in Washington, with thirteen chapters statewide.[30] Heide told members that the ERA's ratification was the top legislative priority and advocated further reforms including the elimination of anti-abortion laws, the study of sexism in schools, and increased rights for women in marriage and divorce law.

Organizers and campaigners worked hard for inclusivity and to forge coalitions that would ensure passage of the amendment throughout the state. This is clearly seen in the diversity of the Women's Council members themselves, with voices from the western and eastern cities, local tribes, and ethnic groups. Leaders attempted to showcase the unity of the movement across race, gender, and sexuality lines. When Gloria Steinem and Margaret Sloan visited Seattle in October 1972 to lobby for the national amendment, their unified appearance portrayed the image of a "woman's culture" inclusive of all women, including black women, lesbians, and radicals.[31]

However, this message became an organizational challenge as concerns grew over the racial and sexual diversity of the women's rights movement itself. Margaret Sloan's October appearance at an event held by the Seattle-King County Bar Association prompted her to, as reported, "ask that gathering of young lawyers where they hid the black community" not represented in the audience.[32] And Sloan was not alone. The reputation of the Seattle Women's Commission was shaken by charges of "overt racism and unresponsiveness to concerns of ethnic minorities."[33] Feminist organizations like Radical Women criticized the commission as "too white and too middle class," viewing the group as out of touch with the realities of minorities and working women.[34] The efforts to build coalitions in favor of equal rights provoked many to push for increased rights and representation within the women's movement itself.

"Equal Rights: Plot Against Christian Family?"[35]

However, as it was nationwide, in Washington state the ERA did not appeal to all women and voters as conservative values and arguments quickly surfaced in the state. As the women's liberation movement became prominent and the campaign for equal rights amendments advanced, conservative women, traditionally less politically active, felt threatened and formed an active and effective opposition.[36]

Groups against HJR 61 did not coalesce as quickly or effectively as those in favor did but came out in force during the summer of 1972 as the election loomed. Similar to Schlafly's solo leadership on the national stage, in Washington state, one woman, Mrs. Robert Young, emerged as a critical voice. Young saw HJR 61 as anti-family and pro-communist, organizing a group called Happiness of Motherhood Eternal (HOME). This later changed to Happiness of Womanhood (HOW), and Young also led the League of Housewives modeled after the League of Women Voters.[37]

Anti-ERA groups took on religious rhetoric that allowed them to build a coalition of housewives and suburban and rural households. At a debate, Young stated: "Women's libber's aren't Christians. We believe the wife and the mother is on a pedestal. Why should she descend to equality?"[38] Resistance to the measure was strongest outside of Seattle as hotspots of opposition formed in Bellevue and Pierce County, far from the city activists. According to the Seattle PI, it was common for some husbands to tell their wives to "vote his way... or else." [39] Anti-Era activists organized their opposition in similar ways to the campaign for ratification, relying on local and national leaders. They also relied on local church leaders. Several Baptist ministers in Bellevue and Pierce County issued statements against women's liberation, such as "A vote for the ERA is a vote against God."[40] In July 1972, National Happiness of Womanhood (HOW), leader Jaquie Davison spoke at an anti-ERA conference in Bellevue to denounce women's liberation, targeting concerns that "We don't want our young girls taught that there's no joy in being a wife and mother."[41]

Opponents mounted other arguments against HJR 61, some of them designed to scare voters. HOME claimed the amendment would legalize same-sex marriage and eliminate gendered restrooms. They stressed that elimination of gender specific laws would harm women, claiming that mothers would lose custody of their children and lose protective labor legislation.[42] Arguments further targeted families by claiming the ERA would cause an overwhelming "decline in morals and cause an increase in alcoholism, divorce, desertion and sexual deviation"[43] if women were to go to work instead of stay with their children. These fears forced women's rights advocates on the defensive, forcing them to clarify that, while the ERA would eliminate sex differences in the law, the amendment would not legalize rape and other laws based on physical differences.[44]

ERA and the Draft

The idea that the ERA's passage would make women eligible for the draft incited the most fear among voters. Nationally, as well as in Washington state, the image of daughters going off to war angered many women into vocal opposition, spreading fears of female draftees sharing restrooms and living quarters with men.[45] Controversy over the draft hindered the state campaign even though the amendment, a state measure, would not in any way affect the draft eligibility of women. But it remained a powerful strategy for conservatives who continued to emphasize the military draft, leading many voters to opposition under the belief that the legislature would base ratification of the federal ERA off of HJR 61's success.

The draft was a tricky issue for ERA supporters. Many liberal supporters argued for the abolition of the draft itself for both men and women, linked to the antiwar movement. One ERA supporter, Judith Deeter, wrote to the News Tribune stating "it would seem more prudent [to] spend more time and energy working to abolish the draft altogether than working to deprive one half of humanity of its equal rights."[46] However, some supporters also lobbied for equality within the military itself and a woman's right to enlist and fight if she wished. Richard Marquartis, state director of the Selective Service in Washington, endorsed both the ERA and the draft, speaking of the career opportunities service could afford. "We're denying women the benefits men get, learning a craft or trade skill just as men do, giving them experience in areas where they've never been trained before,"[47] Marquartis said. Liberationists simultaneously argued both for the structural abolition of the draft and the need to increase female representation in the military in the meantime. This argument may have been clouded by its complexities and the strength of the fears conservative activists played on, despite assurances that the army would turn all-volunteer by the time the ERA took effect. Certainly, by the time HJR 61 reached the ballot box, fears of female draftees had not been completely allayed.

Voter's Pamphlet Controversy and the Election

The voter's pamphlet that was printed for the Nov 7 election is the clearest example of the issues crucial to the two campaigns. Statements were printed by the office of the Secretary of State, A. Ludlow Kraemer in a neutral and nonpartisan manner.[48] Designed to be informative to voters, conflict quickly arose as the pro and anti ERA groups took issue with the other's statements.

The statement against HJR 61 was written by Sen. Jack Metcalf and Dennis Dunn, King County Republican chairman.[49]Their overarching argument was that "HJR 61 is a constitutional amendment requiring that NO distinction be made between men and women."[50] They followed with a list of unfavorable changes they claimed would occur: including women losing preferential insurance rates, losing gender specific sports teams, the legalization of same sex marriage, loss of deferential child custody, and the drafting of women in the military.

After the pamphlet was printed in early October, ERA proponents fought back these statements. Betty Fletcher of the Equal Rights Amendment Committee called the allegations that the law would make no difference between men and women "simply untrue", and publicity head Ernesta Barnes attacked the factual basis of the claims, calling the issue of same-sex marriage an "irresponsible fantasy" and questioning if women were really treated preferentially at the time.[51] The statement in favor of HJR 61 printed in the pamphlet followed these beliefs, explaining that the amendment would lead "both sexes [to] be treated equally under the law", and discerning myths that it would disrupt private family life.[52]

As the two groups publicly disputed each other's claims, the election was approaching. Mrs. Young of the Committee to Stop ERA criticized the Secretary of State's office for answering phone calls requesting additional information on the ERA, calling their actions "propaganda"[53] and biased towards support for the measure.

On the eve of the Nov 7 election, HJR 61 remained an "emotional" issue for many voters, both for supporters and opponents who were either hopeful or fearful of its passage. Many women linked the ERA to the origins of the women's rights movement and the 19th Amendment that had granted them the right to vote in the first place, tracing back a 50-year struggle for equality. One woman, in a letter published to the Tacoma News Tribune, remarked "I will take my full two minutes of privacy in casting my ballot" to "pulling the 'yes' tab for the Equal Rights Amendment ... My mom will be proud of me."[54] Many opponents wrote letters registering concerns of their statuses as mothers being threatened, sometimes mocking supporters as "career women"[55] who chose work over family. Most letters were in favor of the measure, as was the bulk of news coverage. This included the normally conservative Seattle Times with an editorial endorsement coming from the Seattle Times anticipating changes HJR 61 would bring.[56]

On election day, however, it initially appeared that the campaign had failed. On November 8, the day after the polling, the Seattle Times published the headline "Equal rights measure heading for defeat" with yes votes trailing by 10,000.[57] Reporters started analyzing what might have caused such a loss, with headlines such as "Emotionalism hurt the ERA"[58] and "Tears Shed for HJR 61."[59] Young and the HOW/League of Housewives saw it as a success against the odds.[60] Both sides blamed the voter's pamphlet for presenting misleading information and the issue-based campaign that was tied up in national politics.[61] With the vote so close, certification of the results came down to the counting of mailed absentee ballots.

As these ballots were counted, the story changed. The cliffhanger absentee vote was ultimately enough to secure passage of HJR 61, passing by a slim margin of 3,369 votes and a 50.13% majority out of 645,115 votes cast.

Voters in King County carried the amendment to success by a margin of 40,000 extra votes to make up those lost in more rural areas of the state.[62] Ultimately, the amendment won in 15 counties and lost in 21, with Pierce and Snohomish counties owning the largest margin of votes against it. A UW poll found that among the 'no' votes, men disfavored the measure 2 to 1, with support polling strongest among white progressives and weaker among other minorities.[63] Ironically, a study conducted by Washington State University sociologists found that of 800 random residents surveyed, a higher proportion of male voters were likely to support the measure than of women, as the female voters were split between the two opposing campaigns. The study found that the qualities of being poorly educated, unemployed and married increased the likelihood of voting against the amendment for female voters. [64]

Votes Washington HJR 61 (1972 election)

-

| Results | YES | NO |

| Numbers | 645,115 | 641,746 |

| Percent | 50.13% | 49.87% |

Aftermath and Federal Ratification

The election, although a hard fight, was ultimately a victory for the Governor and women's groups. "I'm very pleased, and I think that the closeness of the vote added to the feeling of reward that we all feel," said Dr.Glen Terreal of the State Equal Rights Campaign Committee. [66]

HJR 61 was adopted as Article XXXI to the Washington State Constitution on January 9, 1972.[67]The work of the legislature then focused on implementing it. Adoption of the amendment was accompanied by an omnibus bill in the legislature after a review of statutes showed that over 130 laws would be affected.[68] This omnibus bill, drafted by the Women's Council, mostly made minor changes such as making the terms "woman" or "man" gender neutral. However, after it passed the legislature Governor Evans vetoed technical portions of the bill that were in conflict with other legislative bills.[69]

The 1973 legislature also passed several bills changing marriage and divorce laws and prohibiting sex discrimination in credit and insurance, actions prompted by the Women's Council's initiatives. Assistant Attorney General Gayle Berry and Seattle Women's Commissioner Jackie Griswold pushed women's legislation further, considering comprehensive changes in state rape laws and changing prostitution laws to include males as well as females.[70] Rape laws in the state were soon overhauled in 1975, eliminating long-lasting gender-based bias in the law.[71]

Ratification of the federal ERA after the passage of HJR 61 ran relatively smoothly and did not seem to be jeopardized by its narrow victory after the November elections as some had predicted or feared. Governor Evans announced his intent to ratify the ERA in his state address opening the January 1973 session.[72] The state legislature held hearings early February in front of the House and Senate Constitution and Election Committees.[73] Several prominent legal experts, including Professor Cornelius Peck of the University of Washington Law School, King County Superior Court Judge Janice Niemi, and many attorneys testified to the prevalence of sex discrimination and the necessity to pass the amendment.[74] Shortly after these hearings, the House approved House Joint Resolution 10 78-19 in favor of federal ratification and waited for its equivalent, Senate Joint Resolution 110, to pass.[75]

By this time, national political enthusiasm had faded and some thought that "women's lib may be slowing down" as only 22 of 38 states had ratified the federal amendment since March.[76] Conservative women's groups who had fought against HJR 61 tried to persuade the state legislature to reject ratification of the federal amendment, and Senator Metcalf remained an incessant voice against the amendment.[77] These objections, and an incident involving two female ERA lobbyists criticized for refusing to honor a Vietnam veteran, delayed things for a month.[78]

Ultimately the Senate Rules Committee ratified the Equal Rights Amendment on March 22, 1973, one full year after it was sent to states by the U.S. Congress. By doing so, Washington became the 30th state to ratify equal rights for women.

On the national level, ERA advocates did not prevail over conservative organizers, and the federal amendment never met its extended deadline of ratification by 38 states by 1982. However, by endorsing its own version of the amendment the state of Washington ensured that necessary legal and political changes for women would occur. Since the 1970s, twenty-five states have adopted equal rights amendments to their constitutions, with New York, Minnesota, and Maine most recently revisiting the measure in 2019.[79]

The state also saw the rise of women's voices in politics by lobbyists and activists on both sides, specifically with regards to the Women's Council. The Women's Council enjoyed great success for a few years after well-run campaigns to pass both the state and federal ERA, working to extend state protections against sex discrimination. By 1977, the state House of Representatives voted to grant the council statutory authorization as a permanent state agency, making it the Washington State Women's Commission; however, conservative opponents filed a referendum against the Council, organizing a campaign that this time was successful.[80] Even threatening to rescind the newly passed ERA, these organizers revived the "philosophical drama,"[81] as it was called by Democratic Governor Dixy Ray, over women's rights in the state. The Women's Council was dismantled by Governor Ray that same year, cementing the ERA as the most substantial achievement of the Women's Council.

"It Says What It Means and It Means What It Says"[82]

Just as debates over the ERA's legal effects dominated its electoral campaigns, so too did questions over interpretation carry over into the state's courts. The amendment first came into practice as a tool to strengthen state law, rather than one to use in individual cases. In a 1985 analysis published in the Seattle University Law Review, Patricia L. Proebsting concluded that the state was moving past sex-neutral laws to those actually anti-discriminatory in effect.[83] Unique in language for requiring both rights and responsibilities, this included the revision of statutes prohibiting sex discrimination in the selection of juries, the legal recognition of spouses, in public schools, and by employers in the payment of wages and job candidate selection. These instituted many of the legal changes that Washington women take for granted today and developed a legal culture in favor of sex-equality laws.

After the 1985 law review, courts also modified their interpretation of the amendment's language from that of strict scrutiny to an absolute standard of review for cases of sex discrimination (Washington is alone with the state of Pennsylvania in this standard). Absolute standard is two levels higher than the current federal basis of immediate scrutiny, turning the Washington State Amendment XXXI into a "powerful tool" to combat sex discrimination, according to an 2020 legal analysis at the UW School of Law.[84] In result, this has led to an interpretation banning all laws from discriminating on the basis of sex, with a few crafted legal exceptions. However, the analysis also found that in practice the ERA is only used in a slim margin of state gender-based discrimination cases, despite the high level of individual protection the amendment offers. As the courts continue to litigate gender discrimination law, the legal potential of the ERA has yet to be fully determined.

Conclusion

"I suppose the men could now complain that the Supreme Court of the State of Washington needs more men," Governor Evans said looking back and speaking on the current makeup of the court. "But I think that's just a reflection on the fact that there is a lot less discrimination now."[85]The path to equality took some time, as opportunities and rights opened to women encouraged them to pursue higher education and new careers, making their way into Supreme Court seats and other areas of prominence.

The passage of the Equal Rights Amendment granted a new expansion of rights and access to women in the state, marking a turning point in state history as sex discrimination in the law was overturned. Along with the movement it provoked, the ERA campaign revealed and extended the divisions of gender politics in the state. Ironically, both sides saw an increase in women's political authority in newspapers and public debates as women gathered, lobbied, and debated each other. The unexpected and prolonged fight and close election showed how issues including the women's place in the household, at work, and in the military related to voters, and showed a populace divided between acceptance and resistance to a rapidly changing social world in which the traditional ideals of men and women were being contested. Key to the successful passage of the amendment was the mobilization of government resources, grassroots organizations, and passionate voters, all of which transformed the legal and political environment of the state.

"The challenges change to a degree over time, but we haven't gotten to a point of such total equality that there is no challenge yet," the Governor said. "We still have plenty of challenges to create equal opportunity for men and women," but, he remarked, "I think we are far better off now."[86]

© Copyright Hope Morris 2021

HSTAA 388 Autumn 2020

[2] Mansbridge, J. (1986). Why we lost the ERA (First ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 8

[3] Mansbridge, J, p. 10

[4] Mansbridge, J., p. 12

[5] "Evans appoints council to study women's rights." Seattle Times, November 2, 1971, p. 26. Available from Readex: America's Historical Newspapers

[6] "State Women's Council Created." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 3, 1971, p. 11. Available from NewsBank: Access World News -- Historical.

[7] "Women's Group To Propose Rights Bill" Seattle Times, December 10, 1971, p. 3

[8] Mahoney, Sally Gene, "Legislation is main topic for state women's council." Seattle Daily Times, January 19, 1972, p. 28. Available from Readex: America's Historical Newspapers

[9] Bronkhost, Erin, "Women to exert more political pressure in Olympia" Seattle Times, January 9, 1972, p. 11

[10] Bronkhost, Erin, p. 11

[11] Mahoney, Sally Gene, "It's a tough row to hoe for women legislators" Seattle Times, January 16, 1972

[12] Women's rights" Seattle Times, February 6, 1972, p. 20; "Sex equality- Rights and responsibilities,"Official Voter's Pamphlet (1972), 52-53. Washington State Library. Retrieved 10 26, 2021, from https://www.sos.wa.gov/_assets/elections/voters'%20pamphlet%201972.pdf

[14] Anderson, Barbara, "Senate Places Equal Rights Issue Before Voters." Tacoma News Tribune, February 11, 1972, p.1

[15] Anderson, p.1

[16] Paynter, Susan, "Equal rights gets determined kickoff" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 6, 1972, p. 32

[17] "Woman's Day is Saturday" Tacoma News Tribune, August 22, 1972, p. 8

[18] "Woman's Day is Saturday," p. 8

[19] "Unit Pushing for Equal Rights, Tacoma News Tribune, October 16, 1972, p. 10

[20] Daniel Evans phone interview by Hope Morris, September 13, 2021

[21] Dan Evans interview, September 13, 2021

[22] Paynter, Susan, p. 32

[23] Johnsrud, Byron "Rights amendment gets male support" Seattle Times, August 18, 1972

[24] "Chapter Supports Rights Amendment" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, September 15, 1972, p. 4

[25] Paynter, Susan. "A 50-Year Struggle for Change" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 30, 1972, p. 5

[26] Paynter, Susan. "Same Penalties and Peers for Both Sexes" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 31, 1972, p. 16

[27] "The Readers Write." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 20, 1972, p. 32

[28] "Women Comment on ERA to End Discrimination" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 13, 1972, p. 18

[29] Anderson, Barbara, "Women's Group Would Liberate All People." Tacoma News Tribune, October 9, 1972, p. 12

[30] "N.O.W. preparing for its first state meeting" Seattle Times, May 7, 1972

[31] "A Lesson from Steinem" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 15, 1972, p. 36

[32] Temple, Lorrie, "Sloan Is a Good Sparring Partner." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 15, 1972, p. 35

[33] Mahoney, Sally Gene, "Heat, some light at rap session", Seattle Times, May 26, 1972

[34] Temple, Lorrie, "A Year in Seattle Women's Battle for Equal Rights." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 24, 1972, p. 3

[35] Paynter, Susan, "Equal Rights: Plot Against Christian Family?" Seattle Post Intelligencer, August 9, 1972, p. 16

[36] Mainsbridge, Why We Lost the ERA, p. 104

[37] Anderson, Barbara, "Equal Rights Amendment Draws Partisans' Views" Tacoma News Tribune, September 1, 1972, p. 8

[38] Paynter, p. 16

[39] "His and Hers" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 9, 1972, p.10

[40] Anderson, Barbara, p. 8

[41] Montgomery, Diana, "Watch Out, Women's Liberation." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 12, 1972, p. 49

[42] Anderson, Barbara, p. 8

[43] Paynter, Susan, "Equal Rights: Plot Against Christian Family?"

[44] Paynter, Susan, "Equal Rights Amendment - HJR 61 - An Emotional Issue for All" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 26, 1972, p. 4

[45] Paynter, Susan, p. 16

[46] "To the Editor" Tacoma News Tribune, April 17, 1972, p. 14

[47] Paynter, Susan, "Military Draft: Is It Just a Man's Burden?" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 2, 1972, p. 14

[48] Washington State Library. (1972). Sex equality- Rights and responsibilities. Official Voter's Pamphlet, 52-53. Retrieved 12 09, 2020, from https://www.sos.wa.gov/_assets/elections/voters'%20pamphlet%201972.pdf

[49] Mahoney, Sally Gene, and Schultz, Marcia, "Delight, disappointment in equal rights passage" Seattle Times, November 29, 1972

[50] Official Voter's Pamphlet, p. 52-53.

[51] Corsaletti, Lou, "Rights description termed 'misleading'"" The Seattle Times, October 11, 1972, p. 15

[52] Official Voter's Pamphlet, p. 52

[53] "State Misuse of Voter Line" Tacoma News Tribune, October 13, 1972, p. 4

[54] "Here's Vote for Equal Rights Amendment" Tacoma News Tribune, November 2, 1972, p. 16

[55] "Times readers have their say" Seattle Times, October 27, 1972, p. 13

[56] "Parity between the sexes" Seattle Times, October 24, 1972, p. 12

[57] Schultz, Marcia, "Equal-rights measure heading for defeat" Seattle Times, November 8, 1972, p.1

[58] Almquist, June Anderson. "Emotionalism hurt E.R.A." Seattle Times, November 12, 1972, p. 99

[59] "Tears Shed for HJR 61" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 15, 1972, p. 10

[60] Schultz, Marcia, p.1

[61] Horne, Janet, and Schultz, Marcia, "Rights vote a 'surprise'; pros hoping" Seattle Times, November 8, 1972, p.73

[62] "Equal-rights measure passes". Seattle Times, November 28, 1972, p.1

[63] Emery, Julie, "Males, minorities against H.J.R. 61", Seattle Times, November 27,1972, p. 20

[64] Gecas, V. (n.d.). The Equal Rights Amendment in Washington State: An Analysis and Interpretation of Voting Patterns. Educational Resources Information Center. Retrieved 10 14, 2021, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED160507

[65]Washington Secretary of State. Elections Search Results. Elections & Voting. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://www.sos.wa.gov/elections/results_report.aspx?e=41&c=&c2=&t=&t2=5&p=&p2=&y=1972.

[66] Mahoney, Sally Gene, and Schultz, Marcia, "Delight, disappointment in equal-rights passage," Seattle Times, November 29, 1972, p.20

[67] Mahoney, Sally Gene, "Equal Rights Amendment now officially part of Constitution" Seattle Times, January 10, 1973, p.29

[68] Washington. State Legislative Council. Judiciary Committee. (1972). The potential impact of House Joint resolution no. 61--the Equal rights amendment--on the laws of the State of Washington. Olympia: Washington State Legislative Council.

[69] "Bill Spelling Out Tax Reform Signed" Tacoma News Tribune, April 25, 1973, p. 1

[70] "State Council sets priorities for 1973 Legislature" Seattle Times, December 11, 1972, p.39

[71] Leonetti, S. (2015, 03 15). Rape and the Law: An Examination of the Relationship between Sexist Cultural Attitudes and Washington State's 1975 Rape Law Revision. Retrieved 12 12, 2020, from https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/handle/1773/33317/LRA2015_Leonetti.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[72] "Text of Evans' State of the State Address Yesterday" Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 11, 1972, p. 9

[73] Mahoney, Sally Gene, "Another round on equal rights" Seattle Times, February 8, 1973, p.23

[74] Mahoney, Sally Gene, p.23

[75] "Favorable Equal Rights Vote Tallied" Tacoma News Tribune, February 17, 1973, p. 23

[76] "The Rights' Amendment" Tacoma News Tribune, January 28, 1973, p.66

[77] Mahoney, Sally Gene, p.23

[78] Larsen, Richard W. "2 rights backers mar ex-POW fete" Seattle Times, March 22, 1973, p.66

[79] Baldez, L. (2020, 01 23). The U.S. might ratify the ERA. What would change? The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/01/23/us-might-ratify-era-what-would-change/

[80] Parry, J. (2000). Putting Feminism to a Vote: The Washington State Women's Council, 1963-78. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 91(4), 171-182.

[81] Parry, p. 178

[82] Patricia L. Proebsting, Washington's Equal Rights Amendment: It Says What It Means and It Means What It Says, 8 SEATTLE U. L. REV. 461 (1985).

[83] Proebsting, 1985

[84] Maria Y. Hodgins, State Action and Gender (In)Equality: The Untapped

Power of Washington's Equal Rights Amendment, 94 wash. l. rev. online 27 (2020), p. 40.

Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlro/vol94/iss1/2

[85] Dan Evans interview, September 13 2021.

[86] Dan Evans interview, September 13, 2021.